the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Zhenruite, (MoO3)2 ⋅ H2O, and tianhuixinite, (MoO3)3 ⋅ H2O, two new minerals in the MoO3–MoO3 ⋅ 2H2O system

Xiangping Gu

Hexiong Yang

Ronald B. Gibbs

Guanghua Liu

Two new minerals, zhenruite, ideally (MoO3)2⋅H2O, and tianhuixinite, ideally (MoO3)3⋅H2O, were discovered, respectively, from the Freedom #2 mine in the central part of the Marysvale volcanic field, Utah, USA, and an unnamed short adit on the Summit group of claims near Cookes Peak, Luna County, New Mexico, USA. Zhenruite occurs as acicular or prismatic crystals (up to mm). Associated minerals include alunogen, anhydrite, coquimbite, fluorite, liangjunite, quartz, and raydemarkite. Zhenruite is colorless in transmitted light and transparent with a white streak and vitreous luster. It is brittle with a Mohs hardness of 1 –2; cleavage is perfect on {001}. The calculated density is 4.081 g cm−3. Tianhuixinite occurs as nanometric crystal aggregates, 10–70 µm in size, intergrown with virgilluethite. Associated minerals include barite, fluorite, ilsemannite, jordisite, powellite, pyrite, quartz, raydemarkite, sidwillite, and virgilluethite. Tianhuixinite is dark blue-green and translucent in transmitted light. It has a white streak and vitreous luster. Tianhuixinite is brittle with a Mohs hardness of ∼2; no cleavage was observed. The calculated density is 4.131 g cm−3. At room temperature, neither zhenruite nor tianhuixinite is soluble in water or hydrochloric acid. Electron microprobe analyses yielded an empirical formula (Mo1.00O3)2⋅H2O for zhenruite and (Mo1.00O3)3⋅H2O for tianhuixinite, calculated on the basis of 7 and 10 O apfu, respectively.

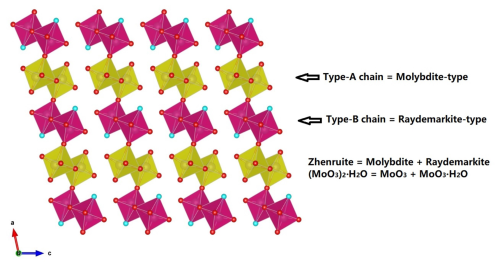

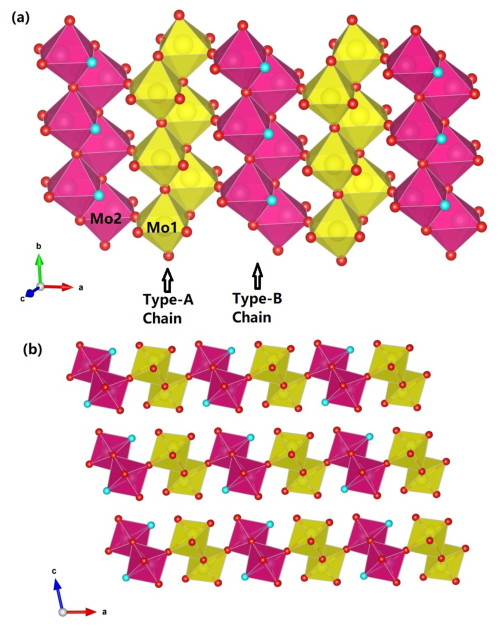

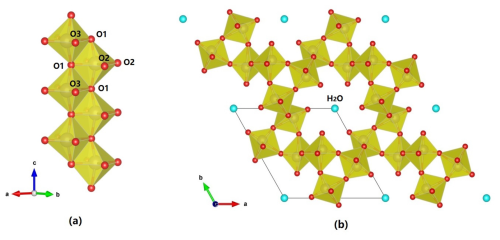

Zhenruite and tianhuixinite are the natural counterparts of synthetic (MoO3)2⋅H2O and hexagonal (MoO3)3⋅H2O, respectively. Zhenruite is monoclinic with space group P2 and unit-cell parameters a=9.6790(6), b=3.70653(19), c=7.1029(4) Å, β=102.391(5)°, V=248.89(2) Å3, and Z=2. Its crystal structure is characterized by two kinds of topologically identical octahedral double chains extending along [010], one consisting of edge-sharing Mo1O6 octahedra only and the other Mo2O5(H2O) octahedra only. These two kinds of chains are linked together alternately through sharing corners to form layers parallel to (001), which are interconnected by hydrogen bands along [001]. Tianhuixinite is hexagonal with space group P6 and unit-cell parameters a=10.5963(12), c=3.7216(4) Å, V=361.88(9) Å3, and Z=2. Its crystal structure is composed of double chains of edge-sharing MoO6 octahedra extending along [001], which are corner-connected with one another to form hexagonal channels with H2O residing at the center. The double chains of edge-sharing MoO6 octahedra in zhenruite and tianhuixinite are topologically identical to those in molybdite and raydemarkite, and zhenruite can be regarded as a combination of molybdite and raydemarkite both structurally and chemically. The discovery of tianhuixinite implies the likelihood of finding the ammonia analogue, (MoO3)3⋅NH3, in nature.

- Article

(12285 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(510 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Materials in the MoO3–MoO3⋅2H2O system, namely molybdenum trioxide (MoO3) and its related hydrates (MoO3⋅nH2O, , , 1, and 2), have been a subject of numerous studies for over a century owing to their versatile applications in electronics, catalysis, sensors, energy-storage units, field-emission devices, lubricants, super-conductors, thermal materials, biosystems, chromogenics, and electrochromic systems (see a thorough review by de Castro et al., 2017, and references therein). For MoO3, five polymorphs have been reported. In addition to the orthorhombic α form (Bräkken, 1931; Wooster, 1931; Andersson and Magnéli, 1950; Kihlborg, 1963; Sitepu, 2009), which is thermodynamically stable under ambient conditions and has been found in nature (named molybdite) (Čech and Povondra, 1963), four other metastable polymorphs include the monoclinic β-MoO3 and β′-MoO3 modifications (McCarron, 1986; Parise et al., 1991; Mougin et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2009), the high-pressure monoclinic (P2) MoO3-II phase (McCarron and Calabrese, 1991), and the hexagonal (P6) h-MoO3 phase (e.g., Wang et al., 2021; Li et al., 2024, and references therein). For MoO3⋅nH2O, six different phases have been reported, including (1) monoclinic P2 dihydrate MoO3⋅2H2O (Krebs, 1972; Césbron and Ginderow, 1985), (2) monoclinic yellow dihydrate MoO3⋅2H2O (Schultén, 1903; Lindqvist, 1950), (3) triclinic P-1 white monohydrate α-MoO3⋅H2O (Rosenheim and Davidsohn, 1903; Böschen and Krebs, 1974; Oswald et al., 1975), (4) monoclinic P2 yellow monohydrate β-MoO3⋅H2O (Rosenheim and Davidsohn, 1903; Günter, 1972; Boudjada et al., 1993), (5) monoclinic P2 hemihydrate MoOH2O (Fellows et al., 1983; Bénard et al., 1994), and (6) hexagonal P6 MoO3⋅1/3H2O (e.g., Fu et al., 2005; Deki et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2009; Lunk et al., 2010). Among these six hydrated MoO3⋅nH2O phases, five have been discovered in nature, including sidwillite, monoclinic P2 MoO3⋅ 2H2O (Césbron and Ginderow, 1985); raydemarkite, triclinic P-1 α-MoO3⋅H2O (Yang et al., 2023b); virgilluethite, monoclinic β-MoO3⋅H2O (Yang et al., 2023a); zhenruite, monoclinic P2 (MoO3)2⋅H2O (or MoOH2O); and tianhuixinite, hexagonal P6 (MoO3)3⋅H2O (or MoO3⋅1/3H2O). This paper describes the physical and chemical properties of zhenruite and tianhuixinite and their crystal structures determined from single-crystal X-ray diffraction data.

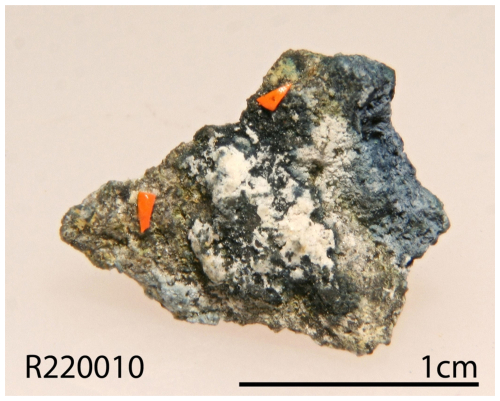

The new mineral zhenruite honors the late Chinese mineralogist, Prof. Zhenru Zhang (1930–2002), at the Central South University, Changsha, Hunan Province. Prof. Zhang graduated from the Department of Geology of Nanjing University in 1952 and started his teaching and research career at the Department of Geology, Central South University. As one of the pioneering teachers of the university, Prof. Zhang taught, among others, crystallography and mineralogy, ore geology, and modern analytical techniques for rocks and minerals. He was an eminent mineralogist and had made important contributions to clay mineralogy in ceramics and ore mineralogy in nonferrous metals and gold deposits with over 44 articles and 3 books. The new mineral tianhuixinite is named in honor of the late Chinese mineralogist, Prof. Huixin Tian (1933–2015), at Chengdu University of Technology, Sichuan Province, China. Prof. Tian graduated from the Changchun Institute of Geology in 1956 (now known as the School of Geosciences, Jilin University). Since 1960, she had been engaged in teaching and research at the Chengdu University of Technology until her retirement. As one of the pioneering teachers of mineralogy at the university, Prof. Tian taught, among others, crystallography and mineralogy, rare metal element mineralogy, and genetic mineralogy. During her more than 40-year academic career, she had made significant contributions to ore mineralogy, ore genesis, and exploration mineralogy, especially to Ti- and V-bearing magnetite deposits, tin deposits in Sichuan Province, and gold-tin deposits in Xinjiang Province. Both new minerals and their names have been approved by the Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification (CNMNC) of IMA (IMA 2022-050 and IMA 2022-081 for zhenruite and tianhuixinite, respectively). Parts of the cotype samples have been deposited at the University of Arizona Alfie Norville Gem and Mineral Museum (catalogue nos. 22720 and 22072 for zhenruite and tianhuixinite, respectively) and the RRUFF Project (deposition nos. R220010 and 220024) (http://rruff.net, last access: 10 January 2026).

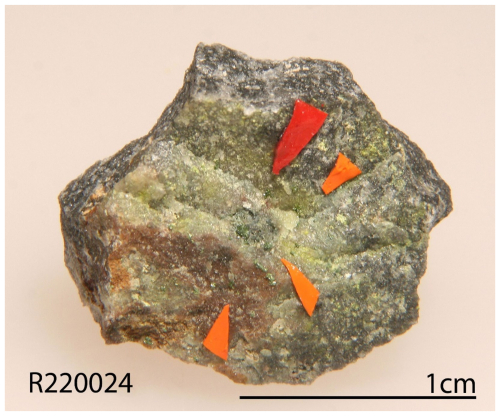

2.1 Occurrence

Zhenruite was found on specimens (Fig. 1) collected from the Freedom #2 mine in the Central Mining Area (38°29′43′′ N, 112°12′55′′ W), about 5.6 km north-northeast of the town of Marysvale in the central part of the Marysvale volcanic field, Utah, USA. This mine is also the type locality for umohoite (UO2)(MoO4)⋅2H2O, liangjunite K2(Mo2O5)(SO4)2⋅3H2O, wangpuite K3(PO4)(Mo12O36), downsite K2(MoO3)3(SO4)⋅4H2O, vanpeltite (Mo2O5)(S4+O3)⋅4H2O, and fanguangite (MoO2)(PO3OH)⋅4H2O. Associated minerals include alunogen, anhydrite, coquimbite, fluorite, liangjunite, quartz, and raydemarkite.

Figure 2A specimen on which the new minerals tianhuixinite and virgilluethite were discovered on a quartz matrix.

The Marysvale U-Mo deposit was formed in an epithermal vein system hosted in a volcanic/hypabyssal complex composed of porphyritic quartz monzonite, fine-grained granite, and glassy alkali rhyolite dated between 23 and 18 Ma (Brophy and Kerr, 1953; Cunningham et al., 1998). The samples containing zhenruite are the weathered product of the primary molybdenum ores exposed on the surface of the mine.

Tianhuixinite was found on a specimen (Fig. 2) collected by Ray Demark on 18 February 2016 in an unnamed short adit of the Summit group of claims (32°33′47′′ N and 107°43′48′′ W) near Cookes Peak, at the southern end of the Cookes Range, Luna County, New Mexico, USA. This place is also the type locality for raydemarkite, virgilluethite, and stunorthropite (NH4)2(Mo2O7). Associated minerals are barite, fluorite, ilsemannite, jordisite, powellite, pyrite, quartz, raydemarkite, sidwillite, and virgilluethite.

The Summit group of claims consists of a number of adits, shafts, pits, and trenches, many of which are rich in fluorite. Hydrothermal solutions originating from a granodiorite produced ore bodies localized in limestone units beneath impermeable shales, a process subsequently accompanied by silicification, the latter leading to the formation of jasperoids. The Summit group was one of the largest lead, zinc, and silver producers in the district (McLemore et al., 2001). The upper levels of the mines were highly oxidized and have been completely mined out. A more detailed summary of the geology and mineralogy of Cookes Peak mining district is presented by Simmons (2019).

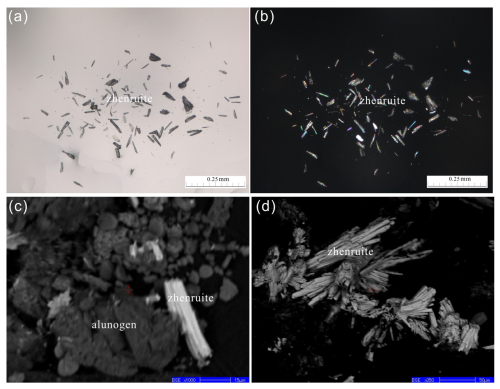

Figure 3A microscopic view of zhenruite captured by (a) a photomicrograph of the transmittance light microscope in parallel nicols. (b) The same view as (a), showing acicular and prismatic crystals of zhenruite and its interference color in crossed nicols. (c, d) Back-scattered electron image showing an agglomerate of acicular crystals of zhenruite with alunogen.

2.2 Appearance, physical properties, and chemical properties

Zhenruite occurs as acicular or prismatic crystals elongated along [010] (Fig. 3). Individual crystals of zhenruite are up to µm. It is colorless in transmitted light and transparent with a white streak and vitreous luster. It is brittle with a Mohs hardness of 1 –2; cleavage is perfect on {001}. No twinning was observed visually. The density was not measured due to the small crystal size and limited sample. The calculated density is 4.081 g cm−3 on the basis of the empirical formula and unit-cell volume from single-crystal X-ray diffraction data.

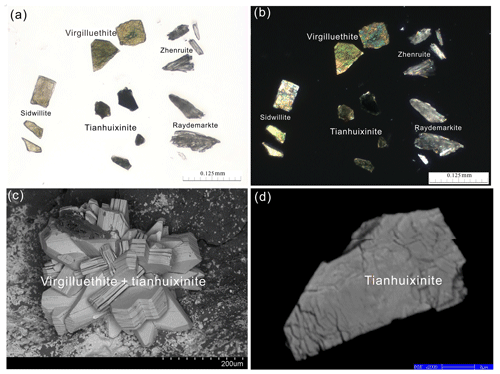

Figure 4A microscopic view of yellow-green intergrowths of platy tianhuixinite and virgilluethite crystals on a quartz matrix.

Figure 5Photomicrograph and electron images of tianhuixinite. (a) Photomicrograph in a transmittance light microscope in parallel nicols, showing grains of tianhuixinite with a darker blue-green color and lower transparency as compared to raydemarkite, virgilluethite and sidwillite. (b) The same view as (a) in a transmittance light microscope in crossed nicols. (c) Secondary electron image of the crystals of virgilluethite intergrown with tianhuixinite. (d) Back-scattered electron image showing the internal texture of tianhuixinite with microcleavages.

Tianhuixinite occurs as nanometric crystal aggregates, translucent in transmitted light and 10–70 µm in size, intergrown with virgilluethite (Figs. 4, 5). It has a darker blue-green color and lower transparency than virgilluethite, raydemarkite, or sidwillite. Tianhuixinite has a white streak and vitreous luster. It is brittle with a Mohs hardness of ∼2; cleavage was not observed. The density was not measured due to the small crystal size and limited sample. The calculated density is 4.131 g cm−3, based on the empirical formula and unit-cell volume from powder X-ray diffraction data. No optical data were determined for tianhuixinite or zhenruite because the indices of refraction are too high for measurement with available index liquids. The calculated average index of refraction is 1.996 for tianhuixinite and 1.990 for zhenruite for the empirical formula based on the Gladstone–Dale relationship (Mandarino, 1981).

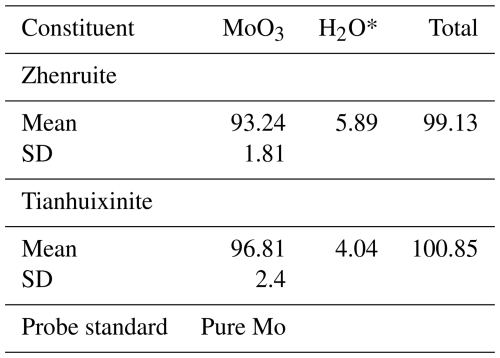

The chemical compositions of both zhenruite and tianhuixinite were determined with a Shimadzu-1720 electron microprobe operated at 15 keV and 10 nA with a beam size of 2 µm. The analytical data (average of seven analyses for zhenruite and eight for tianhuixinite) are given in Table 1, along with the standards used for the probe analyses. The resultant empirical chemical formulas are (Mo1.00O3)2⋅H2O for zhenruite and (Mo1.00O3)3⋅H2O for tianhuixinite, which were calculated on the basis of 7 and 10 O apfu, respectively. The ideal formula of zhenruite, (MoO3)2⋅H2O, requires (wt %) MoO3 94.11 and H2O 5.89 (total = 100 %), and that of tianhuixinite, (MoO3)3⋅H2O, requires MoO3 96.00 and H2O 4.00 (total = 100 %). At room temperature, neither zhenruite nor tianhuixinite is soluble in H2O.

2.3 Raman spectra

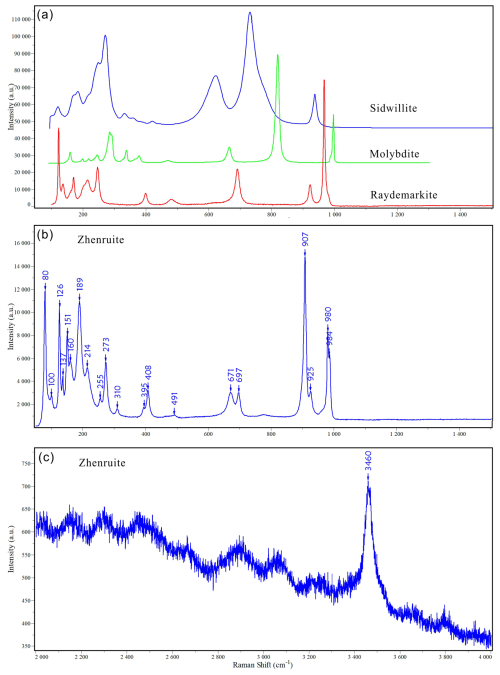

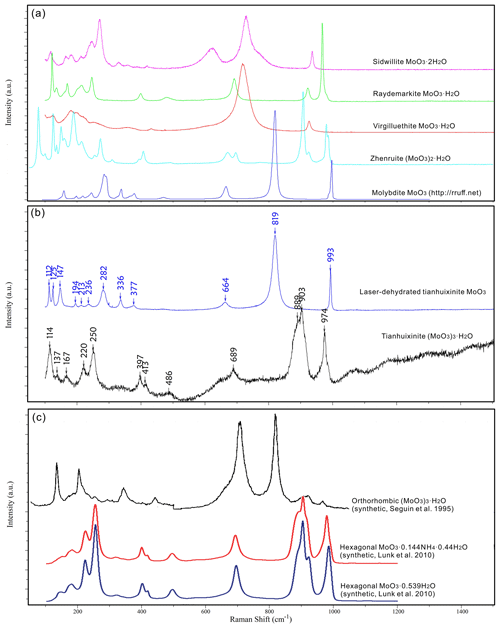

The Raman spectra of both zhenruite and tianhuixinite (Figs. 6, 7) were collected from a randomly oriented crystal on a Horiba ARAMIS micro-Raman system, using a solid-state laser with a wavelength of 532 nm and a thermoelectrically cooled CCD detector, with 2 cm−1 resolution and a spot size of 1 µm.

The Raman spectrum of zhenruite is shown in Fig. 6. The band at 3460 cm−1 is assigned to the O–H stretching vibrations in H2O. The bands at 907, 925, 980, and 984 cm−1 are attributed to the Mo–O stretching vibrations. The bands between 280 to 700 cm−1 are ascribable to the Mo–O–Mo and O–Mo–O bending vibrations. The bands below 280 cm−1 are mainly associated with the rotational and translational modes of MoO6 octahedra and H2O groups, as well as the lattice vibrational modes.

The Raman spectrum of tianhuixinite is identical to that of synthetic hexagonal P6 MoO3⋅xNH4⋅yH2O () (e.g. Lunk et al., 2010) but noticeably different from the spectra for sidwillite, raydemarkite, virgilluethite, and synthetic orthorhombic MoO3⋅0.33H2O (e.g. Seguin et al., 1995) (Fig. 7). The characteristic peaks of H2O between 2000–4000 cm−1 are not detected. It is noted that tianhuixinite is dehydrated to molybdite when the laser power is increased from 2.5 mW (D1 filter) to 6 mW (0.6 filter), as shown by the Raman spectrum of the latter (Fig. 7). According to the vibration mode analysis on MoO3⋅xH2O () by Seguin et al. (1995), the bands at 889, 903, and 689 cm−1 are attributed to the Mo–O stretching vibrations. The bands between 200 and 500 cm−1 are ascribable to the Mo–O–Mo and O–Mo–O bending vibrations. The bands below 200 cm−1 are mainly associated with the rotational and translational modes of MoO6 octahedra and H2O groups, as well as the lattice vibrational modes.

2.4 X-ray crystallography

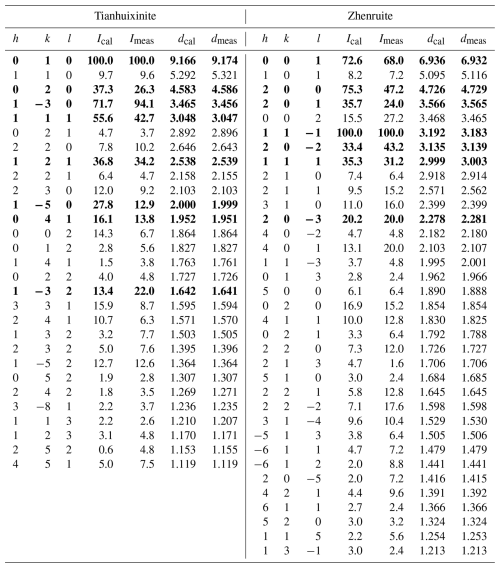

Both the powder and the single-crystal X-ray diffraction data for zhenruite and tianhuixinite were collected on a Rigaku Xtalab Synerg D/S four-circle diffractometer equipped with CuKα radiation (λ=1.54184 Å). Powder X-ray diffraction data were collected in the Gandolfi mode at 50 kV and 1 mA (Table 2), and the unit-cell parameters refined using the program by Holland and Redfern (1997) are a=9.6760(5), b=3.708(18), c=7.101(2) Å, β=102.372(1)°, and V=248.92(5) Å3 for zhenruite and a=10.5845(3), c=3.7285(1) Å, and V=361.74(2) Å3 for tianhuixinite.

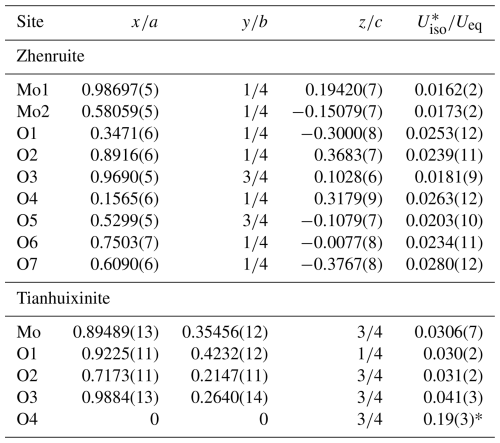

Table 4Fractional atomic coordinates and equivalent isotropic displacement parameters (Å2) for zhenruite and tianhuixinite.

Figure 8The crystal structure of zhenruite, (a) showing two kinds of topologically identical edge-sharing octahedral double chains extending along [010]: the type-A chain consisting of Mo1O6 octahedra only and the type-B chain consisting of Mo2O5(H2O) octahedra only. These two types of chains are linked together alternately through sharing corners (O6 atoms) to form layers parallel to (001). (b) The layers made of edge-sharing octahedral double chains are interconnected by hydrogen bonds along [001]. For clarity, possible hydrogen bonds are not drawn. The red and aqua spheres represent O and H2O, respectively. The figure was plotted using freeware VESTA (Momma and Izumi, 2011).

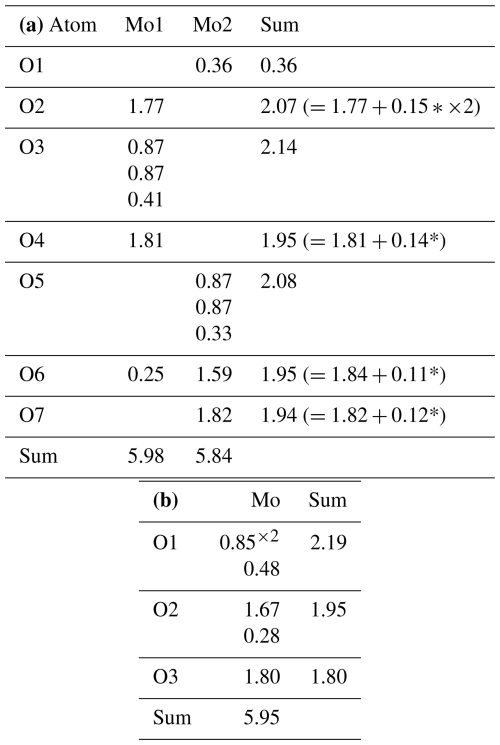

Table 7(a) Bond-valence sums () for zhenruite. (b) Bond-valence sums () for tianhuixinite.

* The valence values with an asterisk were calculated from the O⋯O distances using the parameters given by Ferraris and Ivaldi (1988) from the following possible hydrogen bonds: O1⋯O2 = 2.920 Å (×2), O1⋯O4 = 2.936 Å, O1⋯O6 = 3.160 Å, and O1⋯O7 = 3.050 Å.

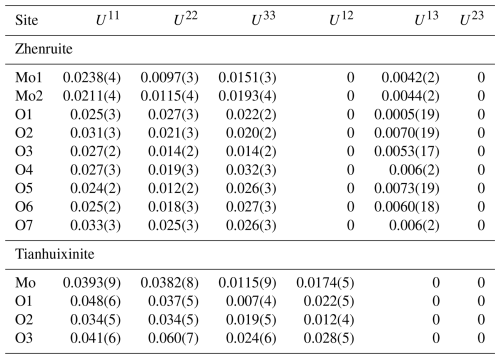

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data of zhenruite were collected from a µm fragment. All reflections were indexed on the basis of a monoclinic unit cell (Table 3). The systematic absences of reflections suggest possible space group P2 or P21. The crystal structure was solved and refined using SHELX2019 (Sheldrick, 2015a, b) based on space group P2 because it produced better refinement statistics in terms of bond lengths and angles, atomic displacement parameters, and R factors. The H sites could not be located through the difference Fourier syntheses. The positions of all atoms were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters. The final refinement statistics are listed in Table 3. Atomic coordinates and displacement parameters are given in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. Selected bond distances are presented in Table 6. The bond-valence sums (BVSs) were calculated using the parameters given by Ferraris and Ivaldi (1988) for O⋯O hydrogen bonds and by Brown (2009) for the rest (Table 7a).

For tianhuixinite, all crystals examined are multi-nanometric aggregates, making it very difficult to find a suitable single crystal for the structure determination. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data of tianhuixinite were collected from a µm fragment. All reflections were indexed on the basis of a hexagonal unit cell (Table 3). The systematic absences suggested possible space group P6 or P63. The crystal structure was solved and refined based on space group P6. The H sites could not be located through the difference Fourier syntheses. The positions of all atoms were refined with anisotropic displacement parameters, except for the O4 atom (the H2O molecule in the channel), which was refined isotropically because it exhibits abnormally large displacement parameters, especially along [001]. A similar result was also observed by Zhao et al. (2009) from their single-crystal X-ray structure analysis. Although our structure refinement suggested a possible splitting for the O4 site (at x=0, y=0, z=0.75) into two (one at x=0, y=0, z=0.9342 and the other at x=0, y=0, z=0.5658), a refinement with such a site-split model became unstable. Thus, the site-split model for the O4 atom was discarded. The final refinement statistics for tianhuixinite are listed in Table 3. Atomic coordinates and displacement parameters are given in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. Selected bond distances are presented in Table 6. The bond-valence sums were calculated using the parameters given by Brown (2009) (Table 7b).

3.1 Structure of zhenruite

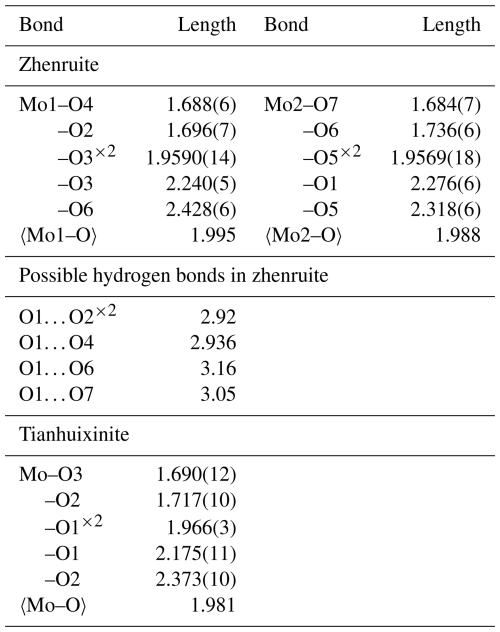

Zhenruite is the natural counterpart of synthetic (MoO3)2⋅H2O (Fellows et al., 1983; Bénard et al., 1994). Its crystal structure is characterized by two kinds of topologically identical octahedral double chains but with different compositions: the type-A chain consisting of edge-sharing Mo1O6 octahedra only and the type-B chain consisting of edge-sharing Mo2O5(H2O) octahedra only (Fig. 8a). These two types of chains extend along [010] and are linked together alternately through sharing corners (O6 atoms) to form layers parallel to (001) (Fig. 8a), which are interconnected by hydrogen bands along [001] (Fig. 8b).

Figure 9The crystal structure of tianhuixinite, showing (a) an edge-sharing (O1–O1) double chain of MoO6 octahedra along [001] and (b) the hexagonal channel formed by the double chains of MoO6 octahedra sharing corners, with H2O (O4) residing at the center of the channel. The figure was plotted using freeware VESTA (Momma and Izumi, 2011).

Both Mo1O6 and Mo2O5(H2O) octahedra in zhenruite are considerably distorted, with Mo–O bond lengths varying from 1.684 to 2.428 Å (Table 6). Each octahedron has two Mo–O bonds shorter than 1.74 Å, two between 1.95 and 1.96 Å, and two longer than 2.24 Å. Although our structure refinement did not locate H atoms, the calculated bond-valence sums (Table 7) clearly indicate that the O1 atom is the H2O molecule. An examination of O⋯O distances around O1 suggests the following possible hydrogen bonds: O1⋯O2 (=2.920 Å ×2), O1⋯O4 (=2.936 Å), O1⋯O6 (=3.160 Å), and O1⋯O7 (=3.050 Å). With these hydrogen bonds taken into account, the noticeable BVS deficiencies for O2, O4, O6, and O7 are significantly improved.

3.2 Structure of tianhuixinite

Tianhuixinite is the natural analogue of synthetic hexagonal P6 (MoO3)3⋅H2O, which was first synthesized by Rosenheim (1906) and later by numerous others (e.g., Garin and Blanc, 1983; Guo et al., 1994; Zhao et al., 2009; Lunk et al., 2010, and references therein). It should be pointed out that (MoO3)3⋅H2O also possesses an orthorhombic Aba2 polymorph with the unit-cell parameters a=7.3323(3), b=7.6901(3), c=12.6721(6) Å, and V=714.53 Å3 (Seguin et al., 1995). The crystal structure of tianhuixinite is composed of double chains of edge-sharing MoO6 octahedra extending along the c axis (Fig. 9a), which are corner-connected with one another to form hexagonal channels with H2O (O4) residing at the center of the channels (Fig. 9b). It is noteworthy that the octahedral double chains in zhenruite and tianhuixinite are topologically identical. As in zhenruite, the MoO6 octahedron in tianhuixinite is highly distorted in a similar fashion, with two Mo–O bonds shorter than 1.72 Å, two being 1.96 Å, and two longer than 2.18 Å.

In the MoO3–MoO3⋅2H2O system, six minerals have been documented to date, including molybdite MoO3, tianhuixinite (MoO3)3⋅H2O, zhenruite (MoO3)2⋅H2O, raydemarkite MoO3⋅H2O, virgilluethite MoO3⋅H2O, and sidwillite MoO3⋅2H2O. Structurally, these minerals can be divided into two groups. One group includes molybdite, tianhuixinite, zhenruite, and raydemarkite, all of which are built up from topologically identical double chains of edge-sharing MoO6 octahedra, although they may have different types of chains (type-A chains in molybdite and tianhuixinite, type-B chains in raydemarkite, and both types in zhenruite) and different linkages among the chains. Yang et al. (2023b) noted that zhenruite may be considered a combination of molybdite and raydemarkite both structurally and chemically, as depicted by Fig. 10. The other group includes sidwillite and virgilluethite, both of which are characterized by layers of corner-sharing MoO6 octahedra. The major structural difference between the two minerals is that sidwillite contains interlayer H2O molecules. Sidwillite can readily dehydrate to become virgilluethite by the loss of the interlayer H2O molecules, which has been demonstrated to take place between 60 and 80 °C through a topotactic mechanism (Günter, 1972; Boudjada et al., 1993).

Among four metastable polymorphs of MoO3 (β, β′, MoO3-II, and h-MoO3), the hexagonal P63/mh-MoO3 phase has attracted the most attention because, as compared to other polymorphs, it exhibits superior physical and chemical properties due to its three-dimensional framework with one-dimensional channels, which allows for a versatile intercalation chemistry with interesting chemical, electrochemical, electronic, and catalytic properties (e.g., Guo et al., 1994; Lunk et al., 2010; Kaur et al., 2021; Ghalehghafi and Rahmani, 2022; Li et al., 2024). Despite the long history of the h-MoO3 phase since its first synthesis over a century ago (Rosenheim, 1906) (see the thorough review on hexagonal molybdenum trioxide by Lunk et al., 2010), its crystal structure has only been correctly determined recently (e.g., Lunk et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2021; Li et al., 2024). The crystal structures of tianhuixinite and the h-MoO3 phase are topologically identical. The only difference is that the hexagonal channels in tianhuixinite contains H2O molecules, whereas those in h-MoO3 are empty. Nevertheless, as summarized by Lunk et al. (2010), a vast number of reported compounds synthesized in the MoO3–NH3–H2O system possess the hexagonal MoO3-type structure with the compositions varying from MoO3 and MoO3⋅0.33NH3 to MoO3⋅nH2O () and MoO3⋅mNH3⋅nH2O (; ). Accordingly, the discovery of tianhuixinite implies the likelihood of finding the ammonia analogue, MoO3⋅0.33NH3, in nature.

cif and checkcif files are available in the Supplement.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/ejm-38-39-2026-supplement.

XG: sample treatment, data analyses, and manuscript draft. HY: manuscript draft, data analyses. RG: provision of samples. GL: manuscript draft discussion.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We are grateful to Anthony Kampf and the anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments, which improved the quality of the paper.

This research has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 42072054).

This paper was edited by Sergey Krivovichev and reviewed by Anthony Kampf and one anonymous referee.

Andersson, G. and Magnéli, A.: On the crystal structure of molybdenum trioxide, Acta Chemica Scandinavica, 4, 793–797, 1950.

Bénard, P., Sequin, L., Louër, D., and Figlarz, M.: Structure of MoO3⋅1/2H2O by conventional X-ray powder diffraction, Journal of Solid State Chemistry, 108, 170–176, 1994.

Boudjada, N., Rodriguez-Carvajal, J., Anne, M., and Figlarz, M.: Dehydration of MoO3.2H2O: A neutron thermodiffractometry study, Journal of Solid State Chemistry, 105, 211–222, 1993.

Böschen, V. I. and Krebs, B.: Kristallstruktur der “weissen molybdänsäure” α-MoO3.H2O, Acta Crystallographica, B30, 1795–1800, 1974.

Bräkken, H.: Die kristallstrukturen der trioxyde von chrom, molybdän und wolfram, Zeitschrift für Kristallographie, 78, 484–488, 1931.

Brophy, G. P. and Kerr, P. F.: Hydrous uranium molybdate in Maryvale ore. in Annual Report for June 30, 1952 to April 1, 1953 RME-3046, U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, 45–51, 1953.

Brown, I. D.: Recent developments in the methods and applications of the bond valence model, Chem. Rev., 109, 6858–6919, 2009.

Čech, F. and Povondra, P.: Natural occurrence of molybdenum trioxide, MoO3, in Krupka (Molybdite, a new mineral), Acta Universitatis Carolinae – Geologica, 1, 1–14, 1963.

Césbron, F. and Ginderow, D.: La sidwillite, MoO3⋅2H2O; une nouvelle espèce minérale de Lake Como, Colorado, U.S.A. Bulletin de Minéralogie, 108, 813–823, 1985.

Cunningham, C. G., Rasmussen, J. D., Steven, T. A., Rye, R. O., Rowley, P. D., Romberger, S. B., and Selverstone, J.: Hydrothermal uranium deposits containing molybdenum and fluorite in the Marysvale volcanic field, west-central Utah, Mineralium Deposita, 33, 477–494, 1998.

de Castro, I. A., Datta, R. S., Ou, J. Z., Castellanos-Gomez, A., Sriram, S., Daeneke, T., and Kalantar-zadeh, K.: Molybdenum Oxides – From Fundamentals to Functionality, Advanced Materials, 28, 1701619, https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201701619, 2017.

Deki, S., Béléké, A. B., Kotani, Y., and Mizuhata, M.: Liquid phase deposition synthesis of hexagonal molybdenum trioxide thin films, Journal of Solid State Chemistry, 182, 2362–2367, 2009.

Fellows, R. L., Lloyd, M. H., Knight, J. F., and Yakel, H. L.: X-ray diffraction and thermal analysis of molybdenum(VI) oxide hemihydrate: monoclinic MoO3⋅1/2H2O, Inorganic Chemistry, 22, 2468–2470, 1983.

Ferraris, G. and Ivaldi, G.: Bond valence vs bond length in O⋯O hydrogen bonds, Acta Crystallographica, B44, 341–344, 1988.

Fu, G., Xu, X., Lu, X., and Wan, H.: Mechanisms of Methane Activation and Transformation on Molybdenum Oxide Based Catalysts, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 127, 3989–3996, 2005.

Garin, J. L. and Blanc, J. M.: Refinamiento de la estructura cristalina del NH3(MoO3)3, Contribuciones Cientificas y Technologicas, 13, 43–55, 1983.

Ghalehghafi, E. and Rahmani, M. B.: Hydrothermal temperature effect on the growth of h-MoO3 thin films using seed layers and their photoluminescence properties, Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing, 137, 106243, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2021.106243, 2022.

Günter, J. R.: Topotactic dehydration of molybdenum trioxide-hydrates, Journal of Solid State Chemistry, 5, 354–359, 1972.

Guo, J., Zavalij, P., and Whittingham, M. S.: Preparation and characterization of a MoO3 with hexagonal structure, European Journal of Solid State and Inorganic Chemistry, 31, 833–842, 1994.

Holland, T. J. B. and Redfern, S. A. T.: Unit cell refinement from powder diffraction data: the use of regression diagnostics, Mineralogical Magazine, 61, 65–77, 1997.

Kaur, J., Kaur, K., Pervaiz, N., and Mehta, S. K.: Spherical MoO3 nanoparticles for photocatalytic removal of eriochrome black T, ACS Applied Nano Materials, 4, 12766–12778, 2021.

Kihlborg, L.: Least squares refinement of the crystal structure of molybdenum trioxide, Arkiv för Kemi, 21, 357–364, 1963.

Krebs, B.: Die kristallstruktur von MoO3⋅2H2O, Acta Crystallographica, B28, 2222–2231, 1972.

Li, L., Zhao, Y., Wang, J.J., Cui, R., Li, Y., Qi, L., and Dang, D.: Hexagonal phase MoO3 with three-dimensional crystal structure as heterogeneous photocatalyst for tetracycline degradation: Degradation pathways and mechanism, Journal of Molecular Structure, 1295, 136681, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molstruc.2023.136681, 2024.

Lindqvist, I.: The crystal structure of the yellow molybdic acid, MoO3⋅2H2O, Acta Chemica Scandinavica, 4, 650–657, 1950.

Liu, D., Lei, W. W., Hao, J., Liu, D. D., Liu, B. B., Wang, X., Chen, X. H., Cui, Q. L., Zou, G. T., Liu, J., and Jiang, S.: High-pressure Raman scattering and x-ray diffraction of phase transitions in MoO3, J. Appl. Phys., 105, 023513, https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3056049, 2009.

Lunk, H. J., Hartl, H., Hartl, M. A., Fait, M. J., Shenderovich, I. G., Feist, M., Frisk, T. A., Daemen, L. L., Mauder, D., Eckelt, R., and Gurinov, A. A.: “Hexagonal molybdenum trioxide” – known for 100 years and still a fount of new discoveries, Inorganic Chemistry, 49, 9400–9408, 2010.

Mandarino, J. A.: The Gladstone–Dale relationship. IV. The compatibility concept and its application, Canadian Mineralogist, 19, 441–450, 1981.

McCarron, E. M.: β-MoO3: a metastable analogue of WO3, Journal of the Chemical Society, Chemical Communications, 1986, 336, https://doi.org/10.1039/C39860000336, 1986.

McCarron, E. M. and Calabrese, J. C.: The growth and single crystal structure of a high pressure phase of molybdenum trioxide: MoO3-II, Journal of Solid State Chemistry, 91, 121–125, 1991.

McLemore, V. T., Donahue, K., Breese, M., Jackson, M. L., Arbuckle, J., and Jones, G.: Mineral resource assessment of Luna County, New Mexico, New Mexico Bureau of Geology and Mineral Resources Open-file Report OF-459, 85 pp., 2001.

Momma, K. and Izumi, F.: VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data, Journal of Applied Crystallography, 44, 1272–1276, 2011.

Mougin, O., Dubois, J., and Mathieu, F.: Metastable Hexagonal Vanadium Molybdate Study, Journal of Solid State Chemistry, 152, 353–360, 2000.

Oswald, H. R., Gunter, J. R., and Dubler, E.: Topotactic decomposition and crystal structure of white molybdenum trioxide-monohydrate: Prediction of structure by topotaxy, Journal of Solid State Chemistry, 13, 330–338, 1975.

Parise, J. B., McCarron, E. M., Dreele, R. V., and Goldstone, J. A.: β-MoO3 produced from a novel freeze drying route, Journal of Solid State Chemistry, 93, 193–201, 1991.

Rosenheim, A. and Davidsohn, I.: Die hydrate der molybdänsäure, Zeitschrift für Anorganische und Allgemeine Chemie, 37, 314–325, 1903.

Rosenheim, A. Z.: Die Darstellung von Molybdansauredihydrat, Zeitschrift für Anorganische Chemie, 50, 320–320, 1906 (in German).

Schultén, A. B. A.: Recherches sur l'arséniate dicalcique, Reproduction artificielle de la pharmacolite et de la haidingerite, Bulletin de Minéralogie, 26, 18–24, 1903.

Seguin, L., Figlarz, M., Cavagnat, R., and Lasskgues, J.-C.: Infrared and Raman spectra of MoO3, molybdenum trioxides and MoO3⋅xH2O molybdenum trioxide hydrates, Spectrochimica Acta Part A, 51, 1323–1344, 1995.

Sheldrick, G. M.: SHELXT – Integrated space-group and crystal structure determination, Acta Crystallographica A71, 3–8, 2015a.

Sheldrick, G. M.: Crystal structure refinement with SHELX, Acta Crystallographica, C71, 3–8, 2015b.

Simmons, P.: Cookes Peak Mining District, Luna County, New Mexico, Rocks Miner., 94, 214–239, 2019.

Sitepu, H.: Texture and structural refinement using neutron diffraction data from molybdite (MoO3) and calcite (CaCO3) powders and a Ni-rich Ni50.7Ti49.30 alloy, Powder Diffraction, 24, 315–326, 2009.

Wang, S. Y., Dong, X., and Zhou, Z. H.: Novel isopolymolybdates with different configurations of hexagram, double dish, and triangular dodecahedron, Journal of Solid State Chemistry, 300, 122229, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssc.2021.122229, 2021.

Wooster, N.: The crystal structure of Molybdenum Trioxide, MoO3, Zeitschrift für Kristallographie, 80, 504–512, 1931.

Yang, H., Gu, X., Gibbs, R. B., and Downs, R. T.: Virgilluethite: a new mineral and the natural analogue of synthetic β-MoO3⋅H2O, from Cookes Peak, Luna County, New Mexico, USA, Can. J. Miner. Petrol., 61, 1151–1162, 2023a.

Yang, H., Gu, X., Sousa, F. X., Gibbs, R. B., McGlasson, J. A., and Downs, R. T.: Raydemarkite, the natural analogue of synthetic α-MoO3⋅H2O, from Cookes Peak, Luna County, New Mexico, U.S.A, Can. J. Miner. Petrol., 61, 203–213, 2023b.

Zhao, J., Ma, P., Wang, J., and Niu, J.: Synthesis and structural characterization of a novel three-dimensional molybdenum–oxygen framework constructed from Mo3O9 units, Chem. Lett., 38, 694–695, 2009.