the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The crystal structure of launayite from Taylor Pit, Madoc, Ontario, Canada: crystal chemistry, modulated superstructures, and parent modular structure compared with rouxelite

Dan Topa

Berthold Stoeger

Frank Norman Keutsch

Gheorghe Ilinca

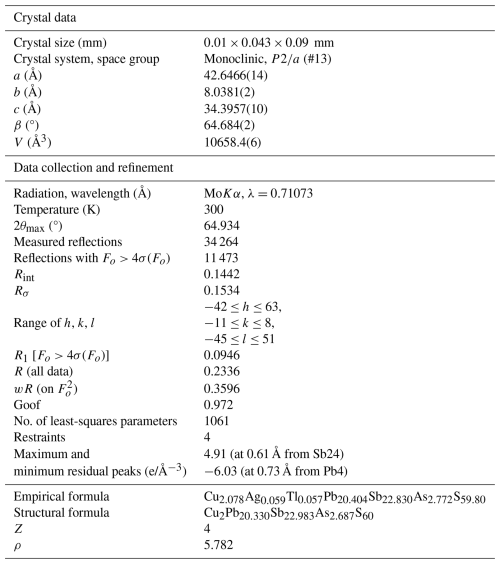

The crystal structure of launayite, ideally Cu2Pb20(Sb,As)26S60 (Z=4) from Taylor Pit, Madoc, Ontario, Canada, has been solved for the first time using the single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) method. The mineral is composed of distinct superstructures that can be derived from the same parent structure. The structure of the main component is monoclinic and has been solved in the space group , with cell parameters a=42.6466(14), b=8.0381(2), c=34.3957(10) Å, β=64.684(2) °, and V=10 658.4(6) Å3 from an untwined crystal. The asymmetric unit of launayite contains 48 cation sites and 60 sulfur sites. Final refinement resulted in an R1 value of 0.0955 for 11 741 unique reflections. The structural formula obtained from SCXRD study is Cu2Pb20.330Sb23.024As2.689S60, Z=4, in agreement with the formula Cu2.078Ag0.059Tl0.057Pb20.404Sb22.830As2.772S59.80 from microprobe analysis. The structure of launayite can be viewed both as a boxwork structure and as a rod-based structure. The modular description of the launayite structure reveals a very close relationship with the structure of rouxelite: the parent structures of both can be regarded as merotypes. A full comparison of the crystal chemistry and modular description of both structures is presented.

- Article

(23911 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1288 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Launayite is a unique (Cu)-Pb-Sb(As) sulfosalt mineral, first described by Jambor (1967a, b) from Taylor Pit, Madoc, Ontario, Canada. Other very rare minerals from the same locality, identified and described simultaneously with launayite by Jambor, are playfairite, sorbyite, madocite, sterryite, twinnite, guettardite, dadsonite, and veenite. The crystal structure of dadsonite (Makovicky et al., 2006), sterryite (Moëlo et al., 2012), twinnite (Makovicky and Topa, 2012), guettardite (Makovicky et al., 2012), and veenite (Topa and Makovicky, 2017) were resolved in the meantime. The veenite crystal structure was obtained from Madoc material, and the rest of the crystal structures employed materials from other deposits. The crystal structure of launayite, playfairite, madocite, and sorbyite remained unknown up to now.

The first chemical formula published by Jambor for launayite was Pb22Sb26S61. X-ray powder diffraction indicated that the crystal is monoclinic, with unit cell parameters a=42.6(7), b=8.04(5), c=32.3(6) Å, β=102.02(25) °, and V=5370.8 Å3. He noted that the b parameter was twice the length of a pseudocell axis ( Å), based on the observation that diffraction rows corresponding to 2b′ were “extremely weak and barely discernible”. For the pseudocell, diffraction spots occurred only when h+k were even, leading him to suggest the space group C2, Cm, or (Jambor, 1967b).

In 1982, Jambor and co-authors reported new electron microprobe analyses of launayite from the same type material (Jambor et al., 1982), which revealed minor amounts of Cu, ranging from 1.3 wt % to 1.4 wt %. The authors stated that “its non-essential character is evident in that launayite has been synthesised in the pure PbS–Sb2S3 system” (Nekrasov and Bortnikov, 1977) and therefore concluded that the small amount of Cu was not significant and did not need to be considered in the ideal chemical formula.

The re-examination of the chemistry of tintinaite–kobellite series by microprobe analyses conducted and published by Moëlo et al. (1984) pointed to the conclusion that “minor amounts of Cu incorporated in a specific tetrahedral site is thought to stabilise some Pb sulfosalts at low temperatures”. Some examples were given, including launayite, with a new formula Pb10(Sb,As)13CuS30, based on results from Moëlo (1983).

The review of sulfosalt systematics published as a report of the sulfosalt sub-committee of the IMA Commission on Ore Mineralogy by Moëlo et al. (2008) placed launayite with formula CuPb10(Sb,As)13S30 and unknown crystal structure into an unclassified group of sulfosalt minerals.

In connection with our previous and ongoing analytical work on Madoc sulfosalt material, we performed additional microprobe analysis and a single-crystal study of this mineral. This study presents the crystallography and crystal chemistry of launayite from Madoc, Ontario, Canada. The present paper expands the knowledge and understanding of this very rare and complex mineral and its close structural relationship with rouxelite, while also contributing to the broader field of sulfosalt research.

Launayite is extremely rare, apparently unique up to now, and difficult to obtain due to the exhaustion of the Taylor Pit deposit. Upon request we were kindly provided with type material of launayite (sample MC 61062) by Inna Lykova, Laura Smyk, and Michael Bainbridge from the Canadian Museum of Nature for re-analysing and attempting to solve the crystal structure of launayite.

Figure 1Photograph of the polished type specimen of launayite with catalogue number MC 61062, from Taylor Pit, Madoc, Ontario, Canada, showing two black sulfosalt aggregates (ca. 2×3 mm in embedding material) containing launayite.

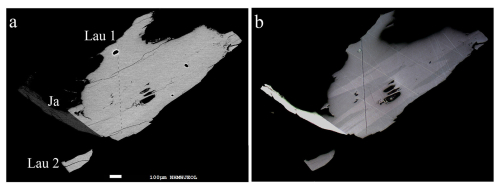

Figure 1 depicts the re-polished type specimen of launayite (MC 61062) which contains two black sulfosalt aggregates in embedding material. The backscattered electron image of aggregate no. 2 from Fig. 1 is presented in Fig. 2a. It shows one large launayite (Lau) grain (1) in contact with jamesonite (Ja) and a second small launayite (Lau) grain (2), which was mechanically extracted after EMPA analyses and after permission for crystal extraction was obtained. Additional launayite material, beside aggregate no. 1 from Fig. 1, was found in only two other samples, MC 12177 (grain #6) and MC 12178 (grain #2), in our larger ongoing study on Madoc.

Figure 2(a) Backscattered electron image of aggregate no. 2 from Fig. 1 showing one large launayite grain (Lau1) in contact with jamesonite (Ja) and a small launayite grain (Lau2), which was mechanically extracted after EMPA analyses. (b) Corresponding plane-polarised optical image, which reveals twin lamellae of launayite in the large grain but not in the small one.

Chemical analyses of launayite and associated minerals were carried out using a JEOL “Hyperprobe” JXA 8530F field emission gun electron microprobe (FE-EPMA) at the Central Research Laboratories of the Natural History Museum, Vienna. The analyses employed JEOL and Probe for EPMA software (WDS mode, 25 kV, 20 nA, 1.5 µm beam diameter, count time 15 s on peak and 5 s on background positions). The following emission lines and standards were used: AsLα and TlLα (lorándite, TlAsS2), PbMα (galena), AgLα (Ag metal), SbLα and SKα (stibnite), HgLα (cinnabar), and CuKα (chalcopyrite). Other elements such as Bi, Fe, and Cl were sought but not detected. Proper empirical correction was made for the interference of the third order of the SbLα line with the analytical AsLα line. Under the described analytical conditions, the detection limits for the measured elements in the launayite matrix were as follows (expressed in wt %): Cl 0.03; S, Cu, and Fe ∼0.04; As, Ag, and Sb ∼0.06; Tl 0.08; and Hg, Tl, Pb, and Bi ∼ 0.1.

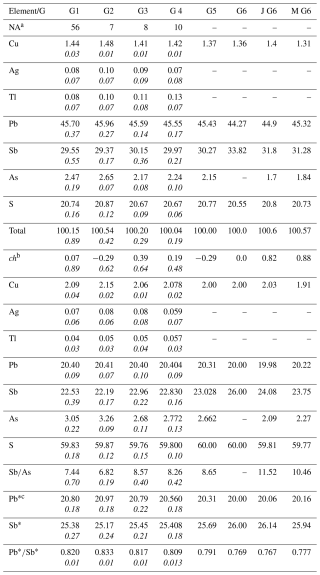

Table 1Average chemical composition data (in wt %) of launayite (Lau) from Madoc, grouped as follows: G1, all measured points; G2: high (Cu, As) compositions; G3: low (Cu, As) compositions; G4, composition of the extracted grain for SCXRD study. G5 and G6 represent chemical composition derived from structural (SREFF) and ideal formulae. J and M represent analyses on launayite from Madoc by Jambor and Moëlo. Empirical formulae are calculated based on 108 apfu (ΣMe + ΣS for the asymmetric unit and Z=4). Values in italics represent standard deviations.

a Number of point analyses. b ch: charge balance values calculated as (Σcation valence − Σanion valence) using atom per cent values. c Pb∗ = Pb + 2(Ag + Tl + Cuextra), Sb∗ = Sb + As − (Ag + Tl + Cuextra) and Cuextra = Cu − 2, calculated using apfu.

Based on all 54 analytical measured points of launayite, we defined four main groups of analyses, represented by their mean values and presented in Table 1: (1) all 54-point analyses combined, (2) a group with low Cu and As contents, (3) a group with high Cu and As contents, and (4) a group for the grain used in the single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) study. All four groups show good charge balance and are characterised by low standard deviations for the measured elements. The detected amounts of Ag and Tl are very low but clearly over the detection limits. The high Cu and As values and the low Cu and As values are not correlated. Variations of As are correlated with variations of Sb and indicate an substitution.

The empirical formulas for all groups were calculated based on 108 apfu, Z=4 (from the SCXRD study). The empirical formula for the grain used in the SCXRD study is Cu2.078Ag0.059Tl0.057Pb20.404Sb22.830As2.772S59.80.

A plane-polarised optical image (Fig. 2b) of aggregate no. 2 reveals twin lamellae of launayite in the large (Lau1) grain but none for the small (Lau2) launayite grain. The latter grain was extracted mechanically from the polished sample and used for the SCXRD study.

Intensity data of a small needle-shaped fragment were collected at room temperature using a STOE StadiVari diffractometer system equipped with an EIGER2 1M CdTe detector. Finely collimated MoKα radiation was employed, utilising finely sliced ω scans and a detector distance of 70 mm. Data were processed using STOE X-Area software, and intensities were scaled with STOE LANA (Koziskova et al., 2016).

The structure of launayite was solved by the dual-space method implemented in SHELXT (Sheldrick, 2015a), which revealed most of the atom positions, and was subsequently refined using SHELXL (Sheldrick, 2015b). In subsequent cycles of the refinement, remaining atom positions were deduced from difference Fourier syntheses by selecting from among the strongest maxima at appropriate distances.

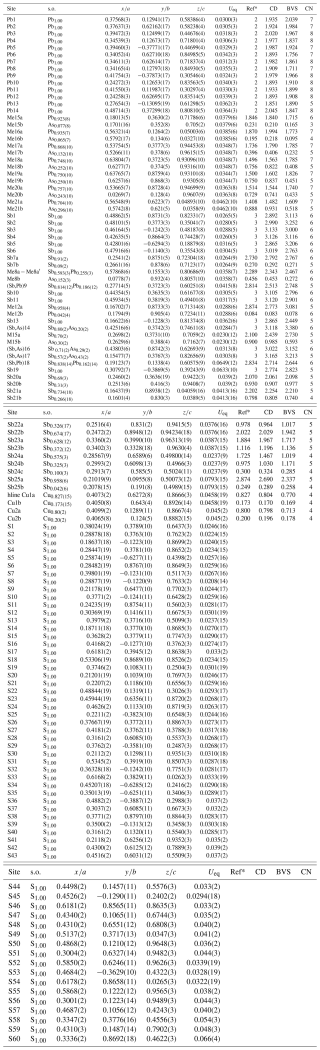

Details on data collection and results of the structure refinement of launayite are given in Table 2, and full details are given in the CIF file deposited as a Supplement (S1_launayite.CIF file). The fractional atomic coordinate, occupancies, anisotropic atomic displacement parameters, charge distribution (CD) values, bond valence sum (BVS), and coordination values for all sites are compiled in Table 3. Table 4 gives selected Me–S bond lengths.

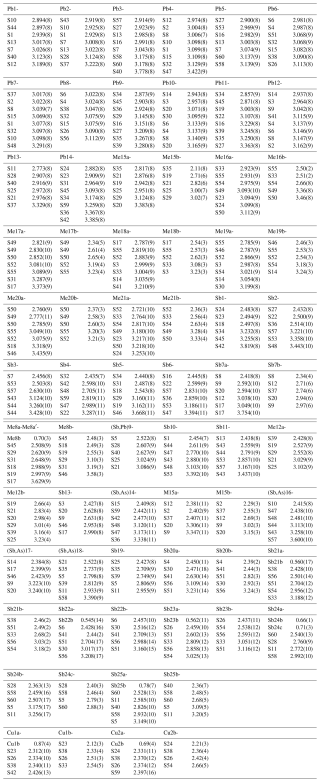

The asymmetric unit of launayite (Fig. 3) contains 48 cation and 60 anion sites. The metal sites consist of 21 Pb, 25 Sb, and 2 Cu positions. In total, 7 Pb sites are mixed with As (Me15 to Me21): 1 Sb site is mixed with Pb[(Sb,Pb)9], 4 Sb sites are mixed with As [(Sb,As)14, (Sb,As)16, (Sb,As)17, and (Sb,As)18], and 10 Sb sites are split (Sb7, Me8, Me12, M15, and Sb20–Sb25). Cu sites, Cu1 and Cu2, are both split as well (Table 3), and their CD and BVS suggest that Ag is not present at these sites. There are no As-dominant sites present in the structure. Although the (Sb,As)17 site contains a significant amount of As (Sb0.57As0.43), arsenic is not featured in the ideal formula of launayite.

Final refinement led to R1=0.0946 for 11 471 unique reflections. The resulting structural formula obtained from SCXRD study for the asymmetric unit, Cu2Pb20.330Sb23.024As2.689S60, Z=4, is close to the EMPA empirical formula, Cu2.078Ag0.059Tl0.057Pb20.404Sb22.830As2.772S59.80. The validation of refinement process is given in the Supplement as S2_checkcif_launayite.pdf file.

Table 3Site populations, occupancies, fractional coordinates, thermal parameters, coordination (CN), charge distribution (CD) values, and bond valence sums (BVSs) for launayite.

* Ref is the charge of the site obtained from refinement, whereas CD and BVS represent charge distribution and bond valence sum values, respectively, calculated for the cation sites with the program ECoN21 (Ilinca, 2022).

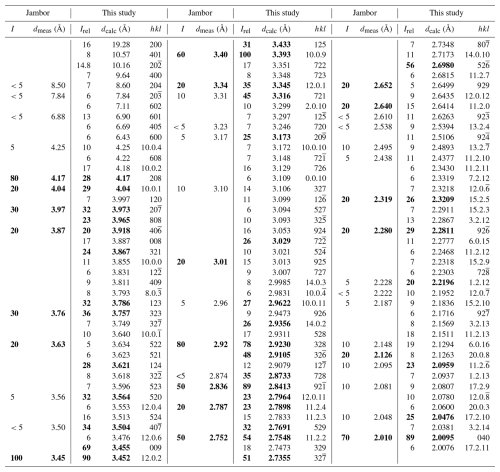

A comparison between the experimental X-ray powder diffraction data (Jambor, 1967b) and the calculated pattern using VESTA 3 (Momma and Izumi, 2011), based on the launayite crystal structure in Debye–Scherrer geometry with Cu Kα radiation (λ=1.540598 Å), is presented in Table 5 and shows a good agreement.

Table 5Comparison of experimental X-ray powder diffraction data (Jambor, 1967b) with calculated values from the launayite crystal structure (this study). Relative intensities are scaled to Imax = 100. Diffraction maxima with intensities ≥ 20 are highlighted in bold.

The theoretical pattern was calculated using VESTA 3 (Momma and Izumi, 2011) in Debye–Scherrer configuration employing Cu Kα radiation (λ=1.540598 Å), fixed slit,

and no anomalous dispersion. Unit cell parameters, space group, atom positions, site occupancy factors, and equivalent displacement factors from the crystal-structure

determination were used.

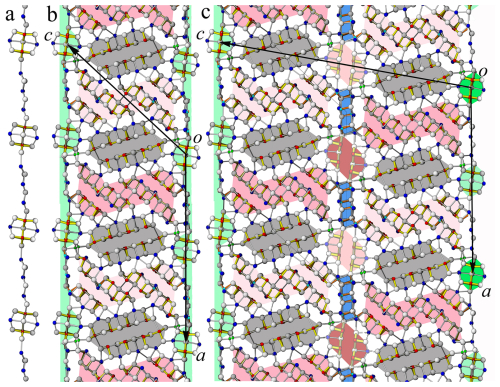

The launayite crystal under investigation is built from distinct modulated domains which can be derived from a common simplified parent structure with symmetry and b∼4 Å (4 Å being the approximate edge length of an MS6 octahedron in sulfosalt structures). The model of this simplified structure was generated by halving the b axis, increasing the symmetry, merging duplicate atoms, removing minor positions, and moving the atoms onto the reflection planes at y=0 and , respectively. Henceforth basis vectors and hkl indices will be given with respect to this parent structure.

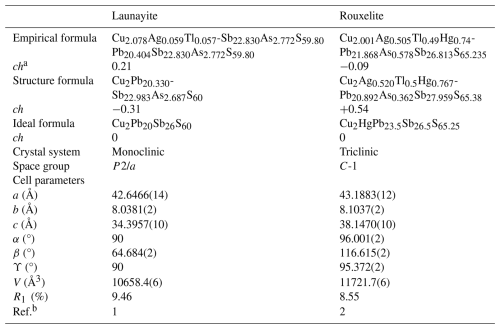

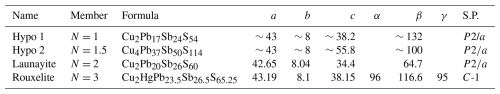

The parent structure of launayite is closely related to the b∼4 Å parent structure of rouxelite (Orlandi et al., 2005; Topa et al., 2025), with isomorphic symmetry. The cell parameters of the parent structures are compiled in Table 6.

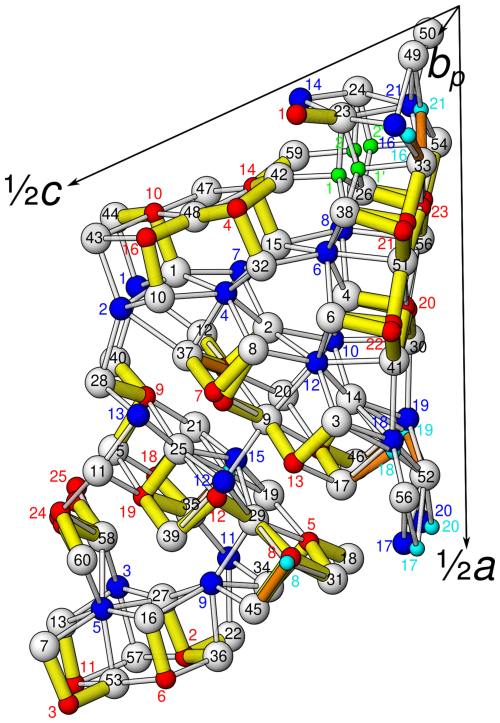

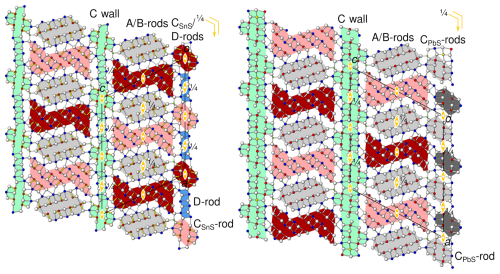

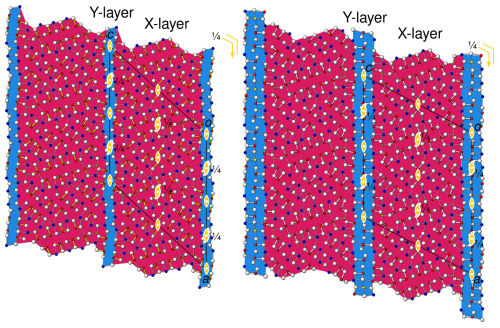

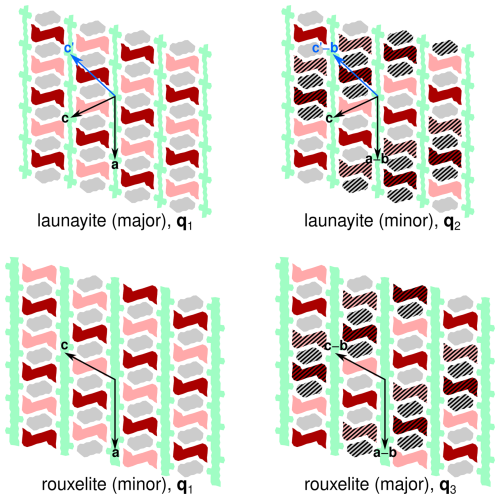

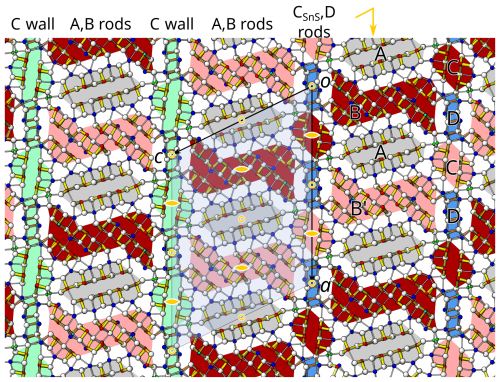

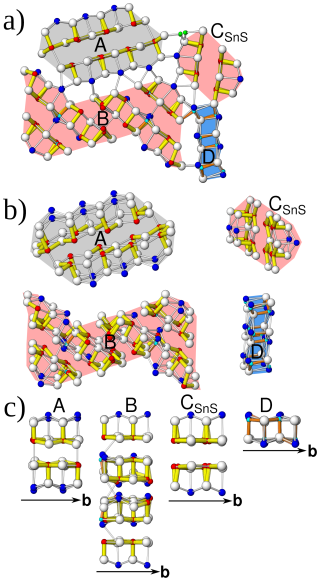

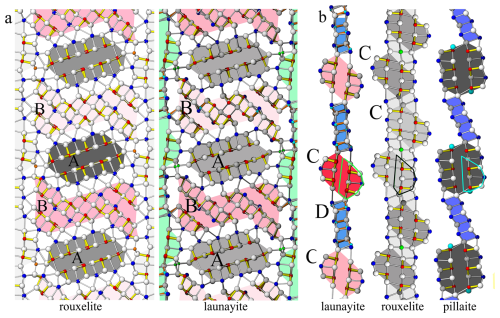

Figure 4The simplified parent structures of (left) launayite and (right) rouxelite viewed along the monoclinic axis [010] (b∼4 Å). Atom colouring: white for S sites, blue for Pb sites, red for Sb sites, green for Cu sites. The modules according to the boxwork description are marked by coloured backgrounds: PbS-like rods (A, CPbS) are grey, SnS-like rods (B, CSnS) are red, the two-sheet D rods are blue, and the C walls are green. Different shades indicate an additional translation of of the B and C rods. Symmetry elements are indicated by the standard symbols.

A boxwork description of rouxelite was first given by Orlandi et al. (2005), then by Makovicky and Topa (2009), and was later improved by Topa et al. (2025). In such a description (Fig. 4), both structures are defined by wall-like modules (the C layers, green in Fig. 4) parallel to (001) and limiting portions of alternating rod-like modules: PbS-based A modules (grey in Fig. 4) and SnS-based B modules (red in Fig. 4). For an introduction to PbS-like and SnS-like modules, see e.g. Makovicky (1993). From a structural point of view, extending in the [010] direction, the A and B rods in the parent structures of launayite and rouxelite can be regarded as isotypic. They possess and rod group symmetry (the subscript “b” in the Bravais symbol indicates the direction with translational symmetry), respectively, and together form A/B layers extending in the (001) plane with layer group symmetry. The C-centring of the space group corresponds to a translation by . For the A rod, which is located on a 21-screw rotation axis, translation by is equivalent to a 2-fold rotation about [010]. In contrast, the B rods are symmetric by 2-fold pure rotation, which means that their origin may be located on either y=0 or y=0.5. The C-centring exchanges the origin as indicated by different shades of red in Fig. 4.

Figure 5Interpretation of the simplified parent structures of (left) launayite and (right) rouxelite as a pair of merotypes with common X layers (red) and differing Y layers (blue). Atom colours and symmetry elements as in Fig. 4.

Table 6Comparative data for launayite from Taylor Pit, Madoc, and rouxelite from the Monte Arsiccio mine for Z=4.

a ch charge balance values calculated as (Σcation valence − Σanion valence) using apfu values. b [1]: this work; [2]: Topa et al. (2025)

Even though the C walls likewise feature layer group symmetry in launayite and rouxelite, they are structurally fundamentally different. Notably, in rouxelite, they are formed by three cation–anion planes, whereas in launayite they are only two planes wide. Thus, launayite may be regarded as an inferior (N=2) homologue of rouxelite (N=3). This is reflected by the C-layer-to-C-layer distance, which is derived from csin (β), being distinctly smaller in launayite (ca. 31 Å) than in rouxelite (ca. 34 Å). Accordingly, the cell volume is reduced by ca. 9 % (see Table 6). Moreover, the rouxelite C walls possess octahedrally coordinated Hg atoms (with minor Ag substitution) at the positions and characteristic rods of symmetry, where the lone pairs of one-sidedly uncoordinated S atoms point towards the 21 axis. The precise nature of these rods is not yet established, as they might contain minor amounts of O and/or feature S vacancies (for details see Topa et al., 2025). Both features are missing in launayite. In both cases, out-of-phase protuberances add short fourth and third cation–anion layers, respectively.

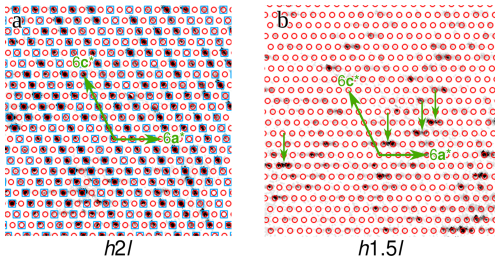

Figure 6Reciprocal space sections of the launayite crystal under investigation at (a) k=2 and (b) k=1.5 (with respect to the parent 4 Å structure). Reflections of the parent structure are marked by blue squares, and those of the major q1 superstructure are marked by red circles. Examples of q2 superstructure reflections are indicated by small green arrows in panel (b).

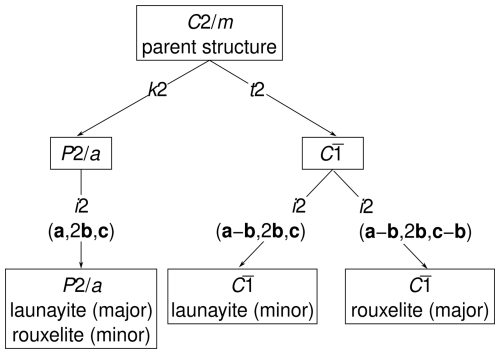

Figure 7Symmetry relationship between the simplified parent structures of launayite and rouxelite and the three observed superstructures.

For deeper insights into the difference between the C walls, it is useful to adopt a rod-based perspective. In rouxelite, the C walls have been decomposed into PbS-based C rods by Topa et al. (2025), as shown in Fig. 4 (right). To avoid confusion between the C wall and C rods, the meaning will henceforth always be specified. Moreover, we will indicate the archetype in the subscript and designate them as CPbS rods. The CPbS rods are located on general positions of the parent structure and can be seen as two double layers related by a 21-screw rotation resulting in pseudo-symmetry. Adjacent CPbS rods in rouxelite are connected by the Hg (+ minor Ag) and S rods with an additional Pb position (see uncoloured background in Fig. 4, right) described above. CPbS rods connected by Hg are at the same position with respect to [010], and those connected by the S rods are translated by .

Launayite features rods which in projection along [010] look practically identical to the CPbS rods in rouxelite (Fig. 4, left). However, here the double layers are related by 2-fold pure rotation, making these rods of the SnS kind ( symmetry, as opposed to in in rouxelite). Hence, these rods will be designated as CSnS rods. While in the parent structure of rouxelite, the CPbS rods are located on a general position, the CSnS rods in the parent structure of launayite are located on 2/m. Moreover, launayite features D rods with symmetry, which alternate with the C rods (blue background in Fig. 4, left). Since the D rods are only two atom sheets wide, they cannot be said to be of the PbS or SnS archetype (Makovicky and Topa, 2009). Observe that the combination of the symmetries of the CSnS rods and D rods in launayite (and of the CPbS rods, Hg (+ minor Ag) rods, and S rods in rouxelite) both result in symmetry of the C walls. Their structures are, however, fundamentally different. These comparisons show that the rod-based approach is superior for the structural comparisons in this family of minerals.

A consequence of the different location of the symmetry elements of the C walls in launayite (in CSnS and D rods) and rouxelite (between CPbS rods) is that if one A/B layer is fixed, in the adjacent A/B layer the positions of the A and B rods are exchanged; i.e. the adjacent A/B layer in rouxelite is shifted by ca. in launayite vs. rouxelite, which results in a distinctly more acute β angle in launayite (see Table 5). A further consequence of the shifted A/B layers is that the protuberances of the C walls are located next to the 2 axes in launayite but halfway between the 2 and 21 axes in rouxelite (see Fig. 4).

At the interface between A rods, B rods, and C walls, Cu atoms are located in tetrahedral coordination in both cases.

In summary, the simplified parent structures of launayite and rouxelite are built of isotypic A/B layers and fundamentally different C walls. Thus, they can be considered members of a family of merotypes (Ferraris et al., 2008), a generalisation of polytypes, where members of a family share only a part of the layers and where other layers may differ.

The description above was given with respect to modules of PbS- and SnS-like archetype structures. From a polytype/merotype approach, a different picture is obtained. Thereto, we consider the features/atomic positions that both structures have in common: foremost, the A/B layers, but also the protuberances of the C walls and the tetrahedrally coordinated Cu atoms. These are combined to layers X with symmetry, as shown with a red background in Fig. 5. The remaining atoms are attributed to layers Y, again with symmetry (blue background in Fig. 5), which correspond to the C walls without the protuberances. Here, from a symmetry point of view, both approaches are equivalent, and henceforth we will stick to the crystal-chemical interpretation. In other cases, though, both may lead to fundamentally different descriptions, as we have shown for owyheeite (Stöger et al., 2023).

Launayite and rouxelite not only share structural features, but their diffraction patterns likewise show similarities. While in both cases the reflections corresponding to the parent structure are strong and well defined (Fig. 6a, blue squares), they possess additional superstructure reflections in the planes, which indicate a doubling of the b axis (Fig. 6b) and which can be assigned to multiple domains in both cases.

The major domain of the launayite crystal under investigation is described by a modulation wave vector , indicated by red circles in Fig. 6b, which is compatible with monoclinic symmetry. Observe that there are twice as many reflections of this domain in the planes as in the k=n planes because the former contains first-order satellites from both adjacent planes. The second-order satellites, which would appear at places h+k odd in the k=n planes, are not observed (see red circles in Fig. 6a), which explains an excessive number of unobserved reflections in the structure refinements. Thus, in contrast to what one might infer from the -component of the q1-vector, this structure is a 4-fold superstructure because the second-order satellites are located at the systematic absences of the space group.

Two minor twin domains can be described as using the pair of modulation wave vectors and . These two domains are triclinic 2-fold superstructures. Examples of such reflections are indicated in Fig. 6b by black arrows.

The launayite structural data presented here are based on the q1 monoclinic structure. The same superstructure was observed for rouxelite, though as a minor domain (Topa et al., 2025). The dominant domains of rouxelite were a pair of triclinic twin domains with modulation wave vectors and .

The symmetry relationships of the launayite and rouxelite domains with their parent structures are shown in Fig. 7. To show the common and distinct superstructure types, the structures of launayite and rouxelite are combined in the same family tree, even though the parent structures are technically not isotypic (but rather merotypes). The symmetry of the q1 superstructure is a klassengleiche (same point group, different lattice) subgroup of index 4 and type (left branch in Fig. 7). The symmetry descent can be decomposed into two klassengleiche steps of index 2: loss of the C-centring from to , followed by a doubling of the b axis. The latter can be more precisely designated as an isomorphic group/subgroup relationship, as not only the point group but also the affine space group type is retained (hence the code i2 in Fig. 7).

Figure 8Schematic representation of the origins of the A and B rods in the superstructures of launayite and rouxelite. Colours of the modules as in Fig. 4. A translation along b (with respect to the parent structure) is indicated by hatching. Basis vectors of the superstructures are indicated by arrows. Blue arrows show an alternative setting of launayite.

The symmetry of the q2 superstructure is a general (loss of point and translation symmetry) subgroup of index 4. It can be decomposed into a translationengleiche (different point group, same lattice) descent to the space group , followed by an isomorphic descent to a structure with lattice basis (middle branch in Fig. 7). Since we did not determine the structure of the q2 domain, we cannot rule out a loss of inversion symmetry to C1; however, there is no reason to assume that it exists. The q3 superstructure (major domain of rouxelite) is derived analogously, but there the lattice basis is (right branch in Fig. 7).

Figure 9The crystal structure of launayite, viewed along the b axis (∼8.04 Å). Atom colouring: white, S sites; blue, fully occupied and dominant Pb sites; red, fully occupied and dominant Sb-occupied sites; green, Cu sites. Two different rods, A (PbS-like) and B (SnS-like), coloured differently (grey, light red, dark red), alternate along the a axis and are flanked by C wall layers. The C walls may also be seen as composed by CSnS and D rods which alternate along the a axis. The short, strong Sb (red)–S bonds are indicated in yellow (Sb–S ≤2.75 Å), and long Sb (red)–S bonds are indicated in white (2.75 Å≤ Sb–S <3.3 Å). Cation–sulfur bonds longer than 3.4 Å for Pb and 3.3 Å for Sb are not indicated. Symmetry elements are indicated by the usual symbols in yellow: circles are symmetry centres at y=0, , and 1. Lens shapes are 2-fold axes running parallel to the b axis. The yellow wedge with an arrow is a glide reflection at y=0, , and 1. The dark colours and light colours indicate B modules related by 2-fold rotation.

To understand the formation of the different superstructures, it is crucial to note that by doubling the b axis, translation symmetry is lost and the A and B rods now possess two different potential origins which are schematised in Fig. 8 by hatching. In the q1 superstructure, the b components of the origins of all rods are equal. In the q2 and q3 superstructures (where the q vector possesses an a* component of ), the origins are shifted by b (of the parent structure) for each translation along the a axis of the parent structure. In the q3 superstructure (with an additional c* component of in the q vector), there is an additional shift along b when crossing the C wall.

Figure 8 highlights a fundamental issue with comparing modulations/superstructures of non-isotypic basic structures. An alternative setting of the launayite parent structure that still maintains comparability with rouxelite is . This setting is just as valid, though we decided against it, because the corresponding monoclinic angle β ∼ 131.9 ° is larger than 120 °. However, in that setting (see blue arrow in Fig. 8), the minor domain features an origin shift of b when translating along c, as in rouxelite, which means that in this setting the modulation wave vector is identical to the major domain of rouxelite. Thus, it makes little sense to compare modulation wave vectors in distinct structures.

In summary, the superstructures are caused by a doubling of the translation period of the A and B rods in the [010] direction, and the cell and symmetry are due to the distribution of the origins of the A and B rods in the structure.

The major q1 superstructure of launayite is shown in Fig. 9. The reflection symmetry is lost, and the layer group symmetries of the C walls and the A/B layers are reduced to . The rod groups of the A modules are reduced to pb-1 (loss of the 21-screw rotation), and those of the B modules are reduced to pb121 (loss of inversion). The latter therefore appear in two orientations with respect to inversion, indicated by different shading in Fig. 9. In contrast, in the q2 and q3 superstructures, all rotational symmetry is lost and only centres of inversions remain. For details, see our recent publication on rouxelite (Topa et al., 2025).

Observe that the major domain features the same 2/m point group as the parent structure; therefore modulation cannot be responsible for the twinning observed in the (Lau1) grain (see above). Since we only collected diffraction data of an untwinned crystal (Lau2), the twin law cannot be stated unambiguously. However, in rouxelite we observed twinning by reflection at (100). We suspect that the same is true for launayite. This twinning suggests a reversal of the orientation of the A/B layers with respect to [100], which can be rationalised by partial [100] reflection symmetry of the halved C walls: given a C wall, the adjacent A/B layer can be reflected at [100] without major distortions.

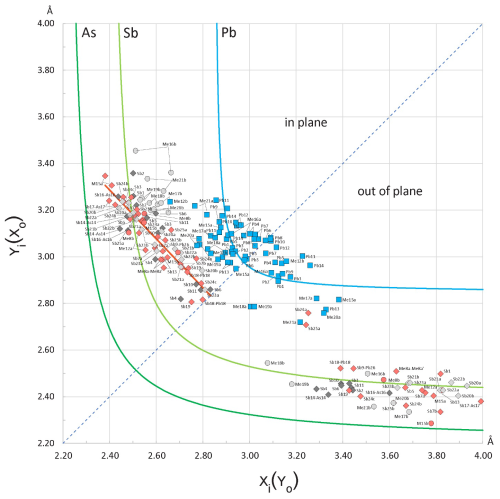

Figure 10Plot of the opposing bond pairs for the Pb(± Sb,As) and Sb(± As,Pb) coordination polyhedra in the crystal structure of launayite, against element-specific bond-length hyperbolae. For the “in-plane” bonds, the shorter distances (xi) are plotted along the abscissa, while for the “out-of-plane” pairs, the shorter distances (xo) are plotted along the ordinate. The red segment represents the regression () approximating the linear distribution of Sb “in-plane” bond pairs. The “in-plane” and “out-of-plane” bond pairs of Sb are plotted with lozenges of different colours according to their host module: A modules, dark grey; B modules, pink; C modules, light grey (see Fig. 4). Bond pairs for As sharing split positions are plotted with circles. The dotted diagonal corresponds to equal opposing bonds.

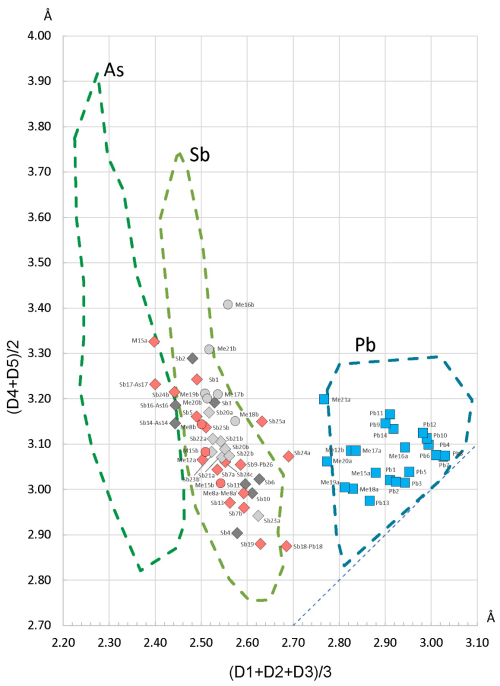

Figure 11The enhanced Armbruster–Hummel (Armbruster and Hummel, 1987; Topa et al., 2025) diagram modified to account for the chemical content of launayite. The diagonal dotted line (down at right) represents regular polyhedra where the two mean values are equal. The bond lengths in ascending order are denoted as D1, D2, D3, D4, and D5. The colouring of lozenges (Sb) and circles (As) reflect their host module (dark grey: Module A; pink: Module B; light grey: Module C).

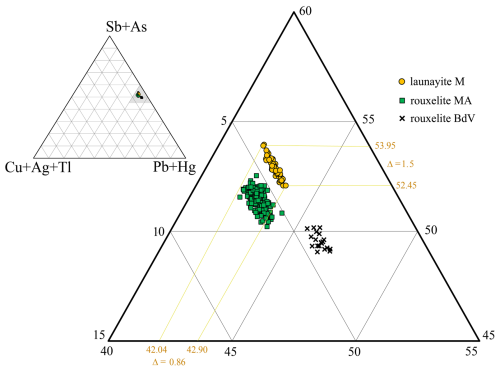

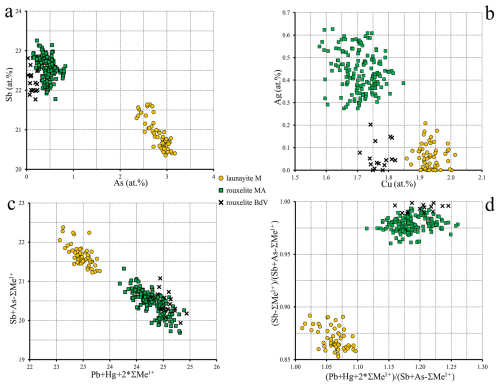

Figure 12Ternary plot in the system (Sb,As) – (Ag,Cu,Tl) – (Pb + Hg) for launayite from Madoc (M), rouxelite from the Monte Arsiccio mine (MA), and rouxelite from Buca della Vena mine (BdV) (Topa et al., 2025), showing their close but distinct positions. Chemically and structurally, Hg is present only in rouxelite, and Cu is essential for both minerals. Silver, Tl, and As are present in launayite but have no structural relevance. Note the “inclined line” shape of the launayite group of points: to a narrow Me1+ variation corresponds to a larger Me3+ variation and to a smaller Me2+ variation, indicating that Sb → As substitution is stronger than 2 Pb (Ag,Tl,Cu substitution.

Figure 13Binary plots of relevant pairs of element content (a, b), expressed in at. % values, and of two combinations (c, d) of ΣMe2+ vs. ΣMe3+ ratios for chemistries of launayite and rouxelite. Me1+ does not contain Cu. In all these representations, launayite and rouxelite compositions are clearly separated.

Given the intricate nature of launayite's crystal structure, the proposed cation distributions were evaluated using element-specific bond-length trends, following the approach of Trömel (1980) and Berlepsch et al. (2001a, b). This technique has been applied recently to the crystal structure of rouxelite from Monte Arsiccio Mine (Topa et al., 2025), which serves as a point of comparison with launayite. The procedure involves comparing pairs of contrasting bond lengths – those lying roughly within a plane and those extending above and below it – found in coordination octahedra and in mono-capped trigonal prisms (or split octahedra). The “in-plane” bonds correspond to equatorial positions (such as the shared base of two opposing pyramids or the base of a capping pyramid), while the “out-of-plane” bonds point toward axial ligands, more or less perpendicular to these “planes” which run parallel to the [010] zone axis and share the same orientation as the well-developed lone electron micelles.

The resulting x–y scatter plot (Fig. 10) reveals that the Pb-bearing capped prisms generally plot near the diagram's diagonal, indicating only minor disparities between paired bond lengths in the plane. In contrast, greater deviations from the ideal Pb curve are observed for the axial bonds, likely reflecting local distortions caused by adjacent semimetal polyhedra or positional splitting of the central cation.

Similar to the findings in rouxelite (Topa et al., 2025), the bond pairs within Sb-centred octahedra do not conform to the expected hyperbolic trend. Instead, they follow a nearly linear pattern intersecting the Sb curve, implying that the sums of the opposing in-plane bond lengths are consistently maintained constant (roughly between 5.6 and 5.7 Å). This supports a model of highly symmetrical in-plane ligand arrangements which are aligned with the crystallographic b axis.

The Armbruster–Hummel plot (Armbruster and Hummel, 1987) shown in Fig. 11 (used to distinguish between Sb- and Pb-dominated sites by plotting the mean of the three shortest bond lengths against the next two) displays a clear separation between the two types of coordination environments.

The resulting structural formula obtained from the SCXRD study for the asymmetric unit, Cu2Pb20.31Sb23.028As2.662S60, Z=4, is close to EMPA empirical formula, Cu2.078Ag0.059Tl0.057Pb20.404Sb22.830As2.772S59.80. The resulting ideal formula Cu2Pb20(Sb,As)26S60 (Z=4) confirms the stoichiometric formula given by Moëlo (1983). Launayite undergoes limited homovalent and heterovalent substitutions, such as Sb As3+ and 2Pb MeMe1+, where Me3+ is Sb and As; where Me1+ is Ag (0.059 apfu), Tl (0.057 apfu), and Cuextra (0.078 apfu); and where Cuextra is (Cu − 2).

The ternary plot (in atomic percent) in the (Cu + Ag + Tl) − (Pb + Hg) − (Sb + As) system (Fig. 12) based on all measured points from Buca della Vena (#20) and Monte Arsiccio (#171) from Topa et al. (2025), as well as launayite from this work (Table 3), illustrates a clear separation between the different groups in terms of Me1+, Me2+, and Me3+ content. Note that the “inclined narrow line” shape of the launayite data points to a narrow Me1+ variation together with a larger Me3+ variation and smaller Me2+ variation. This indicates that Sb → As substitution is stronger than 2 Pb (Ag,Tl,Cu (Sb,As)3+ substitution, which is not important in launayite. Chemically and structurally, Hg is present only in rouxelite, but Cu is essential for both minerals. Chemically, Ag, Tl, and As are present in launayite and rouxelite but bear no relevance for the ideal formula. Whether As stabilises launayite remains to be seen. No distinct position of Ag and Tl could be located by x-ray diffraction in launayite.

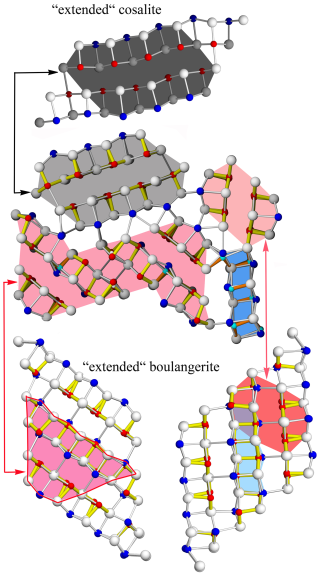

Figure 14The A, B, CSnS, and D rods of launayite, as cut-outs from PbS-like “extended cosalite” for A rod and SnS-like “extended boulangerite” for B, CSnS, and D rods. Note that “extended cosalite” (four Pb polyhedra instead of natural three Pb polyhedra) is a 4 Å and that boulangerite can present an orthorhombic (with 4 Å) and a monoclinic (with 8 Å) variant. The structural module type B is a cut-out from a hypothetical “extended” boulangerite rod (four Pb polyhedra instead of natural three Pb polyhedra). For cosalite (4 Å), crystal structure anion and cation sites, sitting on different levels (0 and or and ) along 4 Å axes, are coloured differently (bright and dark).

Figure 15(a) Module topology of launayite viewed down [010]. (b) Modules viewed slightly inclined to [010] showing connectivity. (c) Rods viewed perpendicular to [010] showing the archetype: A rod, PbS-like (grey); B and CSnS rods (red), SnS-like; D rod, undefined (blue).

Several binary plots (in atomic percent) using the same set of data points as described above are presented in Fig. 13a–d. These plots reveal clearly distinct chemical compositions for the two minerals, along with the internal compositional variations within each. Figures 12 and 13c show clear trends that indicate a substitution of Pb with (Sb,As) without a change in Me1+. This trend is very small, spanning ±0.43 Pb atomic % and ±0.75 (Sb,As) atomic %, and we have not been able to identify a known substitution mechanism or propose how the charge balance for this substitution occurs. Table 7 shows mixed positions which could be interpreted as possible candidates for such a substitution mechanism; however, we have no evidence for the mechanism of this very limited substitution or for how charge balance occurs.

Empirical, structural, and ideal formulae of launayite and rouxelite, along with their unit cell parameters, are presented in Table 6. The unit cell volume of rouxelite is larger than that of launayite, and substitutional mechanisms are more pronounced in rouxelite than those in launayite, owing to its wider C walls as described above.

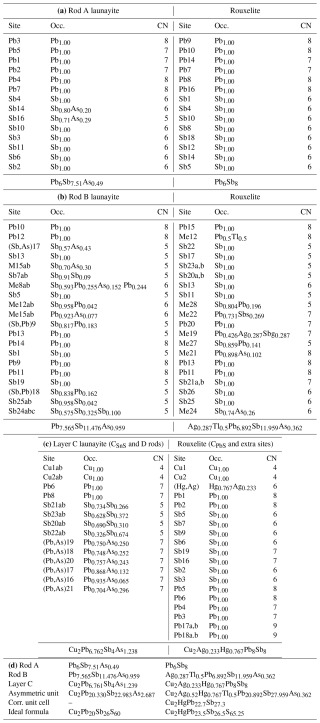

Table 7Independent sites and occupancies by rod type in the crystal structures of launayite from Taylor Pit, Madoc, and rouxelite from the Monte Arsiccio mine, for Z=4.

Independent sites and their occupancies by rod type (A, B, C, and D) in the crystal structures of launayite from Taylor Pit, Madoc, and rouxelite from the Monte Arsiccio mine are compared in Table 7. An overview of the modular structures of both minerals are given in Fig. 9; detailed interpretation of the rods in launayite is shown in Figs. 14 and 15. The A rod in both minerals contains 14 anion sites and has almost the same chemistry: Pb6Sb7.51As0.49 in launayite and Pb6Sb8 in rouxelite. The B rod, which includes 20 anion sites in both structures, also shows similar compositions: Pb7.565 Sb11.476As0.959 in launayite and Ag0.287Tl0.5Pb6.892Sb11.959As0.362 in rouxelite. The C walls contain 14 anions in launayite and have a distinct composition of Cu2Pb6.762 Sb4As1.238, in contrast to Cu2Ag0.233Hg0.767Pb8Sb8 in rouxelite, which includes 17 sites in the C wall owing to the additional Hg (with minor Ag) and Pb sites connecting the CPbS rods (see Fig. 4 for the decomposition of the C walls into rods).

Table 8Name, homologue number, ideal formula, unit cell parameters, and space group for hypothetical and natural homologue members (N) of the launayite–rouxelite series for Z=4. The ideal formula of rouxelite is debated, as it is unclear whether it contains O and/or S vacancies.

A comparison of the modular representations of the crystal structures of launayite and rouxelite (Topa et al., 2025) is shown in Fig. 16. The A and B rods in launayite structure are topologically identical to the A and B rods in rouxelite structure. In addition, the first row of anion sites, along with the additional Pb site layer flanking the A and B rods, is identical in both minerals (Fig. 16a). As noted above, the main structural difference lies in the second anion layer of the C wall in rouxelite (Fig. 16b). It is noteworthy that the CSnS rods in launayite have an SnS-like archetype, whereas the CSnS rods in rouxelite follow a PbS-like archetype despite being topologically identical (i.e., all rods consist of four anion layers, one exterior Pb site, and a double-layer interior with two Sb sites). The D rod in launayite is also present in the C wall layer of the pillaite structure (Meerschaut et al. (2001), together with an extended PbS-like rod (i.e., composed of four anion layers, with two exterior Pb sites and a double-layer interior with three Sb sites) (Fig. 16b).

Figure 16(a) Comparison of A and B rods in the major domain of launayite with those in the major domain of rouxelite. Different shading indicates additional translation along [010] (A and B rods in rouxelite) or 2-fold rotation about [010] (B rods in launayite). Topologically, the first row of metal sites plus the extra Pb sites flanking A and B rods are identical for both minerals. (b) Comparison of C wall layers characteristic of launayite (CSnS and D rods), rouxelite (CSnS rods and extra Hg (+ minor Ag) and Pb sites), and pillaite structures. Similarities and differences are described in the text.

A hypothetical C wall with N=1 can be constructed, as illustrated in Fig. 17a. Based on this, two hypothetical members can be envisioned, one with N=1 (Fig. 17b) and one with N=1.5, by combining one N=1 with one N=2 C wall in a single phase (Fig. 17c). The approximate unit cell parameter and ideal formulae for this series are shown in Table 8.

Mindat.org lists four additional localities for supposed launayite. The material from Mina Casualidad, Baños de Alhamilla, Pechina, Almería, Andalusia, Spain, does not contain any detectable Cu (Christian Rewitzer, personal communication, 2025) and therefore cannot correspond to launayite (Rewitzer et al., 2019).

The description of launayite from Dúbrava Sb deposit, Dúbrava, Liptovský Mikuláš District, Žilina Region, Slovakia (Adamus et al., 1993), similarly reports no presence of Cu in the chemical analysis. Only powder XRD was used, which makes the positive identification of a complex sulfosalt particularly challenging.

In the work by Nur et al. (2012), launayite is reported from the Baturappe prospect, Gowa Regency, South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia, with the only mention being “Very fine-grained silver and bismuth minerals… were also identified by SEM-EDX analysis; the minerals include bismuthinite… and launayite”. However, given the chemical complexity and similarity among related sulfosalt minerals, such a brief identification cannot be viewed as a reliable confirmation of launayite.

Lastly, launayite from the Cannington Mine (South32 Cannington), McKinlay, McKinlay Shire, Queensland, Australia, appears in a reference included in a symposium presentation (Bodon, 2018). However, no further details on this work were available to the authors of the present study. Overall, none of the reported localities provide clear evidence for the presence of launayite. While the first two can be excluded based on lack of Cu, the second two are questionable at best.

Based on our current research, we suggest that launayite should be regarded at present as a one-locality species.

After a long period during which the crystal structure and group affiliation of launayite remained unknown, we have now clarified both aspects and established its structural relationship to rouxelite, marking a new step in the understanding of complex Cu-Pb-Sb sulfosalts.

As we already observed for rouxelite, the launayite crystal under investigation is built of distinct superstructures. Such an edifice may be formed by exsolution of a high-temperature phase into two chemically distinct phases, or it may form from stress/strain caused by anisotropic thermal shrinking. Transmission electron microscopy and high-temperature diffraction measurements will be required to clarify the local structure and formation conditions of these intergrowths. In any case, these features highlight the inherent difficulty of classifying sulfosalt minerals based on their crystal structure.

The merotype relationship of the parent structures of rouxelite and launayite proves the importance of considering local symmetry and modularity when comparing crystal structures. A comparison of the global symmetry is insufficient.

Crystallographic data for launayite (cif and checkcif files) are available in the Supplement as S1 and S2.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/ejm-37-971-2025-supplement.

DT and FK initiated the project. DT performed EMPA analyses, and BS performed SCXRD experiments. GI performed CD and hyperbola calculations. All authors interpreted the data obtained. The article was written by DT with contributions from all co-authors.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors express their gratitude to Inna Lykova, Laura Smyk, and Michael Bainbridge from the Canadian Museum of Nature for the loaned MC 61602 sample containing launayite and to Goran Batic for help with the sample preparation. This work was performed in part at the Harvard University Center for Nanoscale Systems (CNS), a member of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure Network (NNCI), which is supported by the National Science Foundation. Also, we thank the Mineralogical and Geological Museum, Harvard University (MGMH#125654). We thank Sergey Krivovichev, Massimo Nespolo, Giovanni Ferraris, Yves Moëlo, and an anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments on the article.

This paper was edited by Massimo Nespolo and reviewed by Giovanni Ferraris, Yves Moëlo, and one anonymous referee.

Adamus, B., Jirnek, J., and Olovsk, U.: Launayit, nový minerál naložisku Sb rúd Dúbrava v Nízkych Tatrách, Min. Slovaca, Bratislava, 25, 73–74, 1993.

Armbruster, T. and Hummel, W.: (Sb,Bi,Pb) ordering in sulfosalts: Crystal-structure refinement of a Bi-rich izoklakeite, American Mineralogist, 72, 821–831, 1987.

Berlepsch, P., Makovicky, E., and Balić-Žunić, T.: Crystal chemistry of meneghinite homologue and related sulfosalts, Neues Jahrbuch der Mineralogie, Monatshefte, 3, 115–135, 2001a.

Berlepsch, P., Makovicky, E., and Balić-Žunić, T.: Crystal chemistry of sartorite homologues and related sulfosalts, Neues Jahrbuch der Mineralogie, Abhandlungen, 176, 45–66, https://doi.org/10.1127/njma/176/2001/45, 2001b.

Bodon, S.: Geology and genesis of the Cannington Ag-Pb-Zn deposit: Unravelling BHT Complexity, Garry Davidson symposium, CODES, University of Tasmania, 2018.

Ferraris, G., Makovicky, E., and Merlino, S.: Crystallography of Modular Materials, vol. 15 of IUCr Monographs on Crystallography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108768108025986, 2008.

Ilinca, G.: Charge Distribution and Bond Valence Sum Analysis of Sulfosalts – The ECoN21 Computer Program, Minerals, 12, 924, https://doi.org/10.3390/min12080924, 2022.

Jambor, J. L.: New lead sulfantimonides from Madoc, Ontario. Part I, Can. Mineral., 9, 7–24, 1967a.

Jambor, J. L.: New lead sulfantimonides from Madoc, Ontario. Part II, Can. Mineral., 9, 191–213, 1967b.

Jambor, J. L., Laflamme, J. H. G., and Walker, D. A.: A re-examination of the Madoc sulfosalts, The Mineralogical Record, March–April, 93–100, 1982.

Koziskova, J., Hahn, F., Richter, J., and Kozisek, J.: Comparison of different absorption corrections on the model structure of tetrakis(/m-acetato)-diaqua-di-copper (II), Acta Chimica Slovaca, 9, 136–140, https://doi.org/10.1515/acs-2016-0023, 2016.

Makovicky, E.: Rod-based sulphosalt structures derived from the SnS and PbS archetypes, Eur. J. Mineral., 5, 545–591, https://doi.org/10.1127/ejm/5/3/0545, 1993.

Makovicky, E., Topa, D., and Mumme, W. G.: The crystal structure of dadsonite, Can. Mineral., 44, 1499–1512, https://doi.org/10.2113/gscanmin.44.6.1499, 2006.

Makovicky, E. and Topa, D.: The crystal structure of sulfosalts with the boxwork architecture and their new representative Pb15−2xSb14+2xS36Ox, Can. Mineral, 47, 3–24, https://doi.org/10.3749/canmin.47.1.3, 2009.

Makovicky, E. and Topa, D.: Twinnite, Pb0.8Tl0.1Sb1.3As0.8S4, the OD character and the question of its polytypism, Zeitschrift für Kristallographie, 227, 468–475, https://doi.org/10.1524/zkri.2012.1491, 2012.

Makovicky, E., Topa, D., Tajjedin, H., Rastad, E., and Yaghubpur, A.: The crystal structure of guettardite, PbAsSbS4, and the twinnite- guettardite problem, Can. Mineral., 50, 253–265, https://doi.org/10.3749/canmin.50.2.253, 2012.

Meerschaut, A., Palvadeau, P., Moëlo, Y., and Orlandi, P.: Lead–antimony sulfosalts from Tuscany (Italy). IV. Crystal structure of pillaite, Pb9Sb10S23ClO0.5, an expanded monoclinic derivative of hexagonal Bi(Bi2S3)9I3, Eur. J. Mineral., 13, 779–790, https://doi.org/10.1127/0935-1221/2001/0013-0779, 2001.

Moëlo, Y.: Contribution à l'étude des conditions naturelles de formation des sulfures complexes d'antimoine et plomb (sulfosels de ), Signification métallogénique, Série Documents du BRGM, 55, 624 pp., 1983.

Moëlo, Y., Jambor, J. L., and Harris, D. L.: Tintinaite et sulfosels associes de Tintina (Yukon): La cristallochimie de la serie de la kobellite, Can. Mineral., 22, 219–226, 1984.

Moëlo, Y., Makovicky, E., Mozgova, N. N., Jambor, J. L., Cook, N., Pring, A., Paar, W. H., Nickel, E. H., Graeser, S., Karup-Møller, S., Balić-Žunić, T., Mumme, W. G., Vurro, F., Topa, D., Bindi, L., Bente, K., and Shimizu, M.: Sulfosalt systematics: a review. Report of the sulfosalt sub-committee of the IMA Commission on Ore Mineralogy, Eur. J. Mineral., 20, 7–46, https://doi.org/10.1127/0935-1221/2008/0020-1778, 2008.

Moëlo, Y., Guillot-Deudon, C., Evain, M., Orlandi, P., and Biagioni, C.: Comparative modular analysis of two complex sulfosalt structures: Sterryite, Cu(Ag,Cu)3Pb19(Sb,As)22(As–As)S56, and parasterryite, Ag4Pb20(Sb,As)24S58, Acta Crystallographica, B68, 480–492, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108768112034027, 2012.

Momma, K. and Izumi, F.: VESTA 3 for three–dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data, Journal of Applied Crystallography, 44, 1272–1276, https://doi.org/10.1107/S0021889811038970, 2011.

Nekrasov, I. Ya. and Bortnikov, N- S.: Condition of formation of lead and antimony sulfosalts and sulfostannates (experimental data), International Geological Review, 19, 395–404, 1977.

Nur, I., Idrus, A., Pramumijoyo, S., Harijoko, A., Watanabe, K., Imai, A., Ambosakka, S., Jaya, A., and Irfan, U. R.: Elemental Mass Balance of the Hydrothermal Alteration Associated with the Baturapp Epithermal Silver-Base Metal Prospect, South Sulawesi, Indonesia, 2012.

Orlandi, P., Moëlo, Y., Meerschaut, A., Palvadeau, P., and Léone, P.: Lead–antimony sulfosalts from Tuscany (Italy). VIII. Rouxelite, Cu2HgPb22Sb28S64(O,S)2, a new sulfosalt from Buca della Vena mine, Apuan Alps: definition and crystal structure, Can. Mineral., 43, 919–933, https://doi.org/10.2113/gscanmin.43.3.919, 2005.

Rewitzer, C., Hochleitner, R., and Fehr, T.: Mina Casualidad, Baňos de Alhamilla, Almeria, Spain, Mineral up, 5, 8–32, 2019.

Sheldrick, G. M.: SHELXT – Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination, Acta Crystallographica A, 71, 3–8, https://doi.org/10.1107/S2053273314026370, 2015a.

Sheldrick, G. M.: Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL, Acta Crystallographica C, 71, 3–8, https://doi.org/10.1107/S2053229614024218, 2015b.

Stöger, B., Göb, C., and Topa, D.: A fresh view on the structure and twinning of owyheeite, a rod-polytype and twofold superstructure, Acta Cryst., B79, 271–280, https://doi.org/10.1107/S2052520623004523, 2023.

Topa, D. and Makovicky, E.: The crystal structure of veenite. Mineralogical Magazine, 81, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1180/minmag.2017.081.003, 2017.

Topa, D., Stoeger, B., Keutsch, F. N., and Ilinca, G.: The 8 Å crystal structure and new crystal chemical data of rouxelite from the Monte Arsiccio mine, Apuan Alps, Italy, Eur. J. Mineral., 37, 591–616, https://doi.org/10.5194/ejm-37-591-2025, 2025.

Trömel, M.: Empirische Beziehungen zur Sauerstoffkoordination um Antimon(lll) und Tellur(lV) in Antimoniten und Telluriten, Journal of Solid-State Chemistry, 35, 90–98, 1980.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Chemical composition

- Single-crystal X-ray diffraction

- Parent structure

- Modulation

- Symmetry of the superstructures

- Major domain of launayite

- Site populations and bonds

- Crystal chemistry

- Detailed comparisons with rouxelite

- Launayite presence in other deposits

- Conclusion

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Review statement

- References

- Supplement

We conducted this research to gain an understanding of the unknown crystal structure of mineral launayite, which contains elements like antimony, copper, and lead. Using advanced X-ray techniques, we solved its crystal structure and discovered new details, such as unit cell parameters, symmetry, and substitutions. These findings provide accurate information about its relationship with rouxelite.

We conducted this research to gain an understanding of the unknown crystal structure of mineral...

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Chemical composition

- Single-crystal X-ray diffraction

- Parent structure

- Modulation

- Symmetry of the superstructures

- Major domain of launayite

- Site populations and bonds

- Crystal chemistry

- Detailed comparisons with rouxelite

- Launayite presence in other deposits

- Conclusion

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Review statement

- References

- Supplement