the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Spaltiite, Tl2Cu2As2S5, one more new thallium sulfosalt mineral from Lengenbach quarry, Binn, Switzerland

Stefan Graeser

Dan Topa

Herta Silvia Effenberger

Emil Makovicky

Werner Hermann Paar

George Dincă

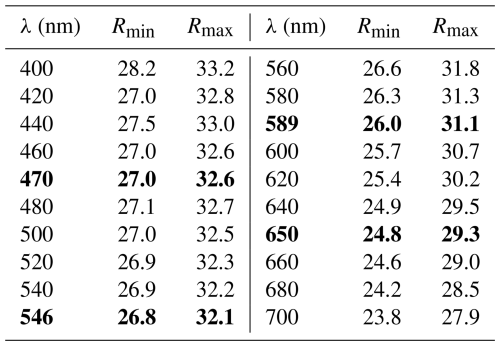

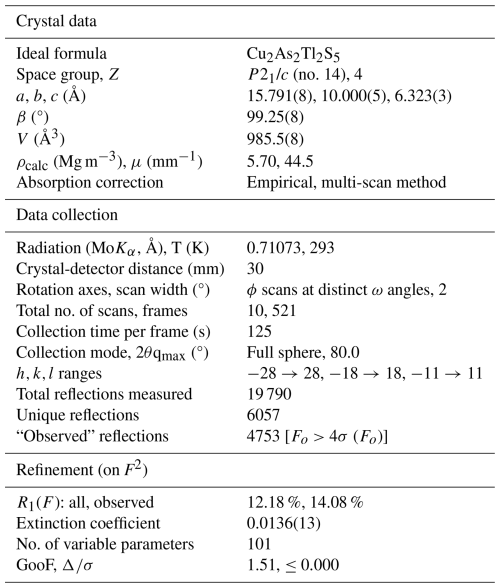

Spaltiite is a new thallium sulfosalt with the ideal formula of Tl2Cu2As2S5. It was found on a dump of the famous mineral locality Lengenbach (Binntal, Canton Valais, Switzerland). A small piece of pure white Triassic dolomite belonging to the Penninic Monte Leone Nappe hosts three euhedral long prismatic to lath-like spaltiite crystals, each approximately 2 mm in length but only ∼0.2 mm thin. The hand specimen contains small quantities of pyrite, drechslerite and hatchite. The spaltiite crystals are greyish to black in colour and extremely soft. The Mohs' hardness is 1.5–2 (VHN15 ranges from 30 to 65, mean 47 kg mm−2). The mono-clinic crystals have a perfect cleavage parallel to {100}, which produces minute and plastic slabs. Reflectance measurements in air yield the following values based on the standard wavelengths (Commission on Ore Mineralogy, COM): 27.0 % 32.6 % (470 nm); 26.8 % 32.1 % (546 nm); 26.0 % 31.1 % (589 nm); and 24.8 % 29.3 % (650 nm). Averaged electron-microprobe analyses (n=10) gave (in wt %) Tl 47.41(19), Cu 15.46(12), Ag 0.15(6), As 17.36(14), Sb 0.41(5) and S 19.20(8), total 99.99(32). The empirical formula is Tl1.94Cu2.04Ag0.01As1.95Sb0.03S5.03, calculated based on 11 apfu. The large crystals exhibit a remarkably homogeneous composition. Spaltiite crystallises in space group P2 (a=15.791(8), b=10.000(5), c=6.323(3) Å, β=99.25(8)°, V=985.5(8) Å3). The crystal structure was determined from single-crystal X-ray diffraction data (R1=12.18 % for 4753 data, with Fo>4σ (Fo) and 101 variable parameters). Spaltiite exhibits a pronounced layered atomic arrangement: two polar Cu–As layers in ( y z) and ( y z), respectively, are related by inversion symmetry. Sandwiched between them are the Tl atoms. These two layers are centred in (0 y z) and ( y z), centrosymmetric but topologically and crystallographically distinct. The eight strongest intensities in the X-ray powder diagram are [d in Å (intensity) hkl]: 3.914 (40) 021; 2.988 (63) 510; 3.496 (45) 311; 2.869 (45) ; 2.652 (36) ; 3.646 (34) ; 2.506 (29) 040; 2.762 (26) 202. The name of the new mineral originates from the nickname “spalti”, which was used during laboratory studies, illustrating the extremely pronounced cleavage (in German, “spalten” means cleave).

- Article

(6448 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(3843 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

One specimen with the only three crystals of the new mineral spaltiite known so far was found on a dump of the famous sulfosalt locality of Lengenbach in the Binn Valley, a narrow valley in Ct. Valais, Switzerland. Samples are hosted in pure white Triassic dolomite of the Penninic Monte Leone Nappe. Curiously, mining and the dumps result only from extensive mineral collections. For more than 200 years, the locality has been well known for a wealth of rare to extremely rare minerals. About 200 minerals have been described from the Binn Valley. So far, it is the type locality of 51 mineral species. In particular, the number of sulfosalts (mainly arsenic Tl and Pb sulfosalts) found there is impressive. Furthermore, the suite is often characterised by chemically unusual and structurally unique minerals. Many of them have only been detected at this locality (cf., Makovicky, 2018; https://www.mindat.org/loc-3207.html, last access: 10 October 2025).

The type specimen that contained the three crystals of spaltiite (Spti) is deposited in the mineral collection of the Natural History Museum in Basel, Switzerland (catalogue no. S210). One of the three crystals served for electron-microprobe analysis (EMPA) and optical and structural investigations. It is deposited in the mineral collection of the Natural History Museum Vienna (no. N 9528). The mineral and its name were approved by the IMA Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification (CNMNC, no. 2014-012; Williams et al., 2014). The name of the new mineral originates from the nickname “spalti” used during the laboratory studies. It characterises the extremely well-developed cleavage (from the German “spalten”, meaning “splitting”).

This study presents a comprehensive characterisation of spaltiite, encompassing the paragenesis, chemical composition, optical behaviour, crystal structure and crystal chemistry (for the latter, see also Makovicky, 2018). The discovery of spaltiite contributes to the understanding of the structural and chemical variation verified in the Tl–As–Cu–S system. It enables a comparative analysis with related species from the same locality and provides further insight into the singularity of the Lengenbach locality, with its unique diversity of the sulfosalt assemblages.

The Lengenbach deposit is located in the Binn Valley, within the administrative division of the Canton of Valais, Switzerland. It is located southeast of the small village of Fäld at an altitude of about 1660 m. The geographical coordinates of Lengenbach are 660.171/135.176 (Swiss grid system CH903/LV03, i.e. 46°21′54′′ N, 8°13′15′′ E). The minerals occur in a bank of snowy-white and sugary dolostone outcropping at numerous sites along the southern valley flank (Graeser, 1965). It is one of the rare cases where a quarry is exclusively mined for sampling mineral specimens to be hosted in collections and not for economic raw material production. The working association Forschungs-Gemeinschaft Lengenbach (FGL) operates the extraction of scientific samples.

The specimen containing the three spaltiite crystals was found by Walter Gabriel in 2009. He is a distinguished mineral collector and an expert for the Lengenbach mine dumps. Gabriel is a member of the FLG, focusing on the search of rare and new minerals in this area. As the sample was found on one of the dumps, the precise location of its origin within the dolomitic host rock remains indeterminable. However, the chemical composition of the new mineral and the associated mineral assemblage suggest that it originally occurred in the so-called “Zone 1” (Graeser et al., 2008), from where most of the thallium-bearing minerals were extracted.

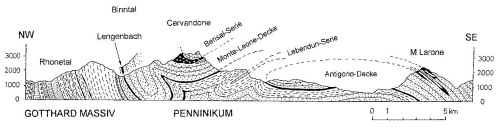

The Triassic dolomite layer at Lengenbach has an estimated thickness of 240 m. It represents the lower part of a metamorphic gneiss nappe (Penninic Monte Leone Nappe). The entire profile is outcropped, ranging from Jurassic to Cretaceous calcshists (“Bündnerschiefer”) and to the pre-Triassic basement gneisses (Fig. 1). The series of rock layers is overturned: the Jurassic dolostone as the youngest series lies at the basis and is overlain by pre-Triassic basement gneisses (Hofmann and Knill, 1996; Roth et al., 2014; Raber and Roth, 2018). The entire series was metamorphosed during the alpine orogeny by upper greenschist to lower amphibolite-facies conditions. The pressures reached up to 4 kb and the temperatures up to 400–500 °C. The mineralised zone occurs in the lower part of the overlying gneiss fold in close proximity to the contact with the younger “Bündnerschiefer” (i.e. in the youngest part of the Triassic sequence). As–Sb and even Bi sulfosalts were identified in additional outcrops of the dolostone banks in the southern part of the valley, but the Lengenbach quarry comprises by far the richest sulfosalt mineralisation in the Binn Valley.

The presence of an astonishingly large number of unique arsenic sulfosalts led to the recognition of the Lengenbach deposit as a highly exceptional location for sulfosalt assemblages. Mineral extraction at the Lengenbach quarry was performed at two distinct sites: the original historical site operated until 1986/1987, and a new site is located 15–20 m higher and to the east of the old quarry. Since 1987, all material has been extracted from the new site only.

Mineralogical and chemical analyses confirmed a large variety of minerals in the deposit, and the extensive diversity of sulfosalts is unique. Predominant are As and, to a minor extent, Sb sulfosalts, with several cations such as Tl, Pb, Ag, Cu, Zn, Cd and Sn. Depending on the cations present, three primary chemical types of mineral were identified:

-

Tl sulfosalts;

-

Pb-dominant sulfides and sulfosalts;

-

Cu–Ag-dominant As sulfides and sulfosalts.

Until 1980, the historical quarry provided primarily Pb sulfosalts (hutchinsonite, hatchite and wallisite but only three Tl sulfosalts). In contrast, in the new quarry, a remarkably high number of Tl-dominated sulfosalts were detected. Among them, spaltiite belongs to the minerals with the highest Tl content. Almost 40 distinct minerals containing Tl as an essential constituent could be identified. For most of them, the Lengenbach deposit is the type locality (Bindi et al., 2015; https://www.mindat.org/loc-3207.html, last access: 10 October 2025). The exceptional unique geochemistry of this mineral deposit is reflected by the fact that out of the 51 type minerals from Lengenbach, 55 % contain Tl, 57 % Pb, 43 % Ag and 96 % As as an essential component in their chemical formulas. The only type mineral that does not belong to sulfosalts is struvite-(K).

As spaltiite was discovered on the dump of the mineral extractions, its original location within the dolomite series could not be specified with certainty. However, the minerals present in the specimen indicate that it originates from the so-called “Zone 1” (Graeser et al., 2008). This is a small stratiform layer in the dolomite series with a high As content (and therefore rich in realgar) in addition to an equally high Tl content.

In Lengenbach, the sulfosalt minerals occur mostly as well-shaped crystals in small druses within the dolomite, rarely exceeding 1 mm in size. They crystallised from hydrothermal solutions mainly enriched with As and Tl. The origin of these two chemical elements has been discussed for more than 90 years. Bader (1934) proposed that these chemical elements were present in the dolomitic sediments prior to the metamorphism and that the sulfosalts were formed by an isochemical reaction. However, Graeser and Roggiani (1976) suggested that the chemical elements As, Cu, Ag, Sn and Tl were remobilised from small sulfide ore concentrations (e.g. as chalcopyrite, tennantite or arsenopyrite) in the pre-Triassic basement gneisses during the alpine metamorphism. The elements then migrated into the neighbouring dolostone and reacted there with minerals of synsedimentary origin (galena, sphalerite, chalcopyrite and pyrite) to form the various sulfosalts. A further theory was developed by Hofmann (1994) and Hofmann and Knill (1996). These authors assumed that the metals present in the basement gneisses had partly migrated into the overlying dolomitic sediments before the folding during the alpine metamorphism. Consequently, the mineral formation might be the result of an isochemical process at high temperatures and pressures.

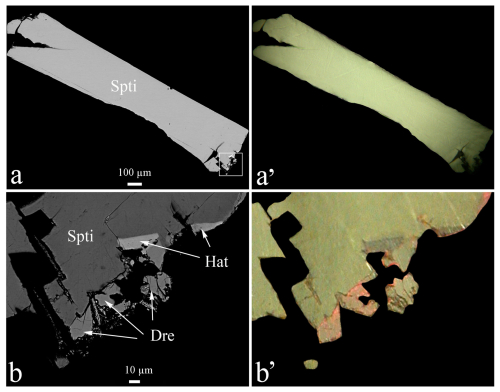

The dolostone where the three spaltiite crystals were detected has the approximate size of mm3. The three samples have almost the same appearance. The crystals are euhedral and long prismatic, are approximately 2 mm in length and only ∼0.2 mm thin. They represent the largest single crystals of a new mineral found in Lengenbach for more than 100 years. The crystals have point symmetry 2/m and are elongated along the c axis with the pinacoid {100} as the most prominent crystal form. Clearly visible are a large number of small {hk0} forms along the c axis as well as a rounded top of the crystal (Fig. 2). Both ore microscopy and chemical analyses demonstrate the high homogeneity of the crystals, a notable distinction to most other Lengenbach sulfosalts. Spaltiite is associated with small quantities of drechslerite (Topa et al., 2019) and hatchite (Fig. 3). The morphology as well as the excellent cleavage parallel to {100} results from the pronounced two-dimensional arrangement of the atoms. All attempts to separate a small fragment for X-ray analyses failed. Only extremely fine lamellae less than 1 µm in diameter were obtained. In addition, trials to pulverise these lamellae for powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) were not successful. Therefore the top of the crystal shown in Fig. 2 was used for PXRD and SCXRD (single-crystal X-ray diffraction) experiments. The microhardness of spaltiite ranges from 1.5 to 2 on the Mohs' hardness scale (i.e. VHN15 ranges from 30 to 65, with a mean of 47 kg mm2). This classifies spaltiite as one of the softest members of the Tl sulfosalts found in Lengenbach; its hardness is almost identical to that of gabrielite (Tl2AgCu2As3S7, VHN10= 18 kg mm−2).

Figure 3(a, a') Backscattered-electron (BSE) image of a spaltiite (Spli) grain and its corresponding plane-polarised optical image showing the homogeneity of the relatively large crystal. (b, b') Enlarged BSE image of a surface of spaltiite (Spti) rim from (a) and its corresponding plane-polarised optical image. Small grains of hatchite (Hat) and drechslerite (Dre) are present.

In the hand specimen, the crystals exhibit a metallic lustre and a lead-grey colour. Spaltiite is indistinguishable from many other Lengenbach sulfosalts with the naked eye. In the ore microscope, a polished section of spaltiite appears as white under plane-polarised incident light with common red internal reflections. Neither pleochroism nor bireflectance is discernible. Anisotropy is weak in air, with a reddish-brown to greenish tint. It is more distinct in oil, with a violet to greenish rotation tint. The reflectance values in air are moderate (Table 1), yet they belong to the highest values measured for Tl sulfosalts from Lengenbach. Quantitative data on reflectance were obtained by means of a WTiC standard and a Leitz MPV-SP microscope photometer.

Initial qualitative chemical analyses were made with a JEOL “Superprobe” JXA 8600F electron microprobe, employing an EDS system, on an unpolished surface of the grain, shown in Fig. 2. The presence of Cu, As, Tl and S was documented, indicating a distinctive chemistry.

The same polished section that was subjected to the optical study (whole crystal of 2 mm, parallel to the a axis) was used for the electron-microprobe studies. Once more, the crystal appeared chemically homogeneous with one exception at its basis, where the crystal was intergrown with other sulfosalts (Fig. 3).

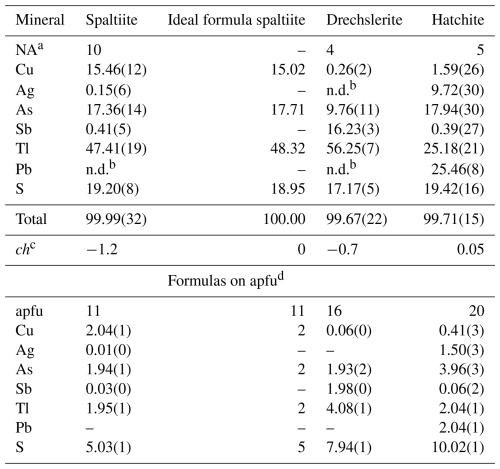

Subsequent chemical analyses of spaltiite (10 points on the main grain) and associated minerals were carried out using a JEOL “Hyperprobe” JXA 8530F field-emission gun electron microprobe (FE-EPMA) in the Central Research Laboratories of the Natural History Museum, Vienna, employing JEOL analysis software (WDS mode, 25 kV, 20 nA, 2 µm beam diameter, count time 10 s on peak and 5 s on background positions). The following emission lines and standards were used: AsLα, TlLα and SKα (lorándite, TlAsS2), PbMα (galena), AgLα (Ag metal), CuKα (chalcopyrite) and SbLα (stibnite). Analytical data are given in Table 2. For spaltiite, Ag and Sb seem to be trace elements, while Pb is entirely absent. The empirical formula is Cu2.04Ag0.01Tl1.94As1.95Sb0.03S5.03, calculated on the basis of 11 atoms. The ideal formula is Cu2Tl2As2S5, which requires (in wt %) 15.02 Cu, 48.32 Tl, 17.71 As and 18.95 S, total 100 %. Among the Tl minerals from Lengenbach, spaltiite is one of the richest in Tl content.

Table 2Average chemical composition data (in wt %) for spaltiite, drechslerite and hatchite.

a Number of analyses. b Not determined or under detection limit (0.05 wt % for Ag and 0.1 wt % for Pb). c ch charge balance calculated with atomic per cent values as (Σ cation val.-Σ anion val.). d Atoms per formula unit for Z=4 for spaltiite and Z=1 for drechslerite and hatchite.

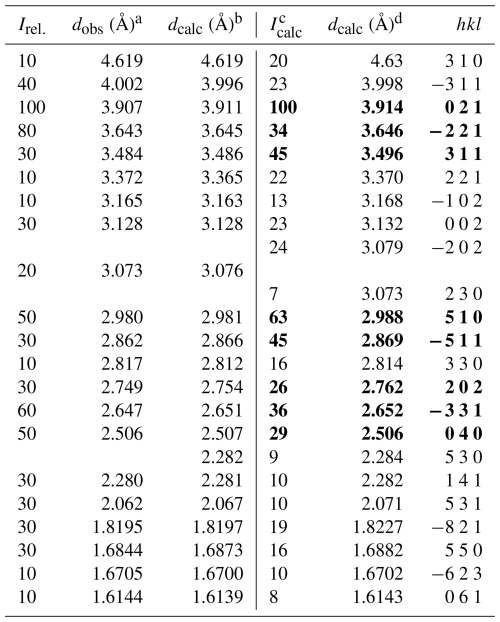

6.1 PXRD

Initial studies of the title mineral were conducted using PXRD. Since the pulverising of the mineral was not feasible for use with a conventional Debye-Scherrer camera, a Gandolfi camera was utilised for the analysis of the entire single crystal where only the tip was irradiated with X-rays. The result was a diagram of a surprisingly high quality, and numerous sharp lines could be identified. The reason for the unexpectedly good quality of the Gandolfi diagram is the single crystal's very uncommon homogeneity despite the large size (2.1 mm in length, Fig. 2) and a reasonably small collimator. The diagram clearly differs from any other known minerals. Preliminary single-crystal studies using Weissenberg- and Precession cameras, once more conducted on the tip of the entire crystal, gave a mono-clinic unit cell. The systematic extinctions clearly and unambiguously revealed the space group P2. Based on the crystal-lattice dimensions, a complete indexing of the diagram taken with the Gandolfi camera was possible (Table 3).

Table 3X-ray powder diffraction data for spaltiite (Gandolfi system) and the calculated one. The most intense lines are marked in bold.

a d values obtained from Gandolfi camera (114.6 mm ∅) using FeKα radiation. b d values calculated for a cell with a=15.821(9), b=10.023(6), c=6.334(4) Å; β=99.21(6)°. c,d Theoretical powder pattern calculated with PowderCell 2.3 (Kraus and Nolze, 1996) based on the data from the crystal structure determination.

6.2 Single-crystal X-ray diffraction

Because of the extreme scarcity and pronounced divisibility of the title mineral, it was impossible to separate a fragment suitable for X-ray studies. Therefore, a much too large crystal served for the SCXRD investigations. This is particularly unfortunate because of the high absorption coefficient of thallium atoms. The sample was stuck on a glass fibre and mounted on a four-circle Nonius Kappa diffractometer (CCD detector, 300 µm capillary optics collimator, conventional X-ray tube, monochromated MoKα radiation). The unit-cell parameters were obtained by least-squares refinements from the 2θ values of the positions of all measured Bragg reflections. Corrections for Lorentz polarisation, absorption (multi-scan method) and extinction effects were applied, and complex neutral atomic scattering functions from Wilson (1992) were used. For data collection, structure solution and refinements served the programs COLLECT, JANA and SHELXL-97 (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997; Petříček et al., 2023; Sheldrick, 2015). In accordance with the systematic extinctions that are characteristically unambiguous for space group P2 (0k0 observed with k=2n and h0l with l=2n only) the reflection statistics is also consistent with centrosymmetry.

The atomic coordinates of the Tl, Cu and As atoms were found by charge flipping and that of the S atoms by succeeding difference Fourier summations. In the final stage of refinement, all atom positions were treated as fully occupied, and anisotropic displacement factors were allowed to vary. Due to the unlucky large crystal used for data collection, this is considered to be strongly influenced by relicts of the insufficiently corrected absorption phenomena.

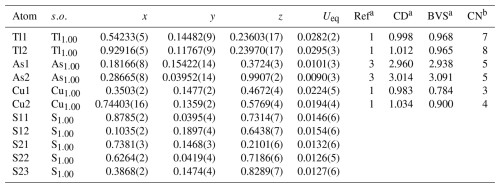

Table 4 provides details of the data collection and results of the structure refinement of spaltiite. Full details are given in the CIF file in the Supplement (S1_spaltiite.CIF file). Table 5 compiles the fractional atomic coordinates and the equivalent isotropic displacement parameters. Tables 6 and 7 compile the cation–anion and the cation–cation bond lengths, respectively. Further details of the crystal structure investigations may be obtained from the joint CCDC/FIZ Karlsruhe online deposition service at https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/? (last access: 20 December 2025) by quoting the deposition number CSD-2505991.

Table 5Sites, site occupancies (, fractional atom coordinates, equivalent isotropic displacement parameters (in Å2), charge distribution and bond-valence sum values of spaltiite.

a Ref is the charge of the site obtained from refinement, whereas CD and BVS represent the charge distribution and bond-valence sum values, respectively, calculated for the cation sites with the program ECoN21 (Ilinca, 2022). b Coordination number.

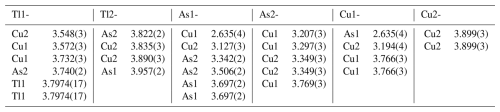

Table 7Selected interatomic cation–cation distances (Å) in spaltiite (up to 4.0 Å for the Tl atoms and up to 3.8 Å for the As and Cu atoms).

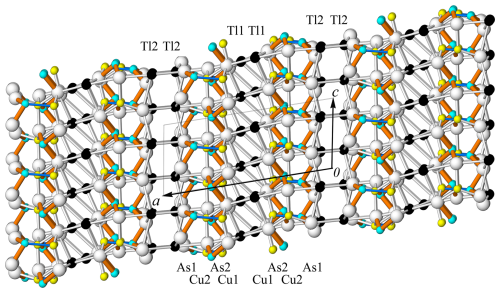

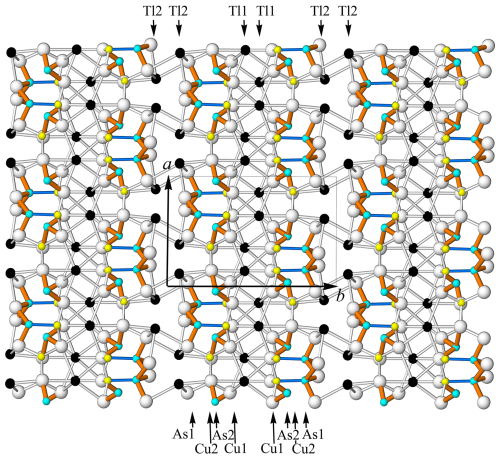

Figure 4The crystal structure of spaltiite viewed along the c axis. The one-dimensional arrangements of the Tl, As and Cu atoms along [100] are indicated. Atom and bond coding: black: Tl, light blue: As, yellow: Cu, white: S, brown: short As–S bonds, blue: short Cu1–As1 bonds.

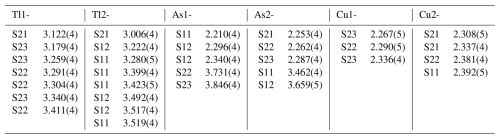

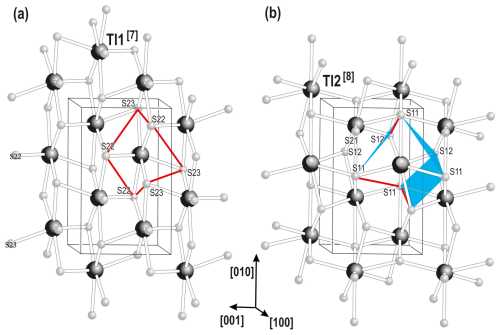

Makovicky (2018) compiled many features of the crystal structure and the crystal chemistry of spaltiite. Apart from a short overview, some further details are given below. The asymmetric unit of the crystal structure of spaltiite each contains two Tl1+, Cu1+ and As3+ cations besides five anion positions. The crystal structure of spaltiite viewed along [001] and [010] is presented in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively. Considering Tl–S bond lengths shorter than the Tl–Cu and Tl–As contacts (i.e. Tl–S is between 3.007 and 3.521 Å), the Tl1 and Tl2 atoms are [7] respectively [8] coordinated. Due to the space requirement of the steric active lone-electron pair of the Tl1+ ions, these two coordination polyhedra exhibit significant angular distortions. However, in both cases five S atoms are in an approximate planar arrangement with the Tl1 and Tl2 atoms, deviating by only 0.0416(13) and 0.0569(15) Å from these planes. The Tl1[7]S7 polyhedron forms a distorted pentagonal bipyramid. Within the equatorial 5-membered ring, S–Tl1–S varies between 66.4 and 78.2° (ideal value 72°), but the axis of the polyhedron is strongly bent (151.1°). The coordination figure Tl2[8]S8 is also related to a pentagonal bipyramid with a 5-membered equatorial ring (S–Tl2–S between 62.9 and 84.9°), but the top and base are represented by one and two S atoms, respectively. Alternatively, the Tl2[8]S8 polyhedron can be approximated by a distorted tetragonal antiprism.

The Cu1 atom is slightly pyramidal [3] coordinated (the sum of the three S–Cu1–S angles amounts to 346.4°). The Cu1 atom is shifted out of the basal plane towards an As1 atom, indicating some interaction (Cu1–As1 distance 2.635 Å). This distance is longer than the sum of the radii of the Cu and As atoms, unaffected whether ion or metal radii are considered. This unusual bond length was extensively discussed by Makovicky (2018) as it is longer than expected for a tetrahedral Cu[4] coordination, and thus it is at the upper limit commonly observed in Cu arsenides. Compared to a regular tetrahedron, the bond angles at the Cu2[3S+As] atoms split into increased S–Cu1–S (average 115.5°) and decreased S–Cu1–As1 (102.5°) values. Makovicky (2018) mentions the possibility of an interaction between the Cu1 atom and the lone-electron pairs of the As1 atom. One of the two Cu1–S23 bond lengths is significantly increased, with the other one decreased. The S23 atom links the Cu1[3Cu+1As] atoms to a chain parallel to [001]. Consequently, the distinct bond lengths Cu1–S23 cannot result from bond-valence requirements but seem to be triggered by the interconnection of the coordination polyhedra among each other and by the space requirements of the lone-electron pair.

The four S atoms coordinating the Cu2 atom form a slightly distorted tetrahedron. The Cu2–S bond lengths split into two shorter ones (both to S21 atoms) and into two somewhat longer ones (S11 and S22 atoms). The increased Cu2–S11 bond lengths are consistent with the coordination: only the S11 atom in spaltiite is coordinated by one Cu and one As atom (besides Tli+ ions). The different Cu2–S21 and Cu2–S22 bond lengths are not triggered by the different coordination of the S atoms: besides the weak interaction with the highly coordinated Tl1+ ions, both these S atoms are coordinated by two Cu atoms and by one As atom. It should be mentioned that the average S–Cu2–S bond angle of 109.3° matches the ideal value closely. Both the As1 and As2 atoms are in a pyramidal [3] coordination by S atoms. Due to the additional As1–Cu1 interaction, the average S–As1–S bond angle (97.9°) is smaller compared to S–As2–S (100.7°). The As1S3 pyramid is steeper than the As2S3 pyramid (the As atoms are off their basal planes by 1.119(3) and 1.038(3) Å).

Spaltiite is characterised by densely packed Cu2As2S5 layers parallel to {100}. Sandwiched between them are the thallium atoms. Each of the Cu1S3, Cu2S4 and As1S3 coordination figures are corner linked to chains parallel to [001]; the As2S3 pyramids are not connected to each other. The top of the AsS3 pyramids point to the centre of the layers. Thus, channels are formed that host the lone-electron pairs of the Tl atoms.

The coordination figures around the Cu and As atoms are again corner linked but to a two-dimensional arrangement. Thereby, the Cu1S3 and the AsS3 units form CuAs2S5 slabs parallel to [001], which are linked by the Cu2S4 tetrahedra. The slabs are centred by the lone-electron pairs of the As atoms and the Cu1–As1 interaction. The Cu1S3 triangle, one S22–S23 edge of the As2S3 unit and the base of the As1S3 pyramid mark the top as well as the bottom face of the Cu2As2S5 layers. The Cu2S4 tetrahedra cause a one-dimensional necking of the layer, which enables the Tl1+ ions to link via four respectively five S atoms to the layers. The two Cu2As2S5 layers in ( y z) and ( y z) are related by inversion symmetry. They are pronounced polar and have layer symmetry pc. Within the Cu2As2S5 layer, the S atoms themselves exhibit three distinct two-dimensional arrangements. The S11 and S12, respectively S22 and S23 atoms, border the Cu2As2S5 layers, and the S21 atoms are centred between them.

The Tl1S7 and Tl2S8 coordination polyhedra occur in two topologically distinct layers centred in ( y z) and (0 y z), respectively. Some relations are evident (Fig. 6).

Figure 6The linkage of the Tl-sulfide layers in spaltiite. Common edges that face between the coordination figures are indicated by red lines and blue faces. Tl–S bonds up to 3.6 Å are considered.

Both exhibit layer–group symmetry p2; they are formed by four- and six-membered Tl2S2 and Tl3S3 rings, and the Tl atoms each have six Tl atom neighbours. However, the Tl1S7 polyhedron is linked via six edges but the Tl2S8 polyhedron via three edges and three faces with the neighbouring Tl atoms. Only the S21 atom is not involved in these rings but interlink both the Tl layers. The shortest Tl bonds in spaltiite are Tl1–S21 and Tl2–S21. These bonds are approximately parallel to [001], and the Tl1–S21–Tl2 bond angle is 171.03(11)°. Most noticeable is the different width of the layers: the Tl atoms are each arranged in two planes; the two Tl1[7] atom planes are separated by 1.337 Å and the Tl2[8] atom planes by 2.237 Å.

The new mineral species spaltiite is a very rare Tl sulfosalt. It was found in the Lengenbach quarry, supporting once again the complexity of this unique deposit. Among the numerous Tl sulfosalt minerals from Lengenbach, spaltiite is remarkable for more than one reason. (i) It is by far the largest idiomorphic sulfosalt that has been found in the last 100 years. (ii) It shows only a minor intergrowth with other sulfosalts. This is extremely rare for sulfosalts found in Lengenbach; typically, they are closely intergrown with numerous other sulfosalt minerals. (iii) Spaltiite shows no evidence of any solid solution. (iv) Spaltiite is extremely rare. So far, only one hand specimen with three crystals has been found. (v) The pronounced cleavage prevent a careful sample preparation of a crystal chip suitable for PXRD and SCXRD analysis. The atomic arrangement of spaltiite reflects its morphology with a platelet shape parallel to [100] and an elongation in [001].

The characterisation of spaltiite enriches the knowledge of the crystal chemistry within the Tl–As–Cu–S system and extends the already long list of Tl sulfosalts found in Lengenbach. The simultaneous occurrence of the chemical elements Tl–As–Cu–S is rare for minerals – only 11 species are known so far. Spaltiite is the sixth mineral out of this group found in Lengenbach: for gabrielite (Tl6Ag3Cu6(As,Sb)9S21), wallisite (TlPb(Cu,Ag)As2S5), stalderite (Tl6(Cu,Ag)(Fe,Zn,Fe,Hg)2(As,Sb)2S6) and ferrostalderite (TlCuFe2As2S6), it is the type locality; only routhierite (Tl(Cu,Ag)(Hg,Zn)2(As,Sb)2S6) was detected earlier in the French Alps. The occurrence in a zone known for high thallium and arsenic concentrations provides further evidence of the role of hydrothermal fluids in mobilising and concentrating these elements during the alpine metamorphism.

Crystallographic data for the refinement of spaltiite are available in the Supplement as S1 and S2.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/ejm-38-27-2026-supplement.

SG initiated the project and obtained the experimental XRPD. DT performed EMPA and part of the SCXRD experiments. HSE performed the last SCXRD experiment. EM described the crystal structure. WHP worked on optical properties. All authors interpreted the obtained data. The paper was written by SG, DT and HSE, with contributions from GD.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors express their gratitude to Goran Batic for help with the sample preparation. We thank the editor Marco Ernesto Ciriotti for handling the paper and the two anonymous reviewers for their critical remarks that have improved the article.

This paper was edited by Sergey Krivovichev and reviewed by Marco Ernesto Ciriotti and one anonymous referee.

Bader, H.: Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Gesteine und Minerallagerstätten des Binnentals, Schweizer mineralog. Petrogr. Mitt., 14, 319–441, 1934.

Bindi, L., Biagioni, C., Raber, T., Roth, P., and Nestola, F.: Ralphcannonite, AgZn2TlAs2S6, a new mineral of the routhierite isotypic series from Lengenbach, Binn Valley, Switzerland, Mineralogical Magazine, 79, 1089–1098, https://doi.org/10.1180/minmag.2015.079.5.05, 2015.

Graeser, S.: Die Mineralfundstellen im Dolomit des Binnatales. Schweizerische Mineralog. Petrogr. Mitt., 45, 597–795, https://doi.org/10.5169/seals-35205, 1965.

Graeser, S. and Roggiani, A. G.: Occurence and genesis of rare arsenate and phosphate minerals around PizzoCervandone,Italy/Switzerland, Soc.It.Min.Petr.Rendiconti XXXII, 279–8, 1976.

Graeser, S., Cannon, R., Drechsler, E., Raber, T., and Roth, P.: “Faszination Lengenbach” – Abbau Forschung Mineralien, 1958–2008, CristalloGrafik Verlag Lothar Meckel Achberg/D, 192 pp., ISBN 978-3-940814-16-6, 2008.

Hofmann, B. A.: Formation of a sulfide melt during Alpine metamorphism of the Lengenbach polymetallic sulfide mineralization, Binntal, Switzerland, Mineralium Deposita, 29, 439–442, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01886964, 1994.

Hofmann, B. A. and Knill, M. D.: Geochemistry and genesis of the Lengenbach Pb-Zn-As-Tl-Ba-mineralisation, Binn Valley, Switzerland, Mineralium Deposita, 3, 319–339, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02280795, 1996.

Kraus, W. and Nolze, G.: POWDER CELL – A Program for the Representation and Manipulation of Crystal Structure and Calculation of the Resulting X-Ray Powder Pattern, Journal of Applied Crystallography, 29, 301–303, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0021889895014920, 1996.

Makovicky, E.: Modular Crystal Chemistry of Thallium Sulfosalts, Minerals, 8, 478, https://doi.org/10.3390/min8110478, 2018.

Niggli, E.: Die geologische Stellung der Mineralfundstelle Lengenbach, in: Die Mineralfundstelle Lengenbach im Binnatal, Separatdruck aus Jahrbuch des Naturhistorischen Museums der Stadt Bern 1966–1968, 21–25, 1968.

Otwinowski, Z. and Minor, W.: Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode, Methods Enzymology, 276, 307–326, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X, 1997.

Petříček, V., Palatinus, L., Plášil, J., Dušek, M.: Jana2020 – a new version of the crystallographic computing system Jana, Zeitschr. Kristallogr., 238, 271–282, https://doi.org/10.1515/zkri-2023-0005, 2023.

Raber, T. and Roth, P.: The Lengenbach Quarry in Switzerland: Classic Locality for Rare Thallium Sulfosalts, Minerals, 8, 409, https://doi.org/10.3390/min8090409, 2018.

Roth, P., Raber, T., Drechsler, E., and Cannon, R.: The Lengenbach Quarry, Binn Valley, Switzerland, Mineralogical Record, 45, 157–196, 2014.

Sheldrick, G. M.: Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL, Acta Crystallographica, C71, 3–8, https://doi.org/10.1107/S2053229614024218, 2015.

Topa, D., Graeser, S., Stoeger, B., Raber, T., and Stanley, C.: Drechslerite, IMA 2019-061, CNMNC Newsletter No. 52, Mineralogical Magazine, 83, https://doi.org/10.1180/mgm.2019.73, 2019.

Williams, P. A., Hatert, F., Pasero, M., and Mills, S. J.: IMA Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification (CNMNC) – Newsletter 20, new minerals and nomenclature modifications approved in 2014, Mineral. Mag., 78, 549–558, https://doi.org/10.1180/minmag.2014.078.3.05, 2014.

Wilson, A. J. C. (Ed.): International Tables for Crystallography, C. Kluver, Dordrecht, the Netherlands, ISBN 0-7923-6590-9, 1992.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Occurrence

- Minerals from Lengenbach and their formation

- Physical and optical properties

- Chemical composition

- X-ray crystallography

- Discussion

- Conclusions

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Review statement

- References

- Supplement

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Occurrence

- Minerals from Lengenbach and their formation

- Physical and optical properties

- Chemical composition

- X-ray crystallography

- Discussion

- Conclusions

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Review statement

- References

- Supplement