the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Exploring the unusual occurrence, chemistry, and structural topology of åsgruvanite-(Ce), Ce16Ca5Al(SiO4)6(AsO3)8(CO3)2Cl3(ClF3)(OH)2, a new rare earth element (REE) mineral from Västmanland, Sweden

Alice Taddei

Erik Jonsson

Hans-Jürgen Förster

Stefan S. Andersson

Oona Appelt

Luca Bindi

Åsgruvanite-(Ce), ideally Ce16Ca5Al(SiO4)6(AsO3)8(CO3)2Cl3(ClF3)(OH)2, is a new mineral species (IMA–CNMNC 2025-004) from the Åsgruvan Fe-skarn deposit, Norberg, Västmanland, Sweden, which is directly related to the Bastnäs type of rare earth element (REE) mineralisations in the Palaeoproterozoic Bergslagen ore province. Åsgruvanite-(Ce) occurs as anhedral, occasionally elongated grains up to 400 µm. It is greyish green to nearly colourless, with a white streak and a vitreous to greasy lustre. Cleavage is distinct on {001} and less so on {100}; the mineral is brittle, and its fracture is uneven. The calculated density is 4.79(1) g cm−3. Åsgruvanite-(Ce) is optically uniaxial (+), with a refractive index above 1.8; the calculated average is 1.88 (Gladstone–Dale approach). Åsgruvanite-(Ce) crystallises in the trigonal system in space group P-3m1 (Z=1), with the following unit cell parameters: a=10.5728(6) Å and c=15.0899(11) Å. Åsgruvanite-(Ce) occurs in a magnetite–REE skarn, but its formation postdates the groundmass carbonate and skarn assemblage, and it is associated with late-stage calcite, dolomite, a dollaseite-like allanite group mineral, gadolinite-(), and a fluorocarbonate related to bastnäsite-(Ce), with variable F contents. The structure was refined to R1=6.23 % for 987 reflections. It is unique and consists of two alternating layers, A and B, along the c axis. Layer A (∼8.4 Å) has the composition [(Ce12Ca3)AlSi6(C1.50S0.50)Σ2.00O30(OH)2]15+. Layer B (∼6.7 Å) corresponds to the composition [(Ce4Ca2)AsO24Cl4F3]15−. These layers form tunnel-like features parallel to [100], which are partially occupied by Cl atoms. Spectroscopic data (infrared and micro-Raman) support the structural model.

- Article

(11838 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(178 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

In the course of the scientific description of arrheniusite-(Ce) from the Östanmossa mine, Norberg, Västmanland, Sweden (Holtstam et al., 2021b), a potentially new mineral with essential rare earth elements (REEs) was observed as minute grains sized 10–40 µm. It was shown to contain a unique set of combinations of elements: Si, As, Ca, Ce, La, Nd, Y, O, F, and Cl, as well as other minor components. The rarity and small size of the grains precluded a detailed study at the time. However, a serendipitous find of a mineral with a very similar composition but occurring in larger crystals (Andersson et al., 2024) in the nearby mine Åsgruvan, Norberg, Västmanland, Sweden (lat. 60°4′50′′ N, long. 15°56′25′′ E; Fig. 1) made a full description possible.

Here, we present the new species, åsgruvanite-(Ce), recently approved by IMA-CNMNC (no. 2025-004); the recommended mineral symbol is Åsg-(Ce). It is named after the type locality, Åsgruvan, meaning the “Ås mine” in Swedish; the term “Ås” is often used for a ridge or an esker. The letter Å (å) is separate letter from A (a) in the Swedish alphabet and is sounded out as [o:] in IPA notation; the mine's name is thus pronounced [o:sgru:van]. Cerium is the dominant REE, indicated by the suffix “-(Ce)”.

The greater part of the holotype material, including the crystal used for crystallographic and chemical studies, is deposited in the type mineral collection of the Department of Geosciences, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm, Sweden, under the collection no. GEO-NRM #20240017.

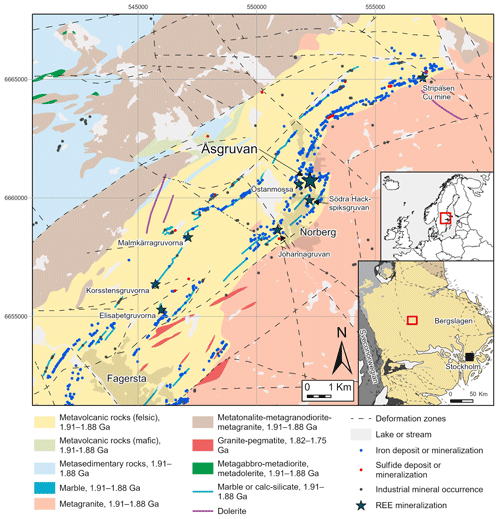

Figure 1Bedrock geological map of the Fagersta–Norberg area of Bergslagen, with mineralisations and deposits indicated. REE-enriched deposits are marked with stars. The inset map (lower right) shows the lithotectonic units and deformation zones of the south-central part of Sweden, as indicated in the smaller overview map of northern Europe. The geological maps are based on the datasets of the Geological Survey of Sweden (SGU, Sveriges Geologiska Undersökning).

Åsgruvanite-(Ce) was discovered in a sample (original dimensions of ca. cm) collected in 1931 at the 130 m level of the mine. Åsgruvan is a magnetite-skarn deposit situated in the Palaeoproterozoic Bergslagen ore province in south-central Sweden (Fig. 1). The Åsgruvan and the nearby Östanmossa deposits are directly related to the Bastnäs-type REE deposits in the province (e.g. Geijer, 1961; Holtstam and Andersson, 2007; Jonsson et al., 2019; Andersson et al., 2024). The province is known for its abundance of mineralisation, predominantly of iron oxides and base metal sulfides but also of noble metals, manganese, and tungsten, in addition to REEs. It constitutes the oldest of the major ore provinces in the country with regard to mining. In particular, the Norberg area was a long-standing mining centre, with over 600 mines, bigger and smaller, registered within the greater Norberg area (Sädbom, 2015). Iron mining in the Norberg district began in the Middle Ages (Bindler et al., 2011) and continued until the early 1980s; the Åsgruvan mine was worked for Mn-poor Fe ore down to ∼222 m from about 1880 until 1964 (Hopsu, 1992).

The majority of mineralisations in the ore province are primarily hosted by a ca. 1.91–1.88 Ga Svecofennian metasupracrustal succession, most importantly comprising felsic (rhyolitic to dacitic) metavolcanic rocks with intercalated, often skarn-altered marbles, interpreted to have originally formed in a continental back-arc setting (Allen et al., 1996). Essentially, syn-volcanic to younger intrusive rocks of mainly a granitoid character, with minor mafic units, intruded into this metasupracrustal package and constitute large volumes of the presently exposed bedrock in Bergslagen, including the Norberg area (Fig. 1). The REE-enriched Fe-skarn deposits of Bastnäs type occur along an over 100 km long belt of variably marble-bearing, felsic metavolcanic rocks known as the “REE line”, stretching from Nora in the southwest via Bastnäs to (and beyond) the Norberg area in the northeast (e.g. Andersson et al., 2024, and references therein). Polyphase regional metamorphism of greenschist to upper amphibolite facies grade during the ca. 1.90–1.80 Ga Svecokarelian orogeny, together with associated ductile to brittle deformation, has variably affected all of the older rocks in the province, as well as their mineralisations.

The Åsgruvan skarn deposit is situated within a stratified metavolcanic sequence intercalated with horizons of skarn-altered calcite–dolomite marbles and quartz-rich iron ores (Geijer 1936). It represents the same folded ore-bearing horizon as the nearby Östanmossa deposit. The major skarn assemblages are pyroxene–clinoamphibole–garnet and magnetite (Sarap, 1957). Specifically, the ore-bearing skarn is dominated by diopside-rich pyroxene and actinolite and can locally contain abundant andradite (Geijer, 1936; Magnusson, 1973). REE mineralisation in the Åsgruvan skarn was first reported by Geijer (1936), who described it as sparse but locally enriched at the 130 m level. A notable occurrence includes a zone at least 5 m long and 15 cm wide at the contact between the skarn zone and a dolomitic marble, consisting of “magnesium orthite” mixed with magnetite, tremolite, “serpentine”, and fluorite. Additionally, disseminated magnesium orthite also occurred in the actinolite-dominated skarn (Geijer, 1936). REE mineralisation was later also found at deeper levels in the mine (Geijer and Magnusson, 1944). Subsequent studies of material originally collected by Per Geijer identified the presence of a dollaseite-like allanite group mineral, having dominant Mg at both the M1 and M3 sites with only minor detected F, gadolinite-(Y), and bastnäsite-(Ce) but also subordinate synchysite-(Ce), monazite-(Ce), and fergusonite-(Y), as well as the presently described mineral (Andersson et al., 2024). The cerite originally reported by Geijer (1936) could not be verified.

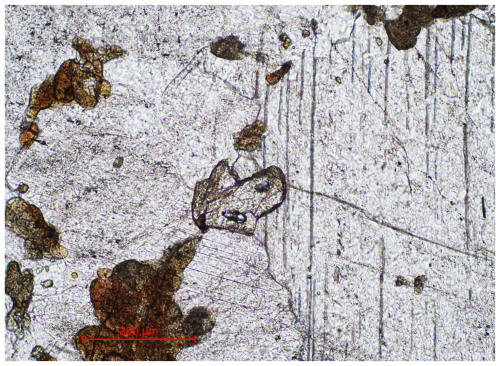

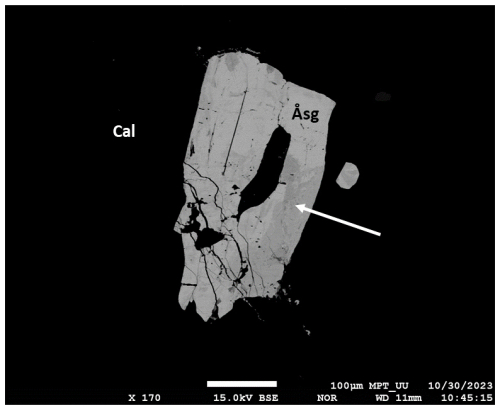

Figure 2Transmitted-light microscopy image in plane-polarised light of near-colourless åsgruvanite-(Ce) with high optical relief (centre) in calcite matrix. Pleochroic aggregates in brownish hues are composed of the dollaseite-like allanite group mineral.

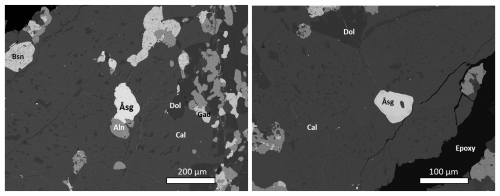

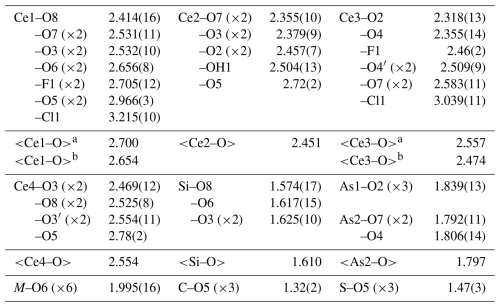

Figure 3SEM-BSE images of a polished section in epoxy mount. Symbols: Åsg – åsgruvanite-(Ce); Aln – a potential member of the allanite subgroup (the dollaseite-like mineral); Gad – gadolinite-(Y); Cal – calcite; Bsn – fluorocarbonate related to bastnäsite, with variable F contents (possibly a bastnäsite–hydroxylbastnäsite solid solution). The darkest grains are dolomite (Dol). The crystal in the image to the left was used for chemical, spectroscopic (FTIR), and structural determinations. The image to the right shows a partly altered grain of åsgruvanite-(Ce) (with a tiny inclusion of calcite), from which Raman spectroscopy data were collected as well. The dark spot at the centre of the grain is, possibly, a carbonate.

Figure 4SEM-BSE image of a large (ca. 400 µm) åsgruvanite-(Ce) crystal (Åsg), with altered portions (white arrow) and fractures. Black areas on the image are calcite (Cal).

Åsgruvanite-(Ce) occurs as rare, isolated grains in a calcite-dominated matrix (Figs. 2–4) and very rarely as inclusions in gadolinite-(Y). Notably, the calcite hosting the new mineral is relatively coarse-grained compared to abundant groundmass carbonates and appears as infillings of cross-cutting fractures; i.e. it is younger than the groundmass carbonates and skarn assemblages. The new mineral often appears to be contiguous in relation to grains of the dollaseite-like allanite group mineral of complex composition (Fig. 3a). It essentially belongs to the dollaseite–ferriallanite-(Ce) compositional space, together with a component possibly representing the OH analogue of dollaseite-(Ce) (see Taddei et al., 2025). Some åsgruvanite-(Ce) crystals are affected by alteration, visible as darker domains and rims in the back-scattered electron (BSE) image (Figs. 3b–4). Alteration-induced changes in composition include the depletion of Cl and a concomitant enrichment in F, together with the loss of Ca. Lower analytical totals suggest the uptake of H2O. The mineral assemblage in the skarn sample identified so far includes calcite, dolomite, tremolite, phlogopite, magnetite, fluorite, bastnäsite-(Ce)–hydroxylbastnäsite-(Ce), synchysite-(Ce), gadolinite-(Nd), gadolinite-(Y), the dollaseite-like allanite group mineral, monazite-(Ce), fergusonite-(Y), pyrite, chalcopyrite, molybdenite, löllingite, and scheelite.

Åsgruvanite-(Ce) forms anhedral grains, occasionally elongated, up to 400 µm in their greatest dimension. The colour is greyish green to almost colourless; the streak is white. Åsgruvanite-(Ce) is vitreous to greasy in lustre. Hardness (Mohs) is estimated to be 4–5 from the polishing hardness. Cleavage is noted to be distinct on {001} and less developed on {100}. The mineral is brittle with an uneven fracture. The density was not measured because of the minute size of the available grains. The value 4.79(1) g cm−3 was calculated using the empirical chemical formula and unit cell volume from single-crystal X-ray diffraction data (vide infra).

Optically, åsgruvanite-(Ce) is uniaxial (+): the refractive index n is higher (>1.8) than that of available refraction liquids; the average ncalc=1.88 from Gladstone–Dale constants (Mandarino, 1981), as is also evident from its high optical relief (Fig. 2). Pleochroism is very weak, colourless to faint green, and the birefringence is high. In reflected polarised light, åsgruvanite-(Ce) is the most reflective (∼10 %) REE mineral in polished sections compared to gadolinite-(Nd), the dollaseite-like allanite group mineral, etc.

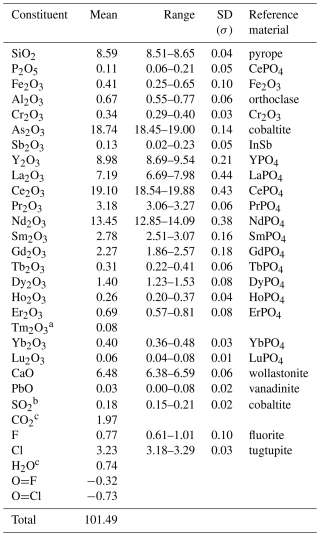

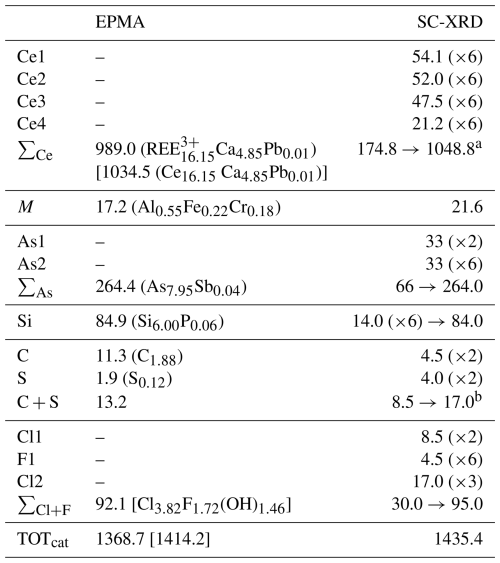

Table 1Chemical data (in wt %) for åsgruvanite-(Ce) from the crystal used for SC-XRD.

a Tm content calculated by interpolation between chondrite-normalised abundances of Er and Yb. b Assumed to be S4+ based on the geometry of the hosting site according to the structural data. c Calculated from structural formula, i.e. (Cl + F + OH) = 9 apfu and (C + S) = 2 apfu.

Results from chemical micro-analyses by means of an electron microprobe (EMPA) in wavelength dispersion mode (WDS; a Jeol JXA-8230 Superprobe with tungsten or LaB6 cathodes) at 20 kV acceleration voltage, 10 nA beam current, and 2 µm beam size are reported in Table 1. The total number of spot analyses on a single crystal (later used for the X-ray diffraction and spectroscopic analyses) was 15. The following elements were searched for but found to be below the limit of detection: Mg, Br, Ti, and Na. Nitrogen was detected at 0.01 wt %–0.03 wt %. The contents of H2O and CO2 were not determined directly because of a dearth of material but were inferred from the crystal structure and vibrational spectra (vide infra).

The empirical chemical formula of åsgruvanite-(Ce), based on 38 cations, with C calculated from (C + S) = 2 apfu (atoms per formula unit) and OH from (Cl + F + OH) = 9 apfu, can be written as follows: [(Ce4.89Nd3.36Y3.34La1.84Pr0.81Sm0.67Gd0.53Dy0.32Er0.15 Yb0.08Tb0.07Ho0.06Tm0.02Lu0.01)Σ16.15 Ca4.85Pb0.01]Σ21.01(Al0.55Fe0.22Cr0.18)Σ0.95(Si6.00P0.06)Σ6.06 (AsSb)Σ7.99(C1.88S)Σ2 O54[(Cl3.82F0.18)Σ4(F1.54OH1.46)Σ3(OH)2]Σ9. The ideal chemical formula of åsgruvanite-(Ce) is Ce16Ca5Al(SiO4)6(AsO3)8(CO3)2Cl3(ClF3)(OH)2, which requires Ce2O3 60.25, CaO 6.43, Al2O3 1.17, SiO2 8.27, As2O3 18.16, CO2 2.02, Cl 3.26, F 1.31, H2O 0.41, Cl ≡ O –0.73, F ≡ O –0.55, and a total of 100 wt %.

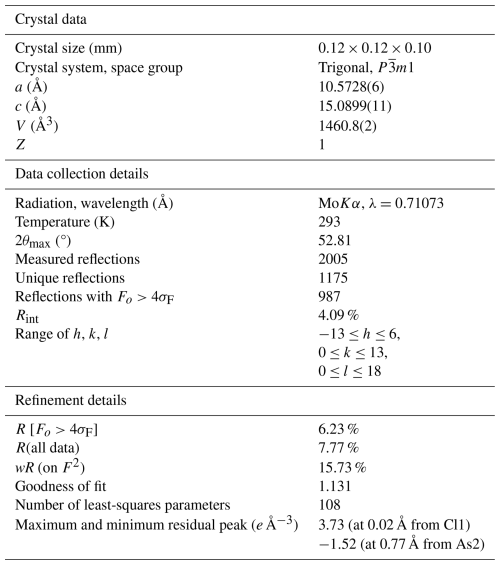

5.1 Single-crystal data

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SC-XRD) studies were carried out with a Bruker D8 Venture diffractometer equipped with a Photon III detector. The SC-XRD data were collected using graphite-monochromatised MoKα radiation (λ=0.71073 Å). The detector-to-crystal distance was 40 mm. Data were collected using ω and φ scan modes, with an exposure time of 15 s per frame. A total of 570 frames was collected. The frames were integrated with the Bruker SAINT software package using a narrow-frame algorithm. The intensity data were corrected for Lorentz and polarisation effects and for absorption (multi-scan method) with the APEX5 software suite (Bruker, 2023). Refined unit cell parameters with the other crystal data and experimental conditions are summarised in Table 2. A total of 1175 unique reflections were collected, and an inversion centre was indicated by statistical tests on the distribution of values (). No systematic absences were observed, and the space group was chosen (Rint=4.1 %). The structure was solved by means of direct methods and refined to R1 = 6.23 % for 987 unique reflections with I>2σ(I) using the programs SHELXT and SHELXL (Sheldrick, 2015), respectively. Final atom coordinates and equivalent isotropic displacement parameters are given in Table 3, while selected interatomic distances are listed in Table 4. A crystallographic information file (CIF) is available as a Supplement.

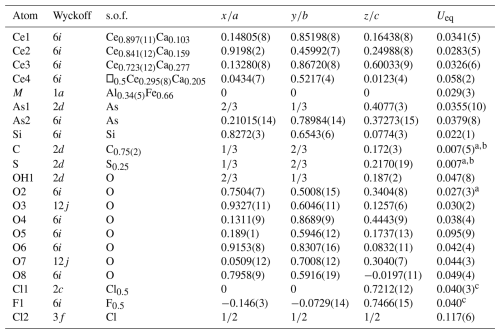

Table 3Atomic coordinates, site occupancy factors (s.o.f.'s), and equivalent isotropic parameters (Å2) for åsgruvanite-(Ce).

a Uiso; b, c restrained to be equal.

Table 4Selected interatomic distances (Å) for åsgruvanite-(Ce).

a If Cl1 is involved; b if F1 is involved. Note that, for the As4 tetrahedra shown in Fig. 8, the As–As distance is 3.9 Å, significantly longer than in bonded As4 (2.4 Å).

The initial structure solution yielded the positions of Ce1, Ce2, Ce3, Si, As1, As2, and the oxygen atoms from O1 to O6, while the positions of the remaining atoms were determined through a three-dimensional ΔF synthesis. The structure was then refined. Site occupancy factors (s.o.f.'s) were refined using the scattering curves for neutral atoms from the International Tables for Crystallography (Wilson, 1992).

The crystal structure of åsgruvanite-(Ce) shows no relation to other known compounds. As shown in Table 3, there are four distinct cation sites hosting mixed REE–Ca atoms, one of which (Ce4) is half-occupied due to stereochemical constraints (the Ce4–Ce4 bond distance, 0.878 Å, is too short to permit full occupancy): two are As3+ trigonal pyramids, one is an isolated Si tetrahedron, and one is an M octahedron. In addition, two split sites were observed: the first one displays a trigonal–pyramidal coordination when it hosts S (∼25 %) or a triangular–planar coordination when it hosts C (∼75 %). The second split site hosts anions, namely 50 % Cl and 50 % F. In this case, the splitting involves different Wyckoff positions with different multiplicities; of course, both C and S and Cl and F are mutually exclusive as, if present simultaneously, they would be too close to each other. Given the presence of a half-occupied site (Ce4) and other disorder in the structure (as evidenced by the two split sites described above), the crystal was re-checked by means of SC-XRD with longer exposure times, but neither superstructure reflections nor weak, diffuse scatterings were detected. Furthermore, alternative space groups – both centrosymmetric () and non-centrosymmetric (P3 and P3m1) – were tested (also taking into account the presence of merohedric twinning for acentric groups; see below) but did not yield significant differences or highlight specific inconsistencies.

It is worth noting that the acentric structural models we obtained did show high values in the correlation matrix between pairs of atoms which are equivalent in the centrosymmetric space group . However, to further test whether the acentric model had to be preferred to the centric one, we also tested the presence of twinning by inversion in the non-centrosymmetric structure refinement. Indeed, as is well known, a centrosymmetric structure that is refined as non-centrosymmetric will show a twin scale factor, equivalent to the Flack parameter in the case of inversion twinning (Flack et al., 2006; Müller et al., 2006), that refines to 50 % within analytical uncertainty. We found the racemic twin-component scale factor to be refined to 0.48(2), inconsistently with a highly asymmetrical distribution of the enantiomorphic components and indicating the centric model as the correct choice.

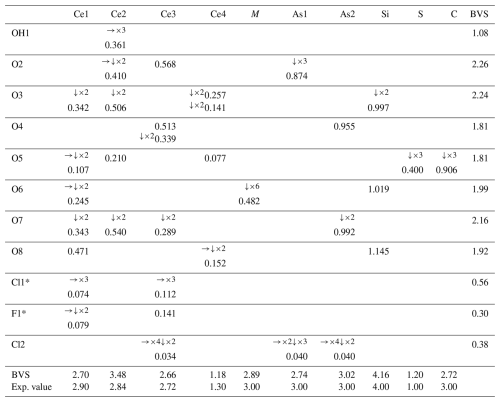

Table 5Bond valences (in valence units) calculated with the parameters given by Brese and O'Keeffe (1991) for åsgruvanite-(Ce).

* Split site: if Cl1 occurs, F1 does not – this BVS must be, collectively, close to 1.00 (0.86). The populations for the Ce sites only consider Ce3+ among REE3+. The populations used to calculate the BVSs are those obtained from the structure refinement (Table 3).

The formula obtained from the structural model, (CeCa4.46□3)Σ24(Al0.34Fe)Σ1Si6As(C1.5S0.5)Σ2 O54[Cl3(Cl□)(F3□3)(OH)2]Σ13, is in fairly good agreement with the empirical formula obtained from microprobe data.

Table 5 contains the bond-valence sums (BVSs), from which it was possible to infer the presence of OH at one of the eight oxygen positions (OH1). To further support the presence of (OH) at this site, the ΔF map was checked: one of the residues, distant 0.98 Å from OH1 (Wyckoff 2d, , , 0.1189), was tentatively modelled by fixing its coordinates, s.o.f., and displacement parameter. Assuming this as the H site, the OH bridge would involve O1 and O3, with O1–O3 = 2.997(18) Å. Nevertheless, the site was not included in the final model as the z coordinate changed to an unlikely value when left free to vary (leading to an A alert, code PLAT975_ALERT_2_A). Other problems (A alert, code PLAT971_ALERT_2_A) could be linked to a disorder located at the chlorine position. The BVS also highlighted a rather large discrepancy for Ce2 as the sum at this site was calculated assuming Ce as the only REE; this discrepancy could be explained if one assigns a substantial amount of Y at this site. For instance, assuming that Ce2 hosts 85 % Y and 15 % Ca, the resulting BVS would be 2.8 vu, which is closer to the expected value of 2.84 vu, and the values of the coordinated oxygen atoms would also improve. Lastly, Table 6 shows the comparison between the electron numbers obtained from microprobe data and those calculated from the structural model.

Table 6Comparison between the site scattering (per site → total) from microprobe data and from the structural refinement.

a Calculated considering Ce3+ only. b The relatively large discrepancy (4 e−) could be due to an incorrect ratio as carbon was only inferred and not measured by an electron microprobe.

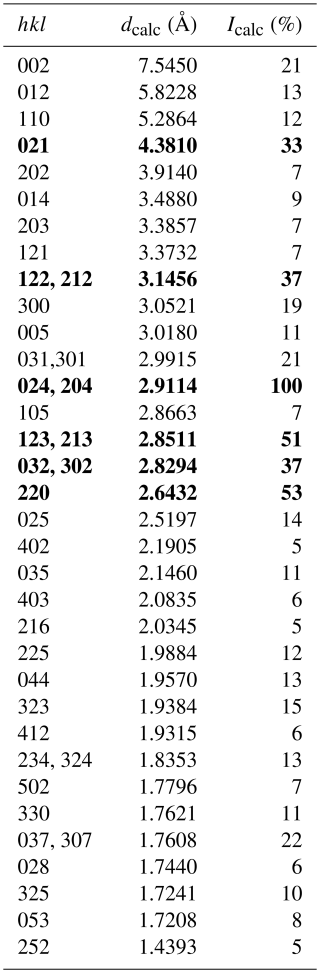

Table 7Calculated X-ray powder diffraction data (d in Å) for åsgruvanite-(Ce). The strongest Bragg reflections are given in bold.

Note that only reflections with Icalc>5 % are listed. The calculated diffraction pattern is obtained with the atomic coordinates and site occupancies reported in Table 3.

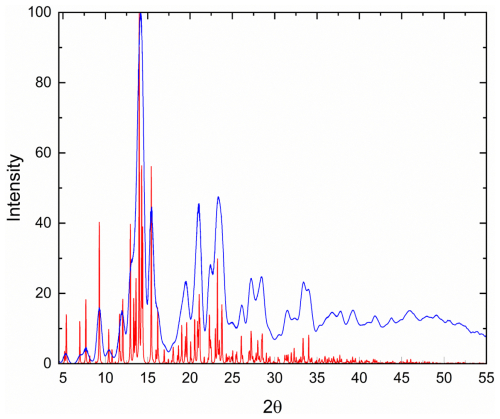

5.2 Powder data

Given the heterogeneity of the material studied, X-ray powder diffraction data (Table 7) were calculated from the structural model; a comparison between the calculated pattern and the pattern obtained by collapsing single-crystal X-ray diffraction data (λ=0.71073) into two dimensions using the software Platon (Spek, 2009) is reported in Fig. 5, showing no significant deviations between the two patterns.

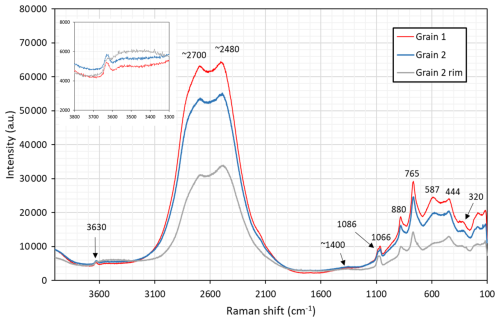

6.1 Raman micro-spectroscopy

Raman spectra of åsgruvanite-(Ce) were collected on two grains using a LabRAM HR 800 micro-spectrometer, with a 515 nm continuous-wave single-frequency diode-pumped laser (Cobolt Fandango 25 mW), a Peltier-cooled (−70 °C) charge-coupled device detector (Synapse), and an Olympus MPlan N objective. The instrument was calibrated against the 521 nm Raman band of silicon before the sample measurement. A filter allowing laser throughput of 10 % was employed, with the laser spot on the polished sample surface being ∼2 µm in diameter. Instrument control and data acquisition (200 s in two cycles with a 600 grooves cm−3 grating) were made with the LabSpec 6 software.

The obtained spectra (Fig. 6) are heavily influenced by fluorescence between 2000 and 3000 cm−1. The most prominent peaks of other regions are interpreted as follows: 1086, 1066 cm−1 symmetric stretching of C–O bonds; 880 cm−1 Si–O stretching; 765 cm−1 As3+–O stretching; 587 cm−1 Si–O bending; and 444, 320 cm−1 metal–O vibrations. Specifically, the band at 765 cm−1 is diagnostic with respect to arsenite groups (Bahfenne et al., 2012; Holtstam et al., 2021a), in contrast to arsenate, for which the As5+–O symmetric stretch is manifested with bands >800 cm−1 (Frost and Kloprogge, 2003). The very weak (broad) feature at ca. 1400 cm−1 relates to asymmetric stretching of CO3 groups. The weak band at 3630 cm−1 originates from O–H stretching modes, and this value would correspond to a long OH…O bridge, ≥3 Å, according to the empirical correlations found by Libowitzky (1999).

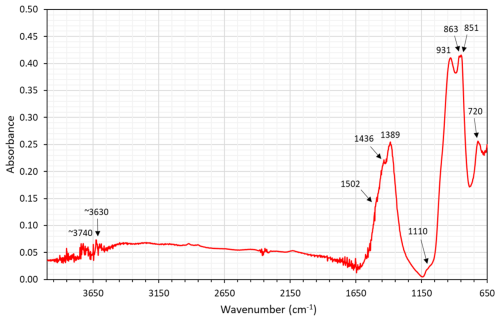

6.2 Infrared spectroscopy

A Fourier transform-infrared (FTIR) spectrum (Fig. 7) was acquired on the X-rayed (see below) crystal embedded in a polished epoxy mount by means of a Nicolet RaptIR microscope attached to a Nicolet iS50 FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Fisher). The instrument is equipped with a Polaris IR source, a KBr beam splitter, and a liquid-nitrogen-cooled MCT detector. The spectrum was collected in micro-attenuated total reflectance (mATR) mode, employing a Ge tip, adjusting the aperture size to that of the crystal. A total of 64 scans were averaged for the spectrum, with a spectral range between 4000–650 cm−1 and a resolution of 4 cm−1. The data were analysed with the OMNIC Paradigm software.

Observed bands at 1436 and 1389 cm−1 are interpreted as emanating from C–O stretching of carbonate groups (ν3 mode), whereas the bands at 863–851 cm−1 (ν2) and 720 cm−1 (ν4) represent deformation modes (see Farmer, 1974). The presence of satellite bands could be related to positional disorder or site-splitting. Bands in the region of 1000–900 cm−1 are likely to be related to Si–O vibrations. In the region above 3500 cm−1, the spectrum of åsgruvanite-(Ce) is affected by instrumental noise due to the mATR technique employed and the reduced spectral range observable through the Ge tip, but signals from OH vibrations are still detectable at ∼3630 and ∼3740 cm−1.

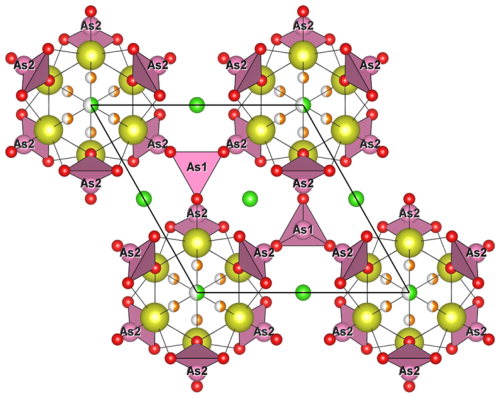

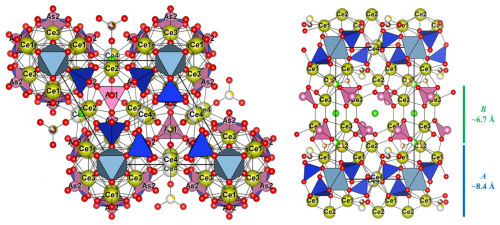

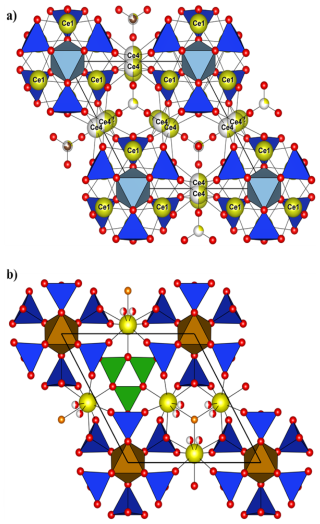

Figure 8Crystal structure of åsgruvanite-(Ce). On the left is the projection down [001], and on the right is the projection down [100], showing the A (blue) and B (green) layers. Symbols: yellow spheres (Ce1–Ce4) – mixed REE Ca sites; light-blue octahedra – MO6 (M= Al0.55FeCr0.18); blue tetrahedra – SiO4; pink spheres – As atoms; pink pyramids – AsO3; large pink tetrahedral clusters – As4; ochre spheres – S; brown spheres – C; red spheres – O; green spheres – Cl; orange spheres – F.

Figure 9(a) Crystal structure of åsgruvanite-(Ce): detail of the A layer along [001]; (b) detail of the A layer in vicanite-(Ce) along [001] (drawn with data from Ballirano et al., 2002). Symbols as in Fig. 8.

7.1 Crystal structure and chemistry

Åsgruvanite-(Ce) is classified as a nesosilicate and belongs to the Strunz group 9.AH. It exhibits a unique composition and crystal structure. While not precisely a layered topology, the structure of this mineral can be described as being made up of two distinct layers that alternate along the c axis (Figs. 8–10). The first layer (A) is ∼8.4 Å thick and has the following general composition: [(Ce12Ca3)AlSi6(C1.50S0.50)Σ2.00O30(OH)2]15+. The second layer (B) has a thickness of ∼6.7 Å, with the following general composition: [(Ce4Ca2)AsO24Cl4F3]15−. Together, the layers constitute the walls of tunnels running parallel to [100]. The tunnels alternatively host the Cl2 site and a vacant tetrahedron defined by four As3+. Arsenic atoms are located at the apex of two trigonal pyramids pointing towards the centre of the tunnels, sharing their basal edges with Ce2 (As1) and Ce1 and Ce3 (As2). The isolated Si tetrahedron is linked to the MO6 octahedron (M= Al0.55FeCr0.18) through one corner: due to the symmetry of these sites, this results in an octahedron with tetrahedra attached at each of its corners.

Although no known mineral shows a structure directly comparable to that of åsgruvanite-(Ce), some species display noteworthy similarities in terms of either composition or local topology. The most closely related mineral in terms of chemistry is ulfanderssonite-(Ce), with the formula Ce15CaMg2(SiO4)10(SiO3OH)(OH,F)5Cl3. This mineral, like åsgruvanite-(Ce), features structural layers composed of rare earth elements (REEs), calcium, chlorine, and fluorine (Holtstam et al., 2017b); however, it does not contain arsenite or carbonate groups and does not display a crystal structure comparable to åsgruvanite-(Ce).

By comparison, minerals belonging to the vicanite group seem to share more specific structural features with åsgruvanite-(Ce) despite having a fundamentally different overall structure. Vicanite group minerals are characterised by three distinct structural layers containing REEs; Ca; octahedrally coordinated Mg, Fe, or Al; isolated silica tetrahedra; and borate and arsenite groups. Among these, the A layer in particular is structurally comparable to the A layer of åsgruvanite-(Ce) (Fig. 9). Both consist of MO6 octahedra that are located at the origin of the rhombohedral unit cell and that share each corner with silica tetrahedra (e.g. Ballirano et al., 2002; Holtstam et al., 2021b). Furthermore, the REE-hosting sites within the A layer are also similarly arranged in both structures. Nonetheless, some differences can be observed in the neighbourhood of the three-fold axis. In vicanite group minerals, this portion contains, alternatively, three boron planar triangles and a fluorine atom; in åsgruvanite-(Ce), instead, it is occupied by the split site. Another point of comparison lies in the occupancy of the octahedral site. In vicanite group species, M6 can accommodate divalent or trivalent cations, such as Fe2+, Fe3+, Al, and Mg; in åsgruvanite-(Ce), the determination of the dominant cation is more complex due to slight discrepancies between SC-XRD and EMPA results (Table 6). Chemical analyses indicate dominant Al along with subordinate Fe3+ and Cr3+, yielding a total of 17.2 electrons at the M site. However, the refinement of the electron density at this site leads to 21.4 electrons, suggesting dominant Fe (∼66 %) with six equivalent M–O distances (1.995 Å). This discrepancy could point to the possible presence of an undetected minor component: considering the fact that scheelite is part of the mineral association at Åsgruvan, the presence of a small amount of W6+ (0.05 apfu maximum) was hypothesised. The ionic radii of W6+ and Fe3+ are similar (0.60 and 0.64 Å, respectively, for 6-fold coordination; Shannon, 1976). In fact, tungsten could have gone undetected by preliminary energy-dispersive X-ray microanalysis in a scanning-electron microscope (SEM-EDS) investigations due to the likely occurrence in very low amounts (<1 wt %) and, therefore, was not measured in WDS mode. The inclusion of an assumed amount of W6+ equal to 0.05 apfu would increase the calculated number of electrons to 20.9 e−, much closer to the refined value. The presence of significant amounts of tungsten in REE silicates from Bastnäs-type deposits, e.g. in delhuyarite-(Ce) (Holtstam et al., 2017a) and in ulfanderssonite-(Ce) (ca. 3000 ppm; Holtstam et al., 2017b), is well documented.

A particularly unusual feature of åsgruvanite-(Ce) is the split site, which can adopt either a trigonal–planar or trigonal–pyramidal coordination depending on the atom occurring (C or S, respectively) by means of a slight positional shift along [001]. While rare, this kind of substitution has been reported for the thaumasite–hielscherite series of the ettringite group (Pekov et al., 2012). In sulfite-bearing thaumasite, S4+ substitutes for C in a 3-fold coordinated site, causing a similar geometric rearrangement and leading to a split site. The observed C–O (1.342 Å) and S–O (1.497 Å) bond lengths in SO3-rich thaumasite are comparable to those found in åsgruvanite-(Ce) (Table 4).

It is worthwhile to stress that the crystal structure refinement of åsgruvanite-(Ce) indicates a mixed occupancy of REEs and Ca over four independent cation sites, one of which (Ce4) is half-occupied due to stereochemical restraints. Although the mean Ce : Ca ratio derived from both EMPA and SC-XRD data is close to 16:5, this proportion should not be considered to be strictly fixed. In fact, the presence of partially occupied, split anionic sites () suggests local flexibility in both the anionic and cationic sublattices. In particular, the mutually exclusive sites indicate that Cl F− substitution is controlled by local stoichiometric and charge balance constraints. Consequently, the formula Ce16Ca5Al(SiO4)6(AsO3)8(CO3)2Cl3(ClF3)(OH)2 represents an intermediate state between two possible end-member compositions – (Ce18Ca3)Al(SiO4)6(AsO3)8(CO3)2Cl3(□2F6)(OH)2 and (Ce14Ca7)Al(SiO4)6(AsO3)8(CO3)2Cl3(Cl2□6)(OH)2 – defined by full occupancy of either the F1 or Cl1 site, respectively. This flexibility is consistent with the disorder observed in the structure, and it likely reflects variations in local F–Cl activity during crystallisation. Given that the studied sample represents, as for now, the only known occurrence with crystal data, the proposed formula remains that previously stated.

7.2 Paragenesis

As inferred for the Bastnäs-type deposits of Bergslagen in general (Holtstam et al., 2014; Sahlström et al., 2019), the predominant REE minerals at Åsgruvan are metasomatic skarn products, likely formed from hot (>400 °C) magmatic fluids rich in REE ± other metals, Si, Cl, F, etc. that have infiltrated and reacted with carbonate layers. Yet, as is also the case with the arrheniusite-(Ce)-bearing assemblage from the nearby Östanmossa mine (Holtstam et al., 2021b), the åsgruvanite-(Ce) is hosted by a younger generation of calcite, hosted by fractures that cross-cut the main skarn and carbonate assemblages. Thus, these and associated minerals formed at a later stage than the main REE and Fe mineralisation and the associated skarn during brittle tectonic conditions, most likely through fluid-mediated remobilisation of key elements. Such late-stage mineralisation is a relatively common yet previously often overlooked feature in Bastnäs-type deposits (see Andersson et al., 2024).

It is no surprise that åsgruvanite-(Ce) is rare in this environment despite the availability of most of the essential components within the fluid–rock system. The formation depends critically on the presence of As, manifested as very subordinate löllingite in the skarn. In the bona fide first observation of åsgruvanite-(Ce), at the nearby Östanmossa deposit, arrheniusite-(Ce) was the only other As-containing mineral present, with both [AsO3]3− and [AsO4]3− groups detected in the crystal structure (Holtstam et al., 2021b). The combination of As3+ and REE is exceedingly rare in natural minerals; the only known examples are members of the vicanite group (e.g. Ballirano et al., 2002) and cervandonite-(Ce) (Demartin et al., 2008). For the expected redox and pH conditions prevailing in REE mineral-forming fluids (reducing and acidic), As is likely to be available in the form of arsenite (neutral H3AsO3) complexes (Pokrovsky et al., 1996; Nordstrom et al., 2014).

The other essential component with a low overall concentration in the present skarn is chlorine. However, high chlorine concentrations observed in fluid inclusions within bastnäsite from Bastnäs-type localities, corresponding to 6–29 wt % CaCl2 equivalents, provide direct evidence for elevated chloride activity in the fluids (Holtstam et al., 2014), at least for the earliest stage of REE mineralisation. Recent research suggests that Cl− is the most effective ligand for transporting REE3+ in hydrothermal fluids, particularly at higher (>400 °C) temperatures (Migdisov and Williams-Jones, 2014; Migdisov et al., 2016). This likely applies to the formation of Bastnäs-type deposits, although complexation with F− and (SiO4)4− probably also contributed (Holtstam et al., 2014).

It is also worth noting the presence of åsgruvanite-(Ce) as an F-rich REE silicate in the mineral assemblage (the altered zones have the maximum concentration measured), which, together with the REE–fluorocarbonates, indicates elevated fluoride activity during mineralisation. Modern studies have underscored the critical role of high fluorine concentrations in both the transport and, even more importantly, the deposition of REEs in hydrothermal systems (e.g. Migdisov and Williams-Jones, 2014; Migdisov et al., 2016).

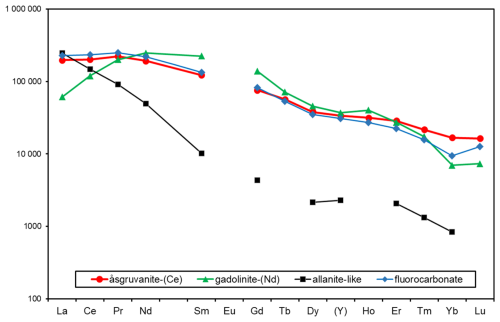

Figure 11Chondrite-normalised REE curves for åsgruvanite-(Ce) and associated minerals based on electron-microprobe analyses.

Chondrite-normalised REE abundances for åsgruvanite-(Ce) and associated REE minerals (Fig. 11) in the Åsgruvan skarn sample are similar to REE mineral assemblages of Bastnäs-type deposits in general (Holtstam and Andersson, 2007; Holtstam et al., 2017b; Škoda et al., 2018; Holtstam et al., 2023). Åsgruvanite-(Ce) is one of the minerals most enriched in Y and the heavy rare earth elements (HREEs). The sample from Östanmossa shows a wider range in terms of REE composition than the present type of material, with, for example, Ce2O3 16.11–20.19, Nd2O3 16.82–18.76, Y2O3 5.81–7.27 (all in wt %), which, in fact, suggests the existence of an Nd-dominant species for some of the spots analysed with EMPA.

To conclude, åsgruvanite-(Ce) is an exceptionally rare mineral, structurally and chemically unique, requiring specific ore-forming conditions to crystallise, such as locally As- and REE-enriched environments. Such conditions evidently developed during a later stage of the REE-mineralising system along the Åsgruvan-Östanmossa skarn horizon.

A CIF is deposited as a Supplement.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/ejm-37-937-2025-supplement.

Preliminary sample examination, preparation, and analyses were done by EJ and SSA. Physical and optical determinations were carried out by EJ, SSA, and DH. SC-XRD data were collected and interpreted by AT and LB. FTIR data were collected by AT and interpreted by AT and DH. Raman data were collected and interpreted by DH. EMPA data were acquired by HJF and OA. AT and DH prepared the paper draft with contributions from all of the co-authors.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a member of the editorial board of European Journal of Mineralogy. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

SC-XRD data were collected at Centro di Cristallografia Strutturale (CRIST), Università degli Studi di Firenze. Daniel Buczko (Uppsala University) is thanked for the assistance during the preliminary electron microprobe analysis. The authors acknowledge two anonymous referees that provided insightful comments and suggestions, greatly improving the paper.

Stefan S. Andersson and Erik Jonsson received funding from the European Union's Horizon Europe research and innovation programme through the project EIS, Exploration Information System (grant no. 101057357).

This paper was edited by Sergey Krivovichev and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Allen, R. L., Lundström, I., Ripa, M., Simeonov, A., and Christofferson, H.: Facies analysis of a 1.9 Ga, continental margin, back-arc, felsic caldera province with diverse Zn-Pb-Ag-(Cu-Au) sulfide and Fe oxide deposits, Bergslagen region, Sweden, Econ. Geol., 91, 979–1008, https://doi.org/10.2113/gsecongeo.91.6.979, 1996.

Andersson, S. S., Jonsson, E., and Sadeghi, M.: A synthesis of the REE-Fe-polymetallic mineral system of the REE-line, Bergslagen, Sweden: New mineralogical and textural-paragenetic constraints, Ore Geol. Rev., 174, 106725, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oregeorev.2024.106275, 2024.

Bahfenne, S., Rintoul, L., Langhof, J., and Frost, R.L.: Single-crystal Raman spectroscopy of natural paulmooreite Pb2As2O5 in comparison with the synthesized analog, Am. Min., 97, 143–149, https://doi.org/10.2138/am.2011.3808, 2012.

Ballirano, P., Callegari, A., Caucia, F., Maras, A., Mazzi, F., and Ungaretti, L.: The crystal structure of vicanite-(Ce), a borosilicate showing an unusual (Si3B3O18)15− polyanion, Am. Min., 87, 1139–1143, https://doi.org/10.2138/am-2002-8-911, 2002.

Bindler, R., Segerström, U., Pettersson-Jensen, I.-M., Berg, A., Hansson, S., Holmström, H., Olsson, K., and Renberg, I.: Early medieval origins of iron mining and settlement in central Sweden: multiproxy analysis of sediment and peat records from the Norberg mining district, J. Archaeol. Sci., 38, 291–300, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2010.09.004, 2011.

Brese, N. E. and O'Keeffe, M.: Bond-valence parameters for solids, Acta Crystallogr., B47, 192–197, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108768190011041, 1991.

Bruker: APEX5 software suite, Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, Wisconsin, USA, 2023.

Demartin, F., Gramaccioli, C. M., and Graeser, S.: The crystal structure of cervandonite-(Ce), an interesting example of As Si diadochy, Can. Mineral., 46, 423–430, https://doi.org/10.3749/canmin.46.2.423, 2008.

Farmer, V. C.: The infrared spectra of minerals, 4, Mineralogical Society monograph, London, United Kingdom, 539, https://doi.org/10.1180/mono-4, 1974.

Flack, H. D., Bernardinelli, G., Clemente, D. A., Lindenc, A., and Spek, A. L.: Centrosymmetric and pseudo-centrosymmetric structures refined as non-centrosymmetric, Acta Crystallogr., B62, 695–701, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108768106021884, 2006.

Frost, R. L. and Kloprogge, J. T.: Raman spectroscopy of some complex arsenate minerals – implications for soil remediation, Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc., 59, 2797–2804, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1386-1425(03)00103-3, 2003.

Geijer, P.: Norbergs berggrund och malmfyndigheter, Sveriges Geologiska Undersökning, Ca, 24, 1–162, 1936 (in Swedish).

Geijer, P.: The geological significance of the cerium mineral occurrences of the Bastnäs type in central Sweden, Arkiv för Mineralogi och Geologi, 3, 99–105, 1961.

Geijer, P. and Magnusson, N. H.: De mellansvenska järnmalmernas geologi. Sveriges Geologiska Undersökning Ca, 35, 1–654, 1944 (in Swedish).

Holtstam, D. and Andersson, U. B.: The REE minerals of the Bastnäs-type deposits, South-Central Sweden, Can. Mineral., 45, 1073–1114, https://doi.org/10.2113/gscanmin.45.5.1073, 2007.

Holtstam, D., Andersson, U. B., Broman C., and Mansfeld, J.: Origin of REE mineralization in the Bastnäs-type Fe-REE-(Cu-Mo-Bi-Au) deposits, Bergslagen, Sweden, Miner. Deposita, 49, 933–966, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00126-014-0553-0, 2014.

Holtstam, D., Bindi, L., Hålenius, U., and Andersson, U.B.: Delhuyarite-(Ce)–Ce4Mg (FeW)□(Si2O7)2O6(OH)2–a new mineral of the chevkinite group, from the Nya Bastnäs Fe–Cu–REE deposit, Sweden, Eur. J. Mineral., 29, 897–905, https://doi.org/10.1127/ejm/2017/0029-2635, 2017a.

Holtstam, D., Bindi, L., Hålenius, U., Kolitsch, U., and Mansfeld, J.: Ulfanderssonite-(Ce), a new Cl-bearing REE silicate mineral species from the Malmkärra mine, Norberg, Sweden, Eur. J. Mineral., 29, 1015–1026, https://doi.org/10.1127/ejm/2017/0029-2670, 2017b.

Holtstam, D., Biagioni, C., and Hålenius, U.: Brattforsite, Mn19(AsO3)12Cl2, a new arsenite mineral related to magnussonite, from Brattforsgruvan, Nordmark, Värmland, Sweden, Min. Petr., 115, 595–609, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00710-021-00749-9, 2021a.

Holtstam, D., Bindi, L., Bonazzi, P., Förster, H.-J., and Andersson, U.B.: Arrheniusite-(Ce), CaMg[(Ce7Y3)Ca5](SiO4)3(Si3B3O18)(AsO4)(BO3)F11, a new member of the vicanite group, from the Östanmossa mine, Norberg, Sweden, Can. Mineral., 59, 177–189, https://doi.org/10.3749/canmin.2000045, 2021b.

Holtstam, D., Casey, P., Bindi, L., Förster, H.-J., Karlsson, A., and Appelt, O.: Fluorbritholite-(Nd), Ca2Nd3(SiO4)3F, a new and key mineral for neodymium sequestration in REE skarns, Mineral. Mag., 87, 731–737, https://doi.org/10.1180/mgm.2023.45, 2023.

Hopsu, V.: Norbergs gruvor på 1960-70- och 80-talen, Sveriges Geologiska Undersökning, Rapporter och Meddelanden, 71, 1–47, 1992 (in Swedish).

Jonsson, E., Nysten, P., Bergman, T., Sadeghi, M., Söderhielm, J., and Claeson, D.: REE mineralisations in Sweden, in: Rare earth elements distribution, mineralisation and exploration potential in Sweden, edited by: Sadeghi, M., Sveriges geologiska undersökning, Rapporter och meddelanden, 146, 20–111, 2019.

Libowitzky, E.: Correlation of O–H stretching frequencies and O–H…O hydrogen bond lengths in minerals, Monatsh. Chem., 130, 1047–1059, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03354882, 1999.

Magnusson, N. H.: Malm i Sverige 1. Mellersta och södra Sverige, Almqvist & Wiksell, Stockholm, 320 pp., ISBN 91-20-05545-5, 1973 (in Swedish).

Mandarino, J. A.: The Gladstone-Dale relationship; Part IV, The compatibility concept and its application, Can. Mineral., 19, 441–450, 1981.

Migdisov, A. A. and Williams-Jones, A. E.: Hydrothermal transport and deposition of the rare earth elements by fluorine-bearing aqueous liquids, Miner. Deposita, 49, 987–997, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00126-014-0554-z, 2014.

Migdisov, A., Williams-Jones, A. E., Brugger, J., and Caporuscio, F. A.: Hydrothermal transport, deposition, and fractionation of the REE: Experimental data and thermodynamic calculations, Chem. Geol., 439, 13–42, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2016.06.005, 2016.

Müller, P., Herbst-Irmer, R., Spek, A. L., Schneider, T. R., and Sawaya, M. R.: Crystal structure refinement, a crystallographer's guide to SHELXL, edited by: Müller, P., OUP Oxford, 213 pp., ISBN 0-19-857076-7, 2006.

Nordstrom, D.K., Majzlan, J., and Königsberger, E.: Thermodynamic properties for arsenic minerals and aqueous species, Rev. Mineral. Geochem., 79, 217–255, https://doi.org/10.2138/rmg.2014.79.4, 2014.

Pekov, I. V., Chukanov, N. V., Britvin, S. N., Kabalov, Y. K., Göttlicher, J., Yapaskurt, V. O., Zadov, A. E., Krivovichev, S. V., Schüller, W., and Ternes, B.: The sulfite anion in ettringite-group minerals: a new mineral species hielscherite, Ca3Si(OH)6(SO4)(SO3)11H2O, and the thaumasite–hielscherite solid-solution series, Mineral. Mag., 76, 1133–1152, https://doi.org/10.1180/minmag.2012.076.5.06, 2012.

Pokrovsky, G., Gout, R., Schott, J., Zotov, A., and Harrichoury, J. C.: Thermodynamic properties and stoichiometry of As(III) hydroxide complexes at hydrothermal conditions, GCA, 60, 737–749, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7037(95)00427-0, 1996.

Sädbom, S.: Gruvhål i Norbergs kommun. Risker för människor och egendom. Bergskraft Bergslagen AB, Rapport för Norbergs kommun, 1–20 + appendices, 2015.

Sahlström, F., Jonsson, E., Högdahl, K., Troll, V. R., Harris, C., Jolis, E. M., and Weis, F.: Interaction between high-temperature magmatic fluids and limestone explains `Bastnäs-type' REE deposits in central Sweden, Sci. Rep., 9, 15203, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-49321-8, 2019.

Sarap, H.: Studien an den Skarnmineralien der Åsgrube im Eisenerzfeld von Norberg, Mittelschweden, GFF, 79, 542–571, https://doi.org/10.1080/11035895709447189, 1957 (in German).

Škoda, R., Plášil, J., Čopjaková, R., Novák, M., Jonsson, E., Galiová, M.V., and Holtstam, D.: Gadolinite-(Nd), a new member of the gadolinite supergroup from Fe–REE deposits of Bastnäs-type, Sweden, Mineral. Mag., 82, S133–S145, https://doi.org/10.1180/minmag.2017.081.047, 2018.

Shannon, R. D.: Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides, Acta Crystallogr., A32, 751–767, 1976.

Sheldrick, G. M.: Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL, Acta Crystallogr., C71, 3–8, 2015.

Spek, A. L.: Structure validation in chemical crystallography, Acta Crystallogr, D Biol. Crystallogr., 65, 148–155, https://doi.org/10.1107/S090744490804362X, 2009.

Taddei, A., Bonazzi, P., Förster, H.-J., Casey, P., Holtstam, D., Karlsson, A., and Bindi, L.: Multi-analytical characterization of an unusual epidote-supergroup mineral from Malmkärra, Sweden: Toward the new (OH)-analog of dollaseite-(Ce), Am. Min., 110, 594–602, https://doi.org/10.2138/am-2024-9438, 2025.

Wilson, A. J. C. (Ed.): International Tables for Crystallography, Volume C: Mathematical, physical and chemical tables, Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht, NL, 1992.