the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Empirical electronic polarizabilities of iodine (I−) and bromine (Br−, Br7+) for the prediction of refractive indices

Shaghayegh Nezamabadi

Patrick A. Fuzon

Florian Kraus

Reinhard X. Fischer

Empirical electronic polarizabilities of I−, Br−, and Br7+ were determined to predict refractive indices of iodides, bromides, and perbromates, respectively, at λ=589.3 nm. Polarizabilities of the iodine and bromine ions were derived from the total electronic polarizabilities of compounds containing I or Br by subtracting the polarizabilities of the remaining cations and anions, yielding the contribution of the halogen ions to the total electronic polarizabilities calculated from the mean refractive indices using the Anderson–Eggleton relationship. Refractive indices (RIs) of iodides, bromides, and perbromates are taken from literature data and from our own measurements on potassium iodide (KI), sodium iodide dihydrate (NaI ⋅ 2H2O), potassium bromide (KBr), and sodium perbromate monohydrate (NaBrO4 ⋅ H2O). Powder X-ray diffraction analyses were done for basic characterization and to check the purity. Structure analyses were performed using single-crystal X-ray diffraction data on KI, KBr, NaI ⋅ 2H2O, and NaBrO4 ⋅ H2O. Refractive indices were determined using the immersion method with a micro-refractometer spindle stage at λ=589.3 nm, yielding = 1.671(8) for isotropic KI, nx=1.585(9), ny=1.593(4), and nz=1.615(6), with a mean refractive index of =1.598(6) for NaI ⋅ 2H2O; = 1.560(2) for isotropic KBr; and nx=1.470(2), ny=1.491(2), and nz=1.492(2) with a mean refractive index of = 1.484(2) for an optically biaxial NaBrO4 ⋅ H2O crystal. The anion polarizability parameters and No for I− were determined by least-squares methods from 20 iodide compounds with known refractive indices, combined with data from this study. The electronic polarizability of the anion is described by the equation , yielding (I−) = 8.53(5) Å3 and No(I−) = 0.90 Å3.6. Similarly, for Br−, analysis of 20 bromide compounds with established refractive indices, together with data from this study, resulted in (Br−) = 5.4(3) Å3 and No(Br−) = 1.00 Å3.6. The determination of the refractive indices of NaBrO4 ⋅ H2O with four-coordinated Br7+ yielded an electronic polarizability value of 0.938 Å3 for Br7+. Using this value enables the prediction of refractive indices of perbromates. All values were validated against known halide data and used to predict refractive indices of iodine- and bromine-containing compounds. A total of 120 refractive indices was predicted. The results are compared with refractive indices calculated from Gladstone–Dale constants.

Please read the corrigendum first before continuing.

-

Notice on corrigendum

The requested paper has a corresponding corrigendum published. Please read the corrigendum first before downloading the article.

-

Article

(1239 KB)

- Corrigendum

-

Supplement

(278 KB)

-

The requested paper has a corresponding corrigendum published. Please read the corrigendum first before downloading the article.

- Article

(1239 KB) - Full-text XML

- Corrigendum

-

Supplement

(278 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

1.1 General aspects

Refractive indices are fundamental optical properties that provide critical insights into the crystal structure, composition, and bonding characteristics of minerals and synthetic compounds (Feklichev, 1992; Nesse, 2013). In mineralogical studies, refractive indices play a crucial role in identifying and classifying minerals, understanding crystal chemistry, and interpreting phase transitions (Gunter and Ribbe, 1993). Additionally, refractive indices find significant applications in laser science (Han et al., 2012). The ability to predict refractive indices allows for better characterization of natural and synthetic materials, aiding in the development of optical devices and improving the understanding of geological processes. Physically, the effect of refraction is caused by dipole moments p induced by the electromagnetic wave upon entering the crystal, which are proportional to the electric field E according to , where the polarizability α represents the factor of proportionality between the dipole moment p and the electric field E (see Shannon and Fischer, 2016, and Fischer et al., 2018, and references therein). Thus, it quantifies the extent to which an ion or compound responds to an external electric field. Dielectric polarizabilities are related to the dielectric constant by the Clausius–Mosotti relation in the range 1 kHz to 10 MHz, as discussed by Shannon (1993). Static electronic polarizabilities far below electronic resonances are described by the Lorentz–Lorenz equation for λ= ∞. For a detailed explanation of static polarizabilities, see Shannon and Fischer (2006), including extensive references to various applications. Here we use dynamic electronic polarizabilities in the visible range of light at λ=589.3 nm, as described in Sect. 1.2.1, to predict refractive indices of I- and Br-bearing compounds and minerals, extending the dataset determined by Shannon and Fischer (2016) for 270 electronic polarizabilities for 76 cations and 4 anions. Alternatively, the Gladstone–Dale relationship is applied to relate refractive indices with density and chemical composition using specific Gladstone–Dale constants from Mandarino (1981). However, this relationship does not consider the dependence of optical parameters on the coordination environment of cations (Mandarino, 1979; Bloss et al., 1983).

1.2 Theoretical background

1.2.1 Electronic polarizability

Shannon and Fischer (2006) developed an empirical approach to determine electronic polarizabilities, modifying earlier methods by analyzing refractive indices for a wide range of minerals and synthetic compounds. Their work utilized the Anderson–Eggleton (Anderson, 1975; Eggleton, 1991) relationship, which relates the refractive index to molar volume and total electronic polarizability as follows:

where αT is the total electronic polarizability of a mineral or inorganic compound, nD is the refractive index at λ=589.3 nm, Vm is the molar volume in Å3, and c=2.26 is the electron overlap factor.

Various methodologies exist for relating the refractive index (RI) to polarizability, including the Lorenz–Lorentz (LL) (Lorenz, 1880; Lorentz, 1880), Drude (see Anderson and Schreiber, 1965, and references therein), Gladstone–Dale (GD) (Gladstone and Dale, 1863), and Anderson–Eggleton (AE) models. As demonstrated by Shannon and Fischer (2016), the AE relationship offers a more accurate determination of polarizabilities from refractive indices, as it accounts for partial electron overlap, ranging between LL and GD equations. Unlike LL, which neglects electron overlap, and GD, which does not consider structural details, AE introduces a correction factor (c=2.26) that enhances the precision of polarizability estimations across a wide range of minerals. Whereas the GD and Drude approaches often lead to overestimated polarizabilities, AE provides a more refined and experimentally validated approach by incorporating electron overlap effects. Consequently, AE is generally more suitable for most minerals, though additional modifications may be necessary for highly covalent compounds, such as carbonates, nitrates, sulfates, and perchlorates.

1.2.2 Cation and anion polarizabilities

The total molar electronic polarizability (αT) of a compound can be expressed as the sum of the individual electronic polarizabilities of its constituent ions (αe(ion)) according to

where i varies over the total number (N) of ion types in the formula unit, and mi is the number of ions of type i in the formula unit. Cation polarizability is influenced by factors such as the coordination number (CN) and ionic radius, which determine the extent to which a cation can distort its electron cloud in response to an electric field. Jemmer et al. (1998) explored polarizability using a light-scattering (LS) model, showing that polarizability systematically decreases as the coordination number (CN) increases. Shannon and Fischer (2016) give a detailed explanation of this approach. Anion polarizabilities depend on the volume occupied by the anion corresponding to the volume of the unit cell divided by the number of anions. Shannon and Fischer expressed anion polarizability (α−) as

where is the free ion polarizability, Van is the anion molar volume, and n=1.20 is an empirical parameter. The refractive index can then be calculated solving Eq. (1) for n according to

1.2.3 Refractive indices and total polarizability calculated from Gladstone–Dale approach

Alternatively, the mean refractive index could be calculated from the Gladstone–Dale approach (Gladstone and Dale, 1863) using a set of parameters ki (Gladstone–Dale constants), determined for the oxide components in a mineral or inorganic compound by Mandarino (1976, 1981), according to

where pi is the weight percentage of the oxide component i, and D is the density of the compound. The treatment of halide components is explained by Fischer et al. (2018) and in the examples on p. 74 in Mandarino (1979).

The total polarizability using the Gladstone–Dale relationship is expressed as

with the molar volume Vm and the refractive index n (see Shannon and Fischer, 2016).

Whereas this method has been widely used for mineralogical studies, Shannon and Fischer (2016) found that it shows larger discrepancies compared to the Anderson–Eggleton approach.

The Gladstone–Dale compatibility index CI measures the consistency of refractive index, density, and chemical composition by comparing a specific chemical refractivity,

to an experimental physically derived value , where ki is the Gladstone–Dale constant, pi is the weight percentage, and D is the density (Mandarino 1979, 1981). However, its reliability is affected by structure-dependent variations in ki values, as pointed out by Bloss et al. (1983).

Eggleton (1991) revised ki values for various cations, improving the agreement of CI calculations, with high agreement in most cases but still with larger error margins compared to polarizability analysis.

1.3 Focus of this work

Whereas Shannon and Fischer (2006) extensively covered oxides, fluorides, chlorides, and hydroxides, their study did not comprehensively address the polarizabilities of iodine (I) and bromine (Br) atoms in different oxidation states. Given the importance of these halogens in both natural and synthetic systems, further refinement of their empirical polarizabilities is necessary for accurate refractive index predictions in compounds containing I or Br.

Notably, Shannon and Fischer (2016) calculated the electronic polarizability value for I7+, which is adopted in this study for refractive index predictions of I7+-containing compounds. However, the polarizabilities of I−, Br−, and Br7+ have not been determined previously and are derived in this study to improve the accuracy of refractive index predictions for iodine- and bromine-bearing materials. The bromine electronic polarizability values were initially derived in the master's thesis of Nezamabadi (2023). In the present study, these values have been improved through additional computational and experimental validation to ensure greater accuracy and broader applicability. Additionally, I5+ and Br5+ are investigated in this study; however, due to the presence of lone-pair electrons, their behavior deviates from the usual trends. The resulting discrepancies are currently under investigation. I3+ and Br3+ are not included in this study due to their inherent instability and strong tendency to convert into more stable oxidation states.

Previous work has focused primarily on the electronic polarizabilities of fluorine (F−), chlorine (Cl−), and hydroxyl (OH−), with well-documented values derived from experimental and computational studies. However, data on iodine (I−, I5+) and bromine (Br−, Br5+, and Br7+) are missing, making it difficult to accurately predict the refractive indices of minerals and synthetic compounds containing these elements. This study employs an empirical approach based on refractive index measurements, computational modeling, and the least-squares refinement method to determine the electronic polarizabilities of iodine and bromine in different oxidation states. By applying the Anderson–Eggleton relationship and comparing results with known halide data, this work aims to find a systematic methodology for estimating refractive indices in iodine- and bromine-containing materials.

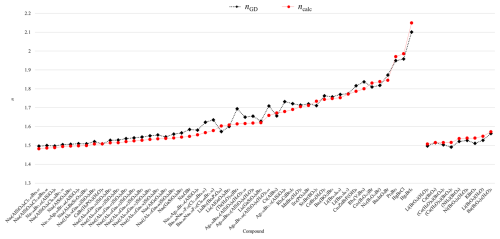

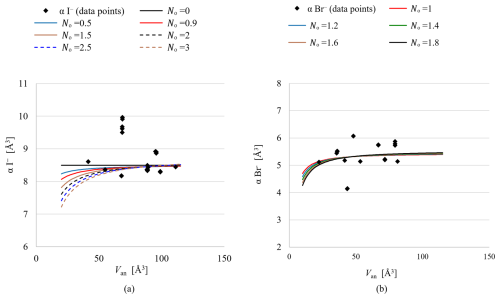

Figure 1Calculated electronic polarizability of I− in various compounds as a function of anion volume.

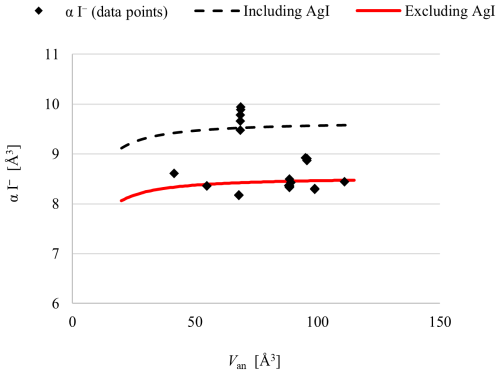

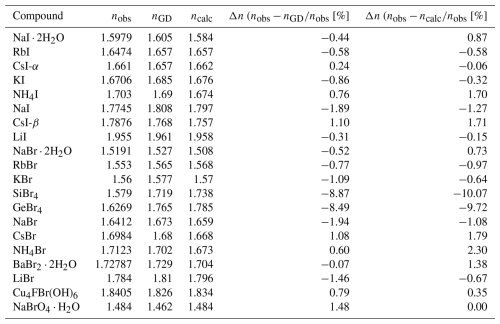

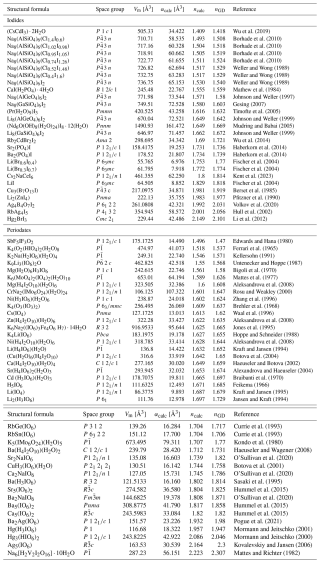

Table 2Refractive indices, molar volumes, and total observed polarizabilities used for calculating the electronic polarizabilities of I− and Br−. Data are taken from our own measurements and from literature values.

a For an explanation, see Sect. 2. b KI refractive index measured at 66 °C. c KI refractive index measured at 38 °C. d CsI-α has an NaCl structure type, and CsI-β crystallizes in a CsCl structure. e Notably, silver halides exhibit systematic behavior with relatively high refractive indices and, consequently, high total electronic polarizabilities. Therefore, they have been treated as outliers in this study. Although their data points are plotted, they are not included in the fitted data (see discussion in Sect. 3.3). f Another record for KBr shows a mean refractive index of 1.5325 (Gundelach, 1930), but it differs significantly from other values and is therefore excluded from calculations. g An additional record exists for CsBr, in which the mean refractive index is 1.5820 (Winchell and Winchell, 1931). However, this average refractive index differs considerably from the other documented values. Therefore, it is disregarded in calculations.

KI and NaI ⋅ 2H2O were selected as compounds containing iodide (I−), KBr was selected as a compound containing bromide (Br−), and NaBrO4 ⋅ H2O was selected as a compound containing bromine in its highest oxidation state (Br7+). The KI and KBr samples were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and NaI ⋅ 2H2O was obtained from Carl Roth Chemicals. NaBrO4 ⋅ H2O was synthesized following the procedure described by Appelman (1969), passing diluted fluorine gas into an aqueous, alkaline solution of sodium bromate according to the following equation:

Details of the synthesis will be reported elsewhere.

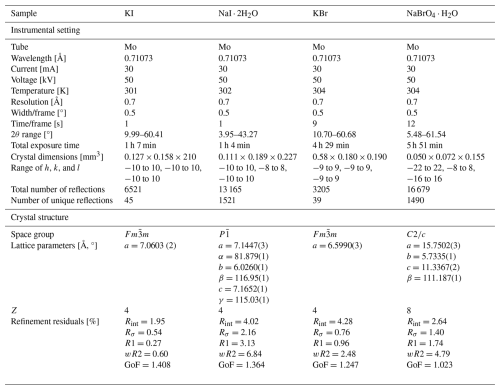

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) analyses of the NaI ⋅ 2H2O sample were done using a PANalytical X'Pert MPD Pro diffractometer, whereas the KI and KBr samples were examined with a Bruker D8 Discover diffractometer, all having a θ−2θ Bragg–Brentano geometry. Identification was carried out using HighScore analysis established by Degen et al. (2014) and Rietveld analysis with BRASS software developed by Birkenstock et al. (2006). Through PXRD analysis, mixed phases of NaI and NaI ⋅ 2H2O could be identified in the NaI ⋅ 2H2O sample, with weight percentages of 11.60 ± 0.22 % and 88.40 ± 1.23 %, respectively. This confirmed a pure phase for KI and KBr. Rietveld refinement yielded lattice parameters that are in agreement with the values reported by Verbist et al. (1970) for NaI ⋅ 2H2O, Ahtee (1969) for KI, and Subban and Dhanraj (2018) for KBr. Single-crystal diffraction (SCXRD) was performed using a Bruker D8 venture Kappa diffractometer with Mo radiation (λ=0.71073 Å) on recrystallized samples of KI, NaI ⋅ 2H2O, KBr, and NaBrO4 ⋅ H2O to confirm the defect-free crystal structure of the samples. Single crystals of each sample were obtained through slow evaporation. Data reduction and data integration were then performed using APEX4 software, and eventually, refinement of the data was done via WINGX software (Farrugia, 2012) using SHELX (Sheldrick, 2015) as the refinement program. Table 1 contains the instrumental settings for each SCXRD experiment, the crystal-structure data, and the refinement residuals. Initial atom parameters were taken from Ahtee (1969) for KI, Verbist et al. (1970) for NaI ⋅ 2H2O, Subban and Dhanraj (2018) for KBr, and Blackburn et al. (1992) for NaBrO4 ⋅ H2O. Ten least-squares cycles were carried out to obtain the final parameters. All refinement results agree with the prior findings of the above-mentioned studies. To compare the results with the corresponding parameters from the literature, the unit cell of NaI ⋅ 2H2O was transformed according to −b, a+b, and c, with an origin shift of , , and . The refined atom parameters are listed in Tables S1 to S4 in the Supplement.

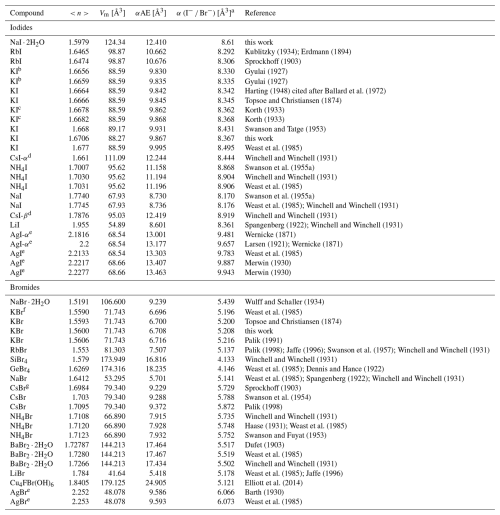

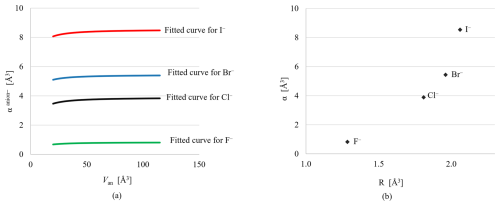

Figure 2Electronic polarizability of Br− in various compounds (listed in Table 2) plotted against their respective anion volumes.

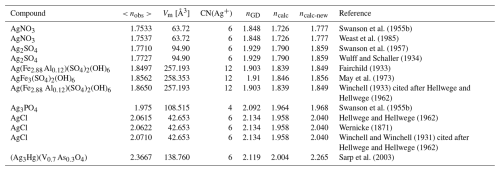

Figure 3Sensitivity analysis of No values for I− and Br−. (a) The effect of varying No on the fitted data for I−. (b) The corresponding effect for Br−.

Figure 4(a) Comparison of the fitted polarizability curves for I−, Br−, Cl−, and F− as a function of anion volume. The () values are 3.88 and 0.82 Å3 for Cl− and F−, respectively, with corresponding No values of 1.800 Å3.6 for Cl− and 3 Å3.6 for F−. (b) The relationship between the cube of ionic radii (Shannon, 1976) and electronic polarizability (α) for halogens.

The refractive index was determined using polarization microscopy with the immersion method, where the crystal was placed on a spindle stage in a liquid with a known refractive index to analyze its optical behavior through extinction patterns and the Becke method. After obtaining a match between the crystal and the liquid, the internal refractometer was used to determine the actual refractive index of the liquid, thus avoiding aging or contamination effects. The mean refractive index of each sample was determined, and the total electronic polarizability of the compound was calculated using the Polario program (Fischer et al., 2018). This program has the electronic polarizability values of each atom or ion with various coordination numbers built-in, as derived by Shannon and Fischer (2016). Using the Anderson–Eggleton approach, it calculates the total electronic polarizability of the compound from the observed refractive index. As explained in Sect. 1.2.1, the total molar electronic polarizability αT of a compound is calculated (αcalc) as a linear combination of the individual ion electronic polarizabilities (αe(ion)) according to the additivity rule (Eq. 2). Shannon and Fischer (2006, 2016) treated the ion polarizabilities (αe(ion)) as refinable parameters in a least-squares procedure that minimizes the following function:

where i represents the number of αobs measurements for different compounds, and , with σi being the estimated percentage error in the experimental refractive index. Given that each compound investigated here had only one ion with unknown electronic polarizability, multiple regression analyses were not necessary. The individual electronic polarizabilities of I−, Br−, and Br7+ were simply determined by subtracting the sum of the electronic polarizabilities of the remaining ions from the observed total electronic polarizability of the respective compound. The least-squares refinement program POLFIT, originally developed for dielectric polarizability analysis (Shannon, 1993), was modified and improved to enable the simultaneous refinement of αe(ion) for cations and anions, as well as for I− and Br−, as a function of anion volume using Eq. (3). The data required for this analysis, including refractive indices, crystal-structure parameters, unit-cell dimensions, and chemical compositions, were sourced from various references and supplemented by our findings. If the paper reporting the refractive index also included crystal-structure data, that information was used. Otherwise, the data were sourced from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) (Belsky et al., 2002). The least-squares method, implemented in the POLFIT program, was employed to determine the anion parameters of I− and Br−, as outlined in Sect. 1.2.2. Two datasets were utilized, one consisting of refractive index measurements for 20 iodides and another containing measurements for 22 bromides.

Table 3Observed refractive indices, molar volumes, and calculated refractive indices of compounds containing Ag+.

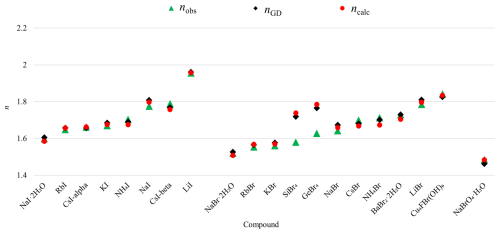

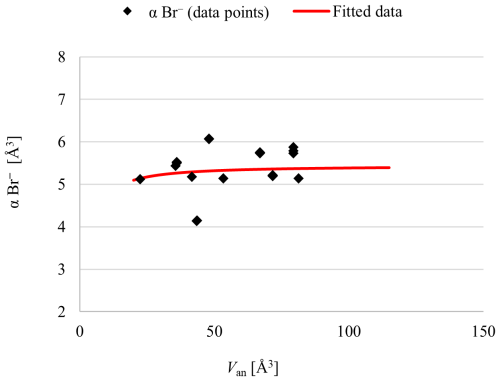

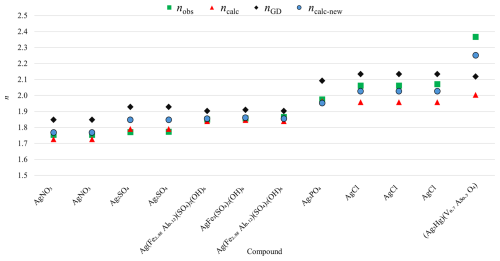

Figure 5Comparison of observed refractive index (RI) (nobs) with RI calculated after Gladstone–Dale (nGD) with values from Mandarino (1981), with polarizabilities from Shannon and Fischer (2016) (ncalc), and with mean α value calculated here (ncalc-new).

To derive the initial anion parameters for I−, a dataset of 20 refractive index measurements from 8 iodides was used. This dataset included I− and water molecules treated as anions, along with 6 cations with known polarizabilities obtained from Shannon and Fischer (2016). Similarly, the initial anion parameters for Br− were determined using a dataset of 20 refractive index measurements from 11 bromides. This dataset included Br−, F−, OH−, and water molecules treated as anions, along with 11 cations with known polarizabilities taken from Shannon and Fischer (2016). As noted in Sect. 1.2.2, the cation polarizability was determined using the polarizability additivity rule (Eq. 2). Specifically, the polarizability of I7+ was adopted from Shannon and Fischer (2006), whereas the polarizability of Br7+ was calculated based on data from a single compound.

Table 4Comparison of measured mean refractive indices with values calculated via the polarizability approach and the Gladstone–Dale method, along with their respective deviations from the experimental data.

For references, see Table 2.

3.1 Anion polarizabilities

3.1.1 Iodides

Refractive index measurements for NaI ⋅ 2H2O yielded values of nx= 1.585(9), ny=1.593(4), and nz=1.615(6), with an average value of = 1.598(6) compared to the labeled values of the corresponding oils at 1.582, 1.592, and 1.610, respectively. Verification using an internal refractometer yielded the actual refractive indices, suggesting that the discrepancies could result from factors such as aging of the immersion oil. Additionally, stepwise oil replacement during the immersion measurements may have left traces of the previous oil in the cell, leading to mixing with the new oil and a deviation in the refractive index of the resulting mixture. The optic angle with respect to the acute bisectrix in this measurement was found to be 72.8(22)°.

KI is optically isotropic. Thus, its refractive index is independent of crystal orientation. The refractive index was found to be n=1.671(8) using the internal refractometer, whereas the labeled refractive index of the matching oil was 1.664. The reported refractive index range for KI is between 1.6656 and 1.6770, as indicated by Gyulai (1927), Harting (1948), Topsoe and Christiansen (1874), Korth (1933), Swanson and Tatge (1953), and the CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics by Weast et al. (1985).

Analyses of 20 iodide compounds, including the results of this work listed in Table 2, yielded a refined value of (I−) = 8.53(5) Å3 and No(I−) fixed at 0.90 Å3.6, as explained in Sect. 3.1.3. The individual electronic polarizability of I− in the dataset is listed in Table 2. The individual electronic polarizability of the anion in compounds containing Ag+ as cation is significantly higher than in other compounds, as shown in Fig. 1. Including these entries in the least-squares analysis substantially impacts the fitted data, causing most other data points to become outliers due to a significant upward shift in the curve. Consequently, we excluded these entries from the least-squares analysis, as discussed in Sect. 3.3. Data points represent values obtained from computational refinement with numerical values listed in Table 2, and the fitted curve is derived from least-squares analysis. Notably, although data points of AgI are plotted in the graph, due to their significant deviation they have been excluded from the calculation of the fitted curve.

Table 5Predicted mean refractive indices of iodide and periodate compounds containing [4]I7+ and [6]I7+, derived from electronic polarizability calculations compared to Gladstone–Dale (GD) values.

3.1.2 Bromides

The refractive index of KBr was determined to be n=1.560(2) using the immersion method and Becke line. Analyses of 20 bromide compounds, including the results of this work listed in Table 2, yielded a refined value of (Br−) = 5.4(3) Å3 and No(Br−) fixed at 1.00 Å3.6, as explained in Sect. 3.1.3. The individual electronic polarizability of Br− in the dataset is listed in Table 2, and Fig. 2 depicts these data points and the trend line representing the fitted data obtained by least-squares analysis. Data points of AgBr are plotted in the graph, but they have been excluded from the calculation of the fitted curve. Although the electronic polarizability of bromine in AgBr compounds deviates less than that of iodine in AgI, the calculated refractive index derived from the polarizability approach ncalc=2.140 differs significantly from the observed refractive index nobs=2.252. This discrepancy indicates that silver halides require distinct treatment, and the current methodology is not yet finalized for silver halides. Consequently, AgBr compounds were also excluded from the least-squares analysis for determining the electronic polarizability of bromine.

3.1.3 Variations in and reliability of the fitted data

Due to the paucity of data points with low Van values, the refinement of the No parameter (see Eq. 3) was not stable. As shown in Fig. 3, variations in No only affect the curve at low Van, where no data points are available. Varying the value by hand demonstrates that the data points at higher Van values are not significantly influenced. Therefore, No was fixed at different values to assess its impact on the R-squared value, with a fixed value of 0.9 Å3.6 for I− and 1.0 Å3.6 for Br− yielding the best results. For instance, fixing No for I− at 0.5 yields an R-squared value of 0.96, whereas No=0.9 results in an R-squared value equal to 0.97. Although this difference is minimal, it indicates that No=0.9 provides a slightly better fit. Due to the wide distribution of data points, accurately fitting the data can be challenging, resulting in deviations between the fitted curve and the actual data points. These deviations are reflected in the spread of or variation in the data around the curve, explaining the high values for the standard deviations.

To evaluate the reliability of the fitted data, the results for I− and Br− obtained in this study were compared with fitted data for Cl− and F− from the work of Shannon and Fischer (2016). Using the same methodology, it was observed that despite notable deviations in the least-squares parameters, the curve maintained a consistent trend. Furthermore, the relationship between the cube of the ionic radii and the electronic polarizabilities of the calculated I− and Br− agrees well with the other calculated halogens and follows the same trend (see Fig. 4).

3.2 Cation polarizabilities

The measured refractive indices of NaBrO4 ⋅ H2O were nx=1.470(2), ny=1.491(2), nz=1.492(2), and = 1.484(2). The optic angle (2V) was determined to be 28(5)°. A repeated experiment with a non-recrystallized sample confirmed the consistency of these values. The final optic angle, calculated as the average from multiple measurements, was 25.2(22)°. Using α ([6]Na.560 Å3, (O2−) = 1.79 Å3, No(O2−) = 1.776 Å3.6, (H2O) = 1.620 Å3, and No(H2O) = 0.0 Å3.6, applying Eq. (2), the calculated electronic polarizability of four-coordinated Br7+ was found to be 0.938 Å3. Utilizing the relationship between electronic polarizability and refractive index, the obtained value of α(Br7+) can be used as a reference to estimate the mean refractive index of other compounds containing [4]Br7+.

3.3 Treatment of compounds containing Ag+

As indicated above, compounds containing Ag+ show significant deviations between observed and calculated total polarizabilities in halides. This can be mainly attributed to deficiencies in the initial determination of the electronic polarizability of Ag+ by Shannon and Fischer (2016). There, values for seven- and eight-coordinated Ag atoms could only be determined by least-squares interpolation between corresponding values at low and high coordination numbers (CNs), where the value for nine-coordinated Ag seems to be doubtful and consequently biased the calculation of values at lower CNs. Due to the limited dataset and potential for bias, an average polarizability value for α(Ag+) = 3.52 Å3 was used here. Table 3 lists these compounds, and Fig. 5 compares the observed refractive index (nobs), the refractive index calculated using the Gladstone–Dale relation (nGD), and the calculated refractive index (ncalc) based on the published Ag+ polarizability value (Shannon and Fischer, 2016) with a recalculated refractive index (ncalc-new) using the average α(Ag+) = 3.52 Å3. Adopting this average polarizability significantly improved agreement, with ncalc-new showing smaller deviations from nobs compared to the published value. However, to improve the accuracy of polarizability calculations for compounds containing Ag, the corresponding values at different CNs need to be redetermined.

3.4 Comparison between polarizability concept and Gladstone–Dale approach

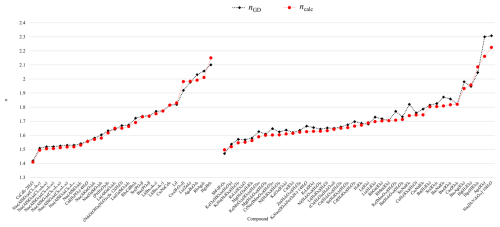

Polarizability analysis is based on empirical ion polarizabilities (αe) that are specific to ion coordination and crystal structures. The Gladstone–Dale method relates a material's mean index of refraction and density to the weight fractions of its components and to the Gladstone–Dale constants (Bloss et al., 1983). In contrast, the Anderson–Eggleton method incorporates electronic polarizability, accounting for ion coordination and electron cloud distortions, which generally improves accuracy for covalently bonded or structurally complex materials. However, in cases where a compound's refractive index is predominantly dictated by ionic interactions and density, the additional complexity of the ncalc approach may not yield results more accurate than nGD. As shown in Table 4, both the polarizability and the Gladstone–Dale approaches result in comparable accuracy in this case, with over 90 % of the entries showing less than 3 % deviation between calculated and observed mean refractive indices. Figure 6 further shows that the two methods produce similar trends in the calculated mean refractive indices compared to experimental values.

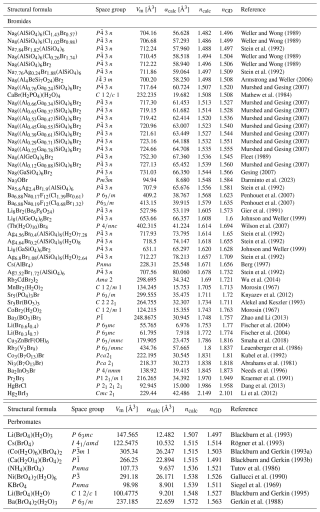

Using calculated electronic polarizabilities of I.53(5) Å3, No(I−) = 0.9 Å3.6, and Br.4(3) Å3, as well as No(Br−) = 1.00 Å3.6 and α([4]Br.938 Å3 resulting from this work, together with the extensive set of polarizability values listed by Shannon and Fischer (2016), including α([4]I.10 Å3 and α([6]I.00 Å3, a list of predicted mean refractive indices is presented in Tables 5 and 6. The crystal-structure data are taken from the ICSD database (Belsky et al., 2002), with the original literature cited in the last columns of Tables 5 and 6, under atmospheric pressure and allowing slight variations from room temperature.

The predicted refractive indices of iodides and periodates with four- and six-coordinated I7+ atoms, obtained from the polarizability approach, have been compared to those predicted using GD values. These results indicate that both calculated values are comparable in accuracy with respect to experimental data (see Fig. 7).

The refractive indices of bromides and perbromides containing [4]Br7+, predicted using polarizabilities, have been compared to those obtained using GD values (see Fig. 8).

As discussed by Shannon and Fischer (2016) and Shannon et al. (2017), systematic deviations from additivity in polarizability calculations occur in compounds with specific structural characteristics. These include structures featuring lone-pair electrons (such as I5+ and Br5+, which were excluded from this study because their lone-pair contributions cause deviations from typical polarizability behavior), uranyl ions, sterically strained (SS) frameworks, corner-shared octahedral (CSO) networks like perovskites and tungsten bronzes, edge-shared Fe3+ and Mn3+ octahedral (ESO) structures, and fast-ion conductors. These deviations indicate that additional structural and electronic factors influence polarizability beyond what is covered by standard additive models, highlighting the need for further refinement of predictive methods.

The empirically derived electronic polarizabilities of I−, Br−, and Br7+ were used to predict the mean refractive indices of selected iodide, bromide, and perbromate compounds. These predictions show reasonable agreement with other approaches, such as the Gladstone–Dale method, indicating that the derived values can provide useful estimates for the optical properties of halogen-containing compounds. The accuracy of the prediction can be estimated from the errors listed in Table 4 for the refractive indices calculated from the electronic polarizabilities. Omitting the two outliers of SiBr4 and GeBr4, the error for the refractive indices is less than 2 % for all entries and 0.9 % on average.

All relevant data required to calculate the empirical electronic polarizabilities of the target atoms are provided in Table 2. The empirical electronic polarizabilities of other elements are taken from Shannon and Fischer (2016). Tables 5 and 6 contain all information necessary for determining the predicted parameters.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/ejm-37-889-2025-supplement.

SN: optical and single-crystal X-ray diffraction measurements, data collection, determination of polarizabilities, writing the paper; PAF and FK: synthesis of NaBrO4 ⋅ H2O crystals; RXF: design and supervision of the project. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results and the preparation of the paper.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We thank Johannes Birkenstock (Bremen) for his support with the X-ray diffraction data collection, Iris Spieß (Bremen) for her assistance in the recrystallization of the samples, Olaf Medenbach (Bochum) for providing optical equipment, and Robert D. Shannon (Boulder) for his continuous support of this project.

This research was financially supported by a scholarship from Unit 12 (Research and Early-Career Researchers) of the University of Bremen to SN.

The article processing charges for this open-access publication were covered by the University of Bremen.

This paper was edited by Alessandro Pavese and reviewed by Marco Bruno and one anonymous referee.

Abrahams, S. C., Bernstein, J. L., and Svensson, C.: Orthorhombic phase of nickel bromine boracite Ni3B7O13Br: Room temperature ferroelectric-ferroelastic crystal structure, J. Chem. Phys., 75, 1912–1918, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.442216, 1981.

Ahtee, M.: Lattice constants of some binary alkali halide solid solutions, Ann. Acad. Sci. Fenn. A6: Physica., 313, 1–11, 1969.

Alekel III, T. and Keszler, D. A.: New strontium borate halides: Sr5(BO3)3X (X = F, Br), Inorg. Chem., 32, 101–105, https://doi.org/10.1021/ic00053a017, 1993.

Aleksandrova, M., Haeuseler, H., Jaquet, R., and Wagener, M.: Acidic salts of the decaoxodiperiodic acid: NiH4I2O10 ⋅ 6H2O, ZnH4I2O10 ⋅ 6H2O, and MgH4I2O10 ⋅ 6H2O; crystal structures, vibrational spectra, and thermal decomposition, Z. Naturforsch., B63, 1367–1376, https://doi.org/10.1515/znb-2008-1205, 2008.

Alexandrova, M. and Haeuseler, H.: Crystal structure, infrared and Raman spectra and thermal analysis of strontium-tetrahydrogen-hexaoxoperiodate-trihydrate, Sr(H4IO6)2 ⋅ 3H2O, J. Mol. Struct., 706, 7–13, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2003.12.069, 2004.

Anderson, O. L.: Optical properties of rock-forming minerals derived from atomic properties, Fortschr. Mineral., 52, 611–629, 1975.

Anderson, O. L. and Schreiber, E.: The relation between refractive index and density of minerals related to the Earth's mantle, J. Geophys. Res., 70, 1463–1471, https://doi.org/10.1029/JZ070i006p01463, 1965.

Appelman, E. H.: Perbromic acid and perbromates: synthesis and some properties, Inorg. Chem., 8, 223–227, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ic50072a008, 1969.

Armstrong, J. A. and Weller, M. T.: New sodalite frameworks; synthetic tugtupite and a beryllosilicate framework with a 3 : 1 Si : Be ratio, Dalton Transactions, 24, https://doi.org/10.1039/B600579A, 2006.

Ballard, S., Browder, J. S., and Ebersole, J. F.: Refractive index of special crystals and certain glasses, American Institute of Physics Handbook, 3rd Edn., Sect. 6b, edited by: Billings, B. H., McGraw-Hill, New York, 6-12–6-57, ISBN 007001485X, 9780070014855, 1972.

Barth, T. F. W.: Optical properties of mixed crystals, Am. J. Sci., s5–19, 135–146, https://doi.org/10.2475/ajs.s5-19.110.135, 1930.

Belsky, A., Hellenbrandt, M., Karen, V. L. and Luksch, P.: New developments in the inorganic crystal structure database (ICSD): accessibility in support of materials research and design, Acta Crystallogr., B58, 364–369, https://doi.org/10.1107/s0108768102006948, 2002.

Berg, R. W.: The CsBr-AlBr3 Phase diagram and the crystal structure of CsAlBr4, Acta Chemica Scandinavica, 51, 455–461, doinumber: 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.51-0455, 1997.

Berset, G., Depmeier, W., Boutellier, R., and Schmid, H.: Structure of boracite Cu3B7O13l, Acta Crystallogr., C41, 1694–1696, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108270185009106, 1985.

Bigoli, F., Manotti Lanfredi, A. M., Tiripicchio, A., and Tiripicchio Camellini, M.: Crystal and molecular structure of hexaquomagnesium trihydrogenhexaoxoiodate(VII), Acta Crystallogr., B26, 1075–1079, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0567740870003643, 1970.

Birkenstock, J., Fischer, R. X., and Messner, T.: BRASS, the Bremen Rietveld analysis and structure suite, Z. Kristallogr. Suppl., 23, 237–242, https://doi.org/10.1524/9783486992526-041, 2006.

Blackburn, A. C. and Gerkin, R. E.: Structure of hexaaquacobalt(II) perbromate, Acta Crystallogr., C49, 1271–1275, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108270192013465, 1993a.

Blackburn, A. C. and Gerkin, R. E.: Structure of tetraaquacalcium perbromate, Acta Crystallogr., C49, 1439–1442, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108270193001714, 1993b.

Blackburn, A. C. and Gerkin, R. E.: Lithium perbromate monohydrate at 296 and 173K, Acta Crystallogr., C51, 3–7, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108270194008449, 1995.

Blackburn, A. C., Gallucci, J. C., Gerkin, R. E., and Reppart, W. J.: Structure of sodium perbromate monohydrate, Acta Crystallogr., C48, 419–424, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108270191010818, 1992.

Blackburn, A. C., Gallucci, J. C., Gerkin, R. E., and Reppart, W. J.: Structure of lithium perbromate trihydrate, Acta Crystallogr., C49, 1437–1439, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108270193000538, 1993.

Bloss, F. D., Gunter, M., Su, S.-C., and Wolfe, H. E.: Gladstone-Dale constants; a new approach, Can. Mineral., 21, 93–99, 1983.

Borhade, A. V., Wakchaure, S. G., and Dholi, A. G.: One pot synthesis and crystal structure of aluminosilicate mixed chloro-iodo sodalite, Indian J. Phys., 84, 133–141, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12648-010-0032-0, 2010.

Botova, M., Botova, M., Nagel, R., Maneva, M., and Lutz, H. D.: Kristallstruktur, Infrarot- und Ramanspektren von Kupfertrihydrogenperiodatmonohydrat, CuH3IO6 ⋅ H2O, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem., 627, 333–340, https://doi.org/10.1002/1521-3749(200103)627:3<333::AID-ZAAC333>3.0.CO;2-I, 2001.

Botova, M., Nagel, R., and Haeuseler, H.: Präparation, Kristallstruktur, Schwingungsspektren und thermische Analyse von Kupfer-tetrahydrogen-decaoxo-diperiodat-hexahydrat CuH4I2O10 ⋅ 6H2O, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem., 630, 179–184, https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.200300252, 2004.

Braibanti, A., Tiripicchio, A., Bigoli, F., and Pellinghelli, M. A.: Crystal and molecular structure of cadmium trihydrogenhexaoxoiodate(VII) trihydrate, Acta Crystallogr., B26, 1069–1074 https://doi.org/10.1107/S0567740870003631, 1970.

Brehler, B., Jacobi, H., and Siebert, H.: Kristallstruktur und Schwingungsspektrum von K4J2O9, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem., 362, 301–311, https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.19683620510, 1968.

Currie, D. B., Levason, W., Oldroyd, R. D., and Weller, M. T.: Reinvestigation of the mixed-metal periodates M′MIO6 (M alkali metal, M = Ge, Sn, Pb), J. Mater. Chem., 3, 447–451, https://doi.org/10.1039/JM9930300447, 1993.

Dang, Y., Meng, X., Jiang, K., Zhong, C., Chen, X., and Qin, J.: A promising nonlinear optical material in the Mid-IR region: new results on synthesis, crystal structure and properties of noncentrosymmetric β-HgBrCl, Dalton T., 42, 9893–9897, https://doi.org/10.1039/C3DT50291K, 2013.

Darminto, B., Rees, G. J., Cattermull, J., Hashi, K., Diaz-Lopez, M., Kuwata, N., Turrell, S. J., Milan, E., Chart, Y., Di Mino, C., Lee, H. J., Goodwin, A. L., and Pasta, M.: On the origin of the non-Arrhenius Na-ion conductivity in Na3OBr, Angew. Chem. Int. Edit., 62, e202314444, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202314444, 2023.

Degen, T., Sadki, M., Bron, E., König, U., and Nénert, G.: The HighScore suite, Powder Diffraction, 29, S13–S18, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0885715614000840, 2014.

Dennis, L. M. and Hance, F. E.: Germanium. III. Germaniumtetrabromid und Germaniumtetrachlorid, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem., 122, 265–276, https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.19221220125, 1922.

Dufet, M. H.: Forme cristalline et propriétés optiques du bromure de baryum, Bulletin de la Société Française de Minéralogie, 26, 65–80, https://doi.org/10.3406/bulmi.1903.2673, 1903.

Edwards, A. J. and Hana, A. A. K.: Fluoride crystal structures. Part 34. Antimony pentafluoride–iodine trifluoride dioxide, J. Chem. Soc. Dalton., 1734–1736, https://doi.org/10.1039/DT9800001734, 1980.

Eggleton, R. A.: Gladstone-Dale constants for the major elements in silicates: Coordination number, polarizability and the Lorentz-Lorentz relation, Can. Mineral., 29, 525–532, 1991.

Elliott, P., Cooper, M. A., and Pring, A.: Barlowite, Cu4FBr(OH)6, a new mineral isostructural with claringbullite: Description and crystal structure, Mineral. Mag., 78, 1755–1762, https://doi.org/10.1180/minmag.2014.078.7.17, 2014.

Erdmann, H.: Die Salze des Rubidiums und ihre Bedeutung für die Pharmazie, Arch. Pharm., 232, 3–36, https://doi.org/10.1002/ardp.18942320103, 1894.

Fairchild, J. G.: Artificial jarosites- the separation of potassium from cesium, Am. Mineral., 18, 543–547, 1933.

Farrugia, L. J.: WinGX and ORTEP for Windows: An update, J. Appl. Crystallogr., 45, 849–854, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0021889812029111, 2012.

Feikema, Y. D.: The crystal structures of two oxy-acids of iodine. I. A study of orthoperiodic acid, H5IO6, by neutron diffraction, Acta Crystallogr., 20, 765–769, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0365110X66001828, 1966.

Feklichev, V. G.: Diagnostic Constants of Minerals, 1st Edn., Mir Publishers/CRC Press, Moscow, Russia/Boca Raton, Florida, ISBN 0849375401, 1992.

Ferrari, A., Braibanti, A., and Tiripicchio, A.: The crystal structure of tetrapotassium dihydrogendecaoxodiiodate(VII) octahydrate, Acta Crystallogr., 19, 629–636, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0365110X65004000, 1965.

Fischer, D., Müller, A., and Jansen, M.: Existiert eine Wurtzit-Modifikation von Lithiumbromid? Untersuchungen im System LiBr/LiI, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem., 630, 2697–2700, https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.200400352, 2004.

Fischer, R. X., Burianek, M., and Shannon, R. D.: POLARIO, a computer program for calculating refractive indices from chemical compositions, Am. Mineral., 103, 1345–1348, https://doi.org/10.2138/am-2018-6587, 2018.

Fleet, M. E.: Structures of sodium alumino-germanate sodalites [Na8(Al6Ge6O24)A2, A = Cl, Br, I], Acta Crystallogr., C45, 843–847, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108270188013964, 1989.

Gallucci, J. C., Gerkin, R. E., and Reppart, W. J.: Structure of nickel(II) perbromate hexahydrate at 296 K, Acta Crystallogr., C46, 1580–1584, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108270189013533, 1990.

Gerkin, R. E., Reppart, W. J., and Appelman, E. H.: The structure of barium perbromate trihydrate Ba(BrO4)2 ⋅ 3H2O, Acta Crystallogr., C44, 960–962, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108270188002215, 1988.

Gesing, T. M.: Structure and properties of tecto-gallosilicates II. sodium chloride, bromide and iodide sodalites, Z. Krist-Cryst. Mater., 222, 289–296, https://doi.org/10.1524/zkri.2007.222.6.289, 2007.

Gier, T. E., Harrison, W. T. A., and Stucky, G. D.: The synthesis and structure of some new sodalites: the lithium haloberyllophosphates and -arsenates, Angew. Chem. Int. Edit., 30, 1169–1171, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.199111691, 1991.

Gladstone, J. H. and Dale, T. P.: XIV. Researches on the refraction, dispersion, and sensitiveness of liquids, Philos. T. R. Soc., 153, 317–343, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstl.1863.0014, 1863.

Gundelach, E.: Die Dispersion von KBr-Kristallen im Ultraroten, Z. Phys., 66, 775–783, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01390801, 1930.

Gunter, M. E. and Ribbe, P. H.: Natrolite group zeolites: Correlations of optical properties and crystal chemistry, Zeolites., 13, 435–440, https://doi.org/10.1016/0144-2449(93)90117-L, 1993.

Gyulai, Z.: Die Dispersion einiger Alkalihalogenide im Ultravioletten, Z. Phys., 46, 80–87, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02055759, 1927.

Haase, M.: Kürzere Originalmitteilungen und Notizen. Die Dispersion des Ammoniumbromid, Z. Krist-Cryst. Mater., 80, 132–133, https://doi.org/10.1524/zkri.1931.80.1.132, 1931.

Haberkorn, R., Bauer, J., and Kickelbick, G.: Ba2PO4I, Sr2PO4I, and Pb2PO4I – A new structure type and three of its representatives, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem., 640, 3153–3158, https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.201400221, 2014.

Haeuseler, H. and Botova, M.: Zur Kenntnis von Calciumtetrahydrogen-hexaoxo-diperiodattetrahydrat CaH4I2O10 ⋅ 4H2O: Kristallstruktur, Schwingungsspektren und thermische Analyse, Z. Naturforsch., B57, 1337–1345, https://doi.org/10.1515/znb-2002-1201, 2002.

Haeuseler, H. and Wagener, M.: Crystal structure and vibrational spectra of BaH4I2O10 ⋅ 2H2O, J. Mol. Struct., 892, 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2008.04.039, 2008.

Han, X., Lahera, D. E., Serrano, M. D., Cascales, C., and Zaldo, C.: Ultraviolet to infrared refractive indices of tetragonal double tungstate and double molybdate laser crystals, Appl. Phys., B108, 509–514, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00340-012-4936-6, 2012.

Harting, H.: Die Brechzahlen einiger Halogenidkristalle, Sitzber. Deut. Akad. Wiss. Berlin, IV, 1, 1948.

Hellwege, K. H. and Hellwege, A. M.: Landolt-Börnstein, Band II. Teil 8. Optische Konstanten, Springer, Berlin, ISBN 3540051783, 1962.

Hoppe, R. and Schneider, J.: Eine “misslungene” Synthese: Über K4Li[IO6] und K5I2[AuO2], J. Less-Common Met., 137, 85–103, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5088(88)90078-1, 1988.

Hull, S., Keen, D. A., Sivia, D. S., and Berastegui, P.: Crystal structures and ionic conductivities of ternary derivatives of the silver and copper monohalides: I. Superionic phases of stoichiometry MA4I5: RbAg4I5, KAg4I5, and KCu4I5, J. Solid. State. Chem., 165, 363–371, https://doi.org/10.1006/jssc.2002.9552, 2002.

Hummel, T., Salk, F., Ströbele, M., Enseling, D., Jüstel, T., and Meyer, H.-J.: The orthoperiodates of calcium, strontium, and barium, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem., 977–981, https://doi.org/10.1002/ejic.201403094, 2015.

Jaffe, H. W.: Crystal Chemistry and Refractivity, Dover Books in Science and Mathematics, Dover Publications, ISBN 9780486691732, 1996.

Jansen, M. and Kraft, T.: Li2H3IO6, eine neue Variante der Molybdänitstruktur, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem., 620, 53–57, https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.19946200109, 1994.

Jemmer, P., Fowler, P. W., Wilson, M., and Madden, P. A.: Environmental effects on anion polarizability: Variation with lattice parameter and coordination number, J. Phys. Chem., A102, 8377–8385, https://doi.org/10.1021/jp982029j, 1998.

Johnson, G. M. and Weller, M. T.: Synthesis and characterisation of gallium and germanium containing sodalites, in: Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis, edited by: Chon, H., Ihm, S.-K., and Uh, Y. S., 105, 269–275, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2991(97)80565-4, 1997.

Johnson, G. M. and Weller, M. T.: A powder neutron diffraction study of lithium-substituted gallosilicate and aluminogermanate halide sodalites, Inorg. Chem., 38, 2442–2450, https://doi.org/10.1021/ic9812510, 1999.

Jones, E. M., Levason, W., Oldroyd, R. D., Webster, M., Thomas, M., and Hutchings, J.: Synthesis, spectroscopic and structural characterisation of periodate complexes of iron(III), J. Chem. Soc. Dalton., 3367–3373, https://doi.org/10.1039/DT9950003367, 1995.

Kellersohn, T.: Structure of potassium sodium orthoperiodate(VII) tetrahydrate Acta Crystallogr., C47, 1133–1136, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108270190013269, 1991.

Kent, G. T., Morgan, E., Albanese, K. R., Kallistova, A., Brumberg, A., Kautzsch, L., Wu, G., Vishnoi, P., Seshadri, R., and Cheetham, A. K.: Elusive Double Perovskite Iodides: Structural, Optical, and Magnetic Properties, Angew. Chem. Int. Edit., 62, e202306000, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202306000, 2023.

Knyazev, A. V., Chernorukov, N. G., and Bulanov, E. N.: Apatite-structured compounds: Synthesis and high-temperature investigation, Mater. Chem. Phys., 132, 773–781, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2011.12.011, 2012.

Kondo, H., Kobayashi, A., and Sasaki, Y.: The structure of the hexamolybdoperiodate anion in its potassium salt, Acta Crystallogr., B36, 661–664, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0567740880004037, 1980.

Korth, K.: Dispersionsmessungen an Kaliumbromid und Kaliumjodid im Ultraroten, Z. Phys., 84, 677–685, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01330491, 1933.

Kovalevskiy, A. and Jansen, M.: Synthesis, Crystal Structure Determination, and Physical Properties of Ag5IO6, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem., 632, 577–581, https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.200500476, 2006.

Kraemer, K., Meyer, G., Fischer, P., Hewat, A. W., and Güdel, H. U.: Neutron diffraction investigation of magnetic phase transitions to long-range antiferromagnetic ordering in the “free-electron” praseodymium halides Pr2X5 (X = Br, I), J. Solid. State. Chem., 95, 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4596(91)90370-W, 1991.

Kraft, T. and Jansen, M.: Zur Existenz des Tetrahydrogenorthoperiodations: Die Kristallstruktur von LiH4IO6 ⋅ H2O, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem., 620, 805–808, https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.19946200508, 1994.

Kraft, T. and Jansen, M.: Die Kristallstruktur von Lithiummetaperiodat, LiIO4, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem., 621, 484–487, https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.19956210326, 1995.

Kubel, F., Mao, S. Y., and Schmid, H.: Structure of the fully ferroelectric/fully ferroelastic orthorhombic room-temperature phase of cobalt bromine boracite, Co3B7O13Br and nickel chlorine boracite, Ni3B7O13Cl, Acta Crystallogr., C48, 1167–1170, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108270191014129, 1992.

Kublitzky, A.: Einige optische Konstanten von Alkalihalogenidkristallen, Ann. Phys-Berlin., 412, 793–808, https://doi.org/10.1002/andp.19344120708, 1934.

Larsen, E. S.: The microscopic determination of the nonopaque minerals (Bulletin 679), United States Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, https://doi.org/10.3133/b679, 1921.

Leuenberger, B., Briat, B., Canit, J. C., Furrer, A., Fischer, P., and Guedel, H. U.: Synthesis, structural characterization, and magnetic properties of V3+ dimer compounds. Neutron scattering and magnetic circular dichroism study of Cs3V2Cl9 and Rb3V2Br9, Inorg. Chem., 25, 2930–2935, https://doi.org/10.1021/ic00237a003, 1986.

Li, Y., Wang, M., Zhu, T., Meng, X., Zhong, C., Chen, X., and Qin, J.: Synthesis, crystal structure and properties of a new candidate for nonlinear optical material in the IR region: Hg2BrI3, Dalton. T., 41, 763–766, https://doi.org/10.1039/C1DT11317H, 2012.

Lorentz, H. A.: Ueber die Beziehung zwischen der Fortpflanzungsgeschwindigkeit des Lichtes und der Körperdichte, Ann. Phys.-Berlin, 245, 641–665, https://doi.org/10.1002/andp.18802450406, 1880.

Lorenz, L.: Ueber die Refractionsconstante, Ann. Phys.-Berlin, 247, 70–103, https://doi.org/10.1002/andp.18802470905, 1880.

Mandarino, J. A.: The Gladstone-Dale relationship, Part I, Derivation of new constants, Can. Mineral., 14, 498–502, 1976.

Mandarino, J. A.: The Gladstone-Dale relationship, Part III, Some general applications, Can. Mineral., 17, 71–76, 1979.

Mandarino, J. A.: The Gladstone-Dale relationship, Part IV, The compatibility concept and its application, Can. Mineral., 19, 441–450, 1981.

Mathew, M., Takagi, S., and Brown, W. E.: Planar Ca-PO4 sheet-Type structures: calcium bromide dihydrogenphosphate tetrahydrate, CaBr(H2PO4) ⋅ 4H2O, and calcium iodide dihydrogenphosphate tetrahydrate, CaI(H2PO4) ⋅ 4H2O, Acta Crystallogr., C40, 1662–1665, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108270184009082, 1984.

Mattes, R. and Richter, K.-L.: Darstellung und Struktur des Polyvanadato-periodates Na6[H2V2I2O16] ⋅ 10H2O, Z. Naturforsch., B37, 1241–1244, https://doi.org/10.1515/znb-1982-1005, 1982.

Mattes, R., Matz, C., and Sicking, E.: Monomolybdato- und Monowolframato-perjodate: Die Kristallstruktur von K6[Mo2J2O16] ⋅ 10 H2O, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem., 435, 207–213, https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.19774350128, 1977.

May, A., Sjoberg, J. J., and Baglin, E. G.: Synthetic argentojarosite: physical properties and thermal behavior, Am. Mineral., 58, 936–941, 1973.

Merwin, H. E.: International Critical Tables, McGraw-Hill Book Co., New York, NY, Vol. 7, p. 27, ISBN 978-1015896604, 1930.

Mormann, Th. J. and Jeitschko, W.: Crystal structure of trimercury(II) dihydrogenhexaoxoiodate(VII), Hg3(H2IO6)2, Z. Krist. New. Cryst. St., 215, 315–316, https://doi.org/10.1515/ncrs-2000-0303, 2000.

Mormann, Th. J. and Jeitschko, W.: Crystal structure of mercury(II) trihydrogenhexaoxoiodate(VII), HgH3IO6, Z. Krist. New. Cryst. St., 216, 1–2, https://doi.org/10.1524/ncrs.2001.216.14.1, 2001.

Morosin, B.: Crystal Structure of manganese (II) and cobalt (II) bromide dihydrate, J. Chem. Phys., 47, 417–420, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1711911, 1967.

Mudring, A.-V. and Babai, A.: [Nd6(μ6-O)(μ3-OH)8(H2O)24]I8(H2O)12 the first basic rare earth iodide with an oxygen-centred M6X8-cluster core, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem., 631, 261–263, https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.200400377, 2005.

Murshed, M. M. and Gesing, T. M.: Isomorphous gallium substitution in the alumosilicate sodalite framework: synthesis and structural studies of chloride and bromide containing phases, Z. Krist-Cryst. Mater., 222, 341–349, https://doi.org/10.1524/zkri.2007.222.7.341, 2007.

Nesse, W. D.: Introduction to Optical Mineralogy, 2nd Edn., Oxford University Press, New York, ISBN 0195060245, 2013.

Needs, R. L., Weller, M. T., Scheler, U., and Harris, R. K.: Synthesis and structure of Ba2InO3X (X = F, Cl, Br) and Ba2ScO3F; oxide/halide ordering in K2NiF4-type structures, J. Mater. Chem., 6, 1219–1224, https://doi.org/10.1039/JM9960601219, 1996.

Nezamabadi, S.: Determination of the electronic polarizabilities of bromine in bromides, bromates, and perbromates, Master thesis, University of Bremen, 2023.

O'Sullivan, S. E., Montoya, E., Sun, S.-K., George, J., Kirk, C., Dixon Wilkins, M. C., Weck, P. F., Kim, E., Knight, K. S., and Hyatt, N. C.: Crystal and Electronic Structures of A2NaIO6 Periodate Double Perovskites (A = Sr, Ca, Ba): Candidate Wasteforms for I-129 Immobilization, Inorg. Chem., 59, 18407–18419, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c03044, 2020.

Palik, E. D. (Ed.): Handbook of Optical Constants of Solids II, Academic Press, College Park, Maryland, ISBN 0-12-544422-2, 1991.

Palik, E. D. (Ed.): Handbook of Optical Constants of Solids III, Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-544423-0, 1998.

Penhouet, T., Hagemann, H., Kubel, F., and Rief, A.: Calcium-free solid solutions in the system Ba7F12Cl2−xBrx (x < 1.5), a single-component white phosphor host, J. Chem. Crystallogr., 37, 469–472, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10870-007-9195-8, 2007.

Pfitzner, A., Lutz, H. D., and Cockcroft, J. K.: Li2ZnI4: A neutron powder study, J. Solid State Chem., 87, 463–466, https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4596(90)90050-8, 1990.

Pogue, E. A., Bond, J., Imperato, C., Abraham, J. B. S., Drichko, N., and McQueen, T. M.: A gold(I) oxide double perovskite: Ba2AuIO6, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 143, 19033–19042, https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.1c08241, 2021.

Rögner, P., Schießl, U., and Range, K.-J.: On the space group of cesium perbromate, CsBrO4, Z. Naturforsch., B48, 235–236, https://doi.org/10.1515/znb-1993-0219, 1993.

Rosu, C. and Weakley, T. J. R.: Disodium chromium(III) hexamolybdoiodate(VII) 24-hydrate, Na2Cr[IMo6O24] ⋅ 24H2O, Acta Crystallogr., C56, e170–e171, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108270100005229, 2000.

Sarp, H., Pushcharovsky, D. Y., MacLean, E. J., Teat, S. J., and Zubkova, N. V.: Tillmannsite, (Ag3Hg)(V,As)O4, a new mineral: its description and crystal structure, Eur. J. Mineral., 15, 177–180, https://doi.org/10.1127/0935-1221/2003/0015-0177, 2003.

Sasaki, M., Yarita, T., and Sato, S.: Ba(H3IO6), Acta Crystallogr., C51, 1968–1970, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108270195004744, 1995.

Shannon, R. D.: Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides, Acta Crystallogr., A32, 751–761, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0567739476001551, 1976.

Shannon, R. D.: Dielectric polarizabilities of ions in oxides and fluorides, J. Appl. Phys., 73, 348–366, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.353856, 1993.

Shannon, R. D. and Fischer, R. X.: Empirical electronic polarizabilities in oxides, hydroxides, oxyfluorides, and oxychlorides, Phys. Rev., B73, 235111, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.73.235111, 2006.

Shannon, R. D. and Fischer, R. X.: Empirical electronic polarizabilities of ions for the prediction and interpretation of refractive indices: Oxides and oxysalts, Am. Mineral., 101, 2288–2300, https://doi.org/10.2138/am-2016-5730, 2016.

Shannon, R. C., Lafuente, B., Shannon, R. D., Downs, R. T., and Fischer, R. X.: Refractive indices of minerals and synthetic compounds, Am. Mineral., 102, 1906–1914, https://doi.org/10.2138/am-2017-6144, 2017.

Sheldrick, G. M.: Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL, Acta Crystallogr., C71, 3–8, https://doi.org/10.1107/S2053229614024218, 2015.

Siegel, S., Tani, B., and Appelman, E.: Crystal structure of potassium perbromate, Inorg. Chem., 8, 1190–1191 https://doi.org/10.1021/ic50075a036, 1969.

Smaha, R. W., He, W., Sheckelton, J. P., Wen, J., and Lee, Y. S.: Synthesis-dependent properties of barlowite and Zn-substituted barlowite, J. Solid. State. Chem., 268, 123–129, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2018.08.016, 2018.

Spangenberg, K.: Dichte und Lichtbrechung der Alkalihalogenide, Z. Krist-Cryst. Mater., 57, 494–534, https://doi.org/10.1524/zkri.1922.57.1.494, 1922.

Sprockhoff, M.: Beiträge zu den Beziehungen zwischen dem Krystall und seinem chemischen Bestand, Neues. Jahrb. Geol. Paläontol, Beilagen-Band., 18, 151, 117–154, 1903.

Stein, A., Ozin, G. A., Macdonald, P. M., Stucky, G. D., and Jelinek, R.: Silver, sodium halosodalites: class A sodalites, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 114, 5171–5186, https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00039a032, 1992.

Subban, B. and Dhanraj, R.: Luminescence and structural characterization on praseodymium (Pr3+) doped potassium bromide (KBr) single crystals, Luminescence., 33, 885–890, https://doi.org/10.1002/bio.3486, 2018.

Swanson, H. and Fuyat, E.: Standard X-ray Diffraction Powder Patterns, National Bureau of Standards Circular 539, Vol. 2, Washington, D.C., U.S. Government Printing Office, https://doi.org/10.6028/NBS.CIRC.539v2, 1953.

Swanson, H. and Tatge, R. K.: Standard X-ray Diffraction Powder Patterns, National Bureau of Standards Circular 539, Vol. 1, Washington, D.C., U.S. Government Printing Office, https://doi.org/10.6028/NBS.CIRC.539v1, 1953.

Swanson, H. E., Fuyat, R. K., and Ugrinic, G. M.: Standard X-ray Diffraction Powder Patterns, National Bureau of Standards Circular 539, Vol. 3, Washington, D.C., U.S. Government Printing Office, https://doi.org/10.6028/NBS.CIRC.539v3, 1954.

Swanson, H., Fuyat, R. K., and Ugrinic, G. M.: Standard X-ray Diffraction Powder Patterns, National Bureau of Standards Circular 539, Vol. 4, Washington, D.C., U.S. Government Printing Office, https://doi.org/10.6028/NBS.CIRC.539v4, 1955a.

Swanson, H., Gilfrich, N. T., and Ugrinic, G. M.: Standard X-ray Diffraction Powder Patterns, National Bureau of Standards Circular 539, Vol. 5, Washington, D.C., U.S. Government Printing Office, https://doi.org/10.6028/NBS.CIRC.539v5, 1955b.

Swanson, H. E., Gilfrich, N. T., and Cook, M. I.: Standard X-ray Diffraction Powder Patterns, National Bureau of Standards Circular 539, Vol. 7, Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, https://doi.org/10.6028/NBS.CIRC.539v7, 1957.

Timofte, T., Babai, A., Meyer, G., and Mudring, A.-V.: Praseodymium triiodide nonahydrate, Acta Crystallogr., E61, i94–i95, https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600536805012857, 2005.

Topsoe, H. and Christiansen, C.: Recherches optiques sur quelques séries de substances isomorphes, 5th ser., 21, Crochard / V. Masson, Paris, ISBN 1273201892, 1874.

Tutov, A. G., Gavrilov, V. V., Isupov, V. K., Kolycheva, T. I., and Fundamenskii, V. S.: Preparation and X-ray structure analysis of crystals of rubidium and ammonium perbromates, Zh. Neorg. Khim., 31, 589–592, 1986.

Untenecker, H. and Hoppe, R.: Ein neues Periodat. Zum Aufbau von K9Li3I2O13= K9Li3O[IO6]2, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem., 549, 129–138, https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.19875490613, 1987.

Verbist, J., Piret, P., and Van Meerssche, M.: Structure cristalline et protonique de l'iodure de sodium dihydraté NaI ⋅ 2H2O, B. Soc. Fr. Mineral. Cr., 93, 509–514, https://doi.org/10.3406/bulmi.1970.6506, 1970.

Volkov, S. N., Charkin, D. O., Arsent'ev, M. Y., Povolotskiy, A. V., Stefanovich, S. Y., Ugolkov, V. L., Krzhizhanovskaya, M. G., Shilovskikh, V. V., and Bubnova, R. S.: Bridging the salt-inclusion and open-framework structures: The case of acentric Ag4B4O7X2 (X = Br, I) borate halides, Inorg. Chem., 59, 2655–2658, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c00306, 2020.

Waal, D. D., Zabel, M., and Range, K.-J.: The crystal structure of β-CsIO4, the room-temperature modification of cesium periodate, Z. Naturforsch., B51, 441–443, https://doi.org/10.1515/znb-1996-0323, 1996.

Weast, R. C., Astle, M. J., and Beyer, W. H.: CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 66th Edn., CRC Press, United States, ISBN 0849304857, 1985.

Weller, M. T. and Wong, G.: Mixed halide sodalites, Eu. J. Solid state Inorg. Chem., 26, 619–633, 1989.

Wernicke, W.: Ueber die Brechung und Dispersion des Lichtes in Jod-, Brom- und Chlorsilber, Ann. Phys., 142, 560–573, https://gallic a.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k15226m, 1871.

Wilson, R. E., Skanthakumar, S., Burns, P. C., and Soderholm, L.: Structure of the homoleptic thorium(IV) Aqua Ion [Th(H2O)10]Br4, Angew. Chem. Int. Edit., 46, 8043–8045, https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.200702872, 2007.

Winchell, A. N.: Elements of Optical Mineralogy, An Introduction to Microscopic Petrography, John Wiley and Sons, New York, ISBN 140670055X, 1933.

Winchell, N. H. and Winchell, A. N.: The Microscopic Characters of Artificial Inorganic Solid Substances or Artificial Minerals, John Wiley and Sons, New York, 1931.

Wu, Q., Meng, X., Zhong, C., Chen, X., and Qin, J.: Rb2CdBr2I2: A new IR nonlinear optical material with a large laser damage threshold, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 136, 5683–5686, https://doi.org/10.1021/ja412405u, 2014.

Wu, Q., Liu, X., Xu, S., Pi, H., Han, X., Liu, Y., and Li, Y.: Synthesis, crystal structures and nonlinear optical properties of β-RbCdI3 ⋅ H2O and CsCdI3 ⋅ H2O, Dalton. T., 48, 6787–6793, https://doi.org/10.1039/C9DT01408J, 2019.

Wulff, P. and Schaller, D.: Refraktometrische Messungen an Kristallen und Vergleich isomorpher Salze mit edelgasähnlichen und edelgasunähnlichen Kationen: 8. Mitteilung über Refraktion und Dispersion von Kristallen, Z. Krist-Cryst. Mater., 87, 43–71, https://doi.org/10.1524/zkri.1934.87.1.43, 1934.

Zhang, Z., Suchanek, E., Eßer, D., Lutz, H. D., Nikolova, D., and Maneva-Petrova, M.: NiH3IO6 ⋅ 6H2O Kristallstruktur und Schwingungsspektren, Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem., 622, 845–852, https://doi.org/10.1002/zaac.19966220516, 1996.

Zhao, J. and Li, R. K.: Two new barium borate bromides: Ba2BO3Br and Ba3BO3Br3, Solid. State. Sci., 24, 54–57, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2013.07.009, 2013.

The requested paper has a corresponding corrigendum published. Please read the corrigendum first before downloading the article.

- Article

(1239 KB) - Full-text XML

- Corrigendum

-

Supplement

(278 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote