the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Coesite in garnet-quartzite of Orco Valley (Western Alps): an additional UHP unit in the records of deeply subducted meta-ophiolites

Stefano Ghignone

Mattia Gilio

Alessia Borghini

Emanuele Scaramuzzo

Ivano Gasco

Marco Bruno

We report the occurrence of coesite in a white mica–garnet-bearing quartzite from the metasedimentary cover of the meta-ophiolites exposed in the Orco Valley, Western Alps (Italy). This discovery is an addition to the growing number of ultra-high-pressure (UHP) meta-ophiolite localities in this portion of the Alps, and it indicates that the hosting rock has reached depths exceeding the quartz–coesite transition (≥ 2.8 GPa, 80–100 km) during subduction. Here, the petrological and mineralogical observations on garnet-hosted inclusions of the sample are reported and used to qualitatively constrain the metamorphic evolution of Orco Valley, also in relation to the other UHP units. At the scale of the Alpine fossil subduction zone, the UHP evidence occurs locally and discontinuously along strike, with exposures that are patchy rather than continuous (e.g., Lago di Cignana, Ala Valley, Susa Valley, Lago Superiore); however, when compared, the different units show similar metamorphic and structural features, suggesting similar P–T evolutions. This finding supports the interpretation that UHP meta-ophiolites of the Western Alps represent remnants of a former level that underwent comparable conditions in the coesite stability field within the oceanic slab. The frequent new identification of coesite likely reflects both improvements in micro-analytical techniques and increasing attention to smaller isolated inclusions.

- Article

(5935 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(7781 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Unraveling the early stages of the tectono-metamorphic evolution of orogenic belts is always challenging because late metamorphic events usually erase such information (see, e.g., Bucher and Grapes, 2009, and references therein). Garnet acts as a “treasure chest”, preserving crucial information on the prograde and peak stages of metamorphic evolution that are often absent in the rock matrix (Thompson et al., 1977; Krogh, 1982; Ferrero and Angel, 2018, and references therein). Garnet is capable of preventing the re-equilibration of ultra-high-pressure (UHP) index minerals (e.g., coesite) during exhumation, due to its wide P–T stability field (Carswell and Compagnoni, 2003; Baldwin et al., 2021, and references therein) and elastic properties, which allow it to preserve inclusions under residual pressure conditions (Angel et al., 2015). To decipher deep processes, coesite is one of the most coveted inclusions, as it provides direct evidence of UHP metamorphic conditions, likely developed during deep subduction of the slab (> 80 km; e.g., Chopin, 1984; Smith, 1984; Reinecke, 1991). Early studies identified coesite in garnet based on relatively large-sized (> 50 µm) crystals surrounded by quartz palisades and radial cracks (Chopin, 1984). The advent of advanced micro-analytical techniques, particularly micro-Raman spectroscopy, has revolutionized our ability to detect coesite, revealing its presence as tiny (2–50 µm) pristine single-crystal inclusions that may lack the “classic” microstructural features in host minerals. This methodology has greatly expanded the number of known coesite-bearing localities and opened new perspectives for identifying UHP rocks, especially for meta-ophiolites exhumed in orogenic belts (Zhang et al., 2002; Ghignone et al., 2020; Lardeaux, 2024). Although meta-ophiolites are ubiquitously distributed across all the main fossil subduction zones worldwide, to date, only a few have been confirmed to have reached UHP metamorphic conditions (e.g., Gilotti, 2013; Ghignone et al., 2024): the western Tianshan in China (Zhang et al., 2002) and some slivers of the Internal Piedmont Zone (IPZ) in the Western Alps, Italy (Reinecke, 1991; Ghignone et al., 2023, 2024; Maffeis et al., 2025). In IPZ, the first coesite discovery was reported by Reinecke (1991) in the meta-ophiolite suite at Lago di Cignana. Recently, coesite was detected in three other localities – the Lago Superiore Unit (Ghignone et al., 2023), Susa Valley (Ghignone et al., 2024), and Ala Valley (Maffeis et al., 2025) – substantially increasing the number of UHP slivers in IPZ. Interestingly, these localities have comparable peak metamorphic conditions and similar structural positions in the Alpine wedge (i.e., above the tectonic domes of Europe-margin-derived continental units: the Dora Maira, Monte Rosa, and Gran Paradiso; e.g., Chopin, 1984; Manzotti et al., 2022, and references therein). Based on these similarities, Ghignone et al. (2024) reinterpreted an existing model, originally proposed to explain recovered HP fragments in the Alps (e.g., Agard, 2021; Malusà et al., 2021; Herviou et al., 2022), and extended it to account for fragments that reached greater depths and were later detached from the downgoing oceanic plate.

In this study, we focused on a portion of the IPZ that overlies the Gran Paradiso continental unit in the Orco Valley. Here, a new finding of coesite in a white mica–garnet-bearing quartzite from the metasedimentary covers is reported. The coesite-bearing sample is characterized by petrological and mineralogical studies focusing on the inclusions trapped in garnet to constrain its metamorphic evolution and to compare it with other UHP localities. The presence of coesite in this new locality provides new evidence of UHP metamorphism in the meta-ophiolitic units detached from the subducted oceanic slab. Although the interrelations and continuity of UHP units remain uncertain, this study contributes to refining the architecture of the Western Alps.

The Western Alps represent a fossil subduction zone that involves two paleo-margins (Europe derived and Adria derived) and the interposed Alpine Neo-Tethys Ocean (Platt, 1986; Dewey et al., 1998; Marthaler and Stampfli, 1989; Michard et al., 1996; Jolivet et al., 2003; Handy et al., 2010; Malusà et al., 2015; Schmid et al., 2017; Ballèvre et al., 2020; Agard, 2021; Scaramuzzo et al., 2022). In the axial sector, consisting of the most deformed portions of the belt and recording the highest metamorphic conditions (Malusà et al., 2015; Ballèvre et al., 2020; Ghignone et al., 2020 and reference therein), continental and oceanic-derived rocks reached HP and UHP metamorphic conditions during subduction, preserving a polyphase tectono-metamorphic evolution (see, e.g., Lardeaux, 2024; Maffeis et al., 2025; Groppo et al., 2025, and references therein). The remnants of the subducted oceanic crust – the Piedmont Zone – are stacked in fragments between different continental crust units that are part of the European paleomargin below (see, e.g., Ballèvre et al., 2020, and references therein) and the Adria-derived units above (Agard, 2021, Agard and Handy, 2021; Malusà et al., 2021; Herviou et al., 2022, and references therein).

The Piedmont Zone is subdivided into external (EPZ) and internal (IPZ) portions, based on their metamorphic evolution, deformation, and structural position in the Alpine accretionary prism (Beltrando et al., 2010; Ghignone et al., 2021; Herviou et al., 2022). The IPZ records eclogite-facies metamorphism, with local UHP slices (Ghignone et al., 2021; Herviou et al., 2022). Peak P–T conditions vary across the domain, generally ranging from ∼ 2.5 to 3.2 GPa and from 480 to 605 °C (e.g., Groppo et al., 2009; Angiboust et al., 2012; Herviou et al., 2022; Ghignone et al., 2023; Maffeis et al., 2025).

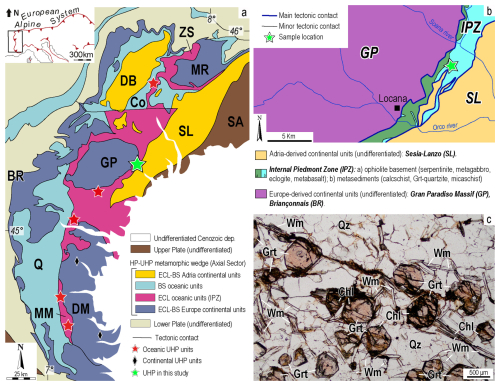

To date, the UHP units identified in the Western Alps belong to both continental and oceanic crust and are located in the axial sector of the Alps (Fig. 1a; Rosenbaum and Lister, 2005; Beltrando et al., 2010; Schmid et al., 2017; Ballèvre et al., 2020; Agard and Handy, 2021; Herviou et al., 2022). Among the IPZ meta-ophiolites, the coesite-bearing localities are (i) the Lago di Cignana Unit (Reinecke, 1991) in the northern sector (P=3.2 GPa and T=590–605 °C; Groppo et al., 2009); (ii) the Ala Valley in the middle (P=2.8–2.9 GPa and T=480–580 °C; Maffeis et al., 2025); (iii) the Susa Valley in the mid-south sector (P > 2.8 GPa and T ∼ 500 °C; Ghignone et al., 2021, 2024); and (iv) the Lago Superiore Unit, belonging to the Monviso Massif, in the southern sector (P=2.8–2.9 GPa and T=500–520 °C; Ghignone et al., 2023). The study area, the Orco Valley, is located in the same structural position as the meta-ophiolites of the Ala Valley on top of the Gran Paradiso continental dome. Between Locana and Ronco Canavese, close to Ribordone village, the IPZ is very narrow (a few km thick), and it is sandwiched between two continental crust units (Fig. 1b): the Gran Paradiso Massif below, with affinities to the European paleo-margin (Manzotti et al., 2018, and references therein), and the Sesia Lanzo Zone above, which was accreted to Adria (Schmid et al., 2004; Gasco et al., 2009; Gasco and Gattiglio, 2011) in the Cretaceous (e.g., Malusà et al., 2015). This portion of the IPZ comprises serpentinites, Mg-Al metagabbros, eclogites, metabasalts, and metasediments (e.g., quartzites, micaschists, marbles, and calcschists; Gasco et al., 2009; Gasco and Gattiglio, 2011). The metasediments host the coesite-bearing sample reported here.

Figure 1(a) Tectonic map of the Western Alps. Codes: BR = Briançonnais; Co = Combin Unit; DB = Dent Blanche; DM = Dora Maira; GP = Gran Paradiso; MM = Monviso Massif; MR = Monte Rosa; Q = Queyras Unit; SA = Southern Alps; SL = Sesia Lanzo; ZS = Zermatt-Saas, modified after Ballèvre et al. (2020) and Ghignone et al. (2023). (b) Simplified geological map of the study area, showing the meta-ophiolites of the Internal Piedmont Zone, sandwiched between the Gran Paradiso, below, and the Sesia Lanzo, above, modified after Gasco et al. (2009). The green star marks the sample location. The red stars indicate UHP oceanic localities: from the north to south Lago di Cignana Unit (Reinecke, 1991), Ala Valley (Maffeis et al., 2025), Susa Valley (Ghignone et al., 2024), and Lago Superiore Unit (Ghignone et al., 2023). The black diamonds indicate UHP continental localities from the north to south: the Chasteiran Unit (Manzotti et al., 2022) and Brossasco-Isasca Unit (Chopin, 1984). (c) Photomicrograph of the “garnet–muscovite-rich domain” in the studied samples. Garnets are euhedral and partially replaced by chlorite, and white mica flakes are concentrated within the quartz-dominated matrix. Mineral abbreviations after Warr (2021).

One sample was studied in thin and thick (100 µm) sections, double polished and uncovered, using optical microscopy, micro-Raman spectroscopy, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) equipped with an EDS detector. Garnet chemical compositions and the inclusion assemblages were analyzed to constrain the metamorphic evolution. The Raman spectra of mineral inclusions in garnet were collected using a Horiba LabRam HR Evolution spectrometer with a CCD detector from the University of Pavia (Italy). A holographic grating of 1800 grooves mm−1 and a 532 nm solid-state (YAG) laser were used. The spectrometer was calibrated with the silicon peak (520.6 cm−1). The spectra were collected with 30 s of acquisition time and four repetitions. The selected spectra were baseline corrected for the continuum luminescence background using a spline-fitting method. The peak positions were obtained from peak fits using pseudo-Voigt functions. Punctual analysis and high-resolution multispectral compositional maps were acquired with a JEOL JSM-IT300LV scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with an EDS Oxford Instruments X-act silicon drift detector at the Department of Earth Sciences (University of Torino, Italy). Working conditions were E=15 kV, I probe = 5 nA, EDS process time = 1 µs, 105 counts s−1, live time = 50 s, working distance = 10 mm for data points, dwell time 5 µs, pixel live time 3000 µs, and single frame for X-ray maps. The EDS-acquired spectra were calibrated in energy and intensity using measurements performed on a cobalt standard introduced into the vacuum chamber with the samples. Multispectral maps were quantified through Quantmap (Aztec Suite). Compositional point data were recalculated using the method proposed by Lanari et al. (2014, 2019) and combined according to the method proposed by Cossio et al. (2024).

The studied sample (VDO5, 45°27′ 56′′ N, 7°30′28′′ E) is a poorly deformed white mica–garnet-bearing quartzite. It displays a nearly granoblastic texture (Fig. 1c), dominated by medium- to fine-grained quartz (74 vol % modal), white mica (12 %, phengite 9 % and muscovite 3 %), and garnet (7 %), with minor epidote (5 %), chlorite (2 %), titanite (< 1 %), and plagioclase (< 1 %). Zircon, rutile, and apatite (< 1 %) are ubiquitously present as accessory phases.

Quartz is mostly subhedral, ranging from 100 to 500 µm in size. Garnet displays a well-defined euhedral shape, although many grains exhibit a rounded morphology and cracks. Its grain size varies from 100 to 500 µm. Garnet is locally replaced by chlorite, and it exhibits complex zoning, clearly visible by a marked difference in absorption colors under plane-polarized light (Figs. 1c, 2a). White mica is randomly oriented and occurs as fine-grained dispersed flakes (100 µm, Fig. 1c) as well as coarser grains (500 µm) associated with epidote, titanite, and apatite (Fig. S1). Most white mica grains are corroded and fractured, and some grains with low-silicon contents are intergrown with chlorite along cleavage planes. Epidote occurs with variable grain size (20–500 µm). It is generally subhedral, although locally it shows a well-preserved euhedral shape (Fig. S1). In some grains, allanite cores are preserved, displaying an intense chemical zoning. Chlorite grows topotactically (i.e., static growth) on garnet, preserving its euhedral shape. It also develops along cleavage planes in white mica (Fig. 1c). Titanite occurs as rare crystals with a grain size of 20–30 µm and typically forms by static overgrowth on rutile (Fig. S1e). Although rutile is the most common inclusion in garnet, it also occurs in the matrix as small (≈ 10 µm) subhedral crystals surrounded by titanite (Fig. S1e). Apatite has a rounded shape and a grain size between 10 and 300 µm; it rarely occurs in the matrix, but it is largely distributed as inclusions in garnet. Plagioclase is rare, and it usually occurs along garnet fractures (Fig. S1).

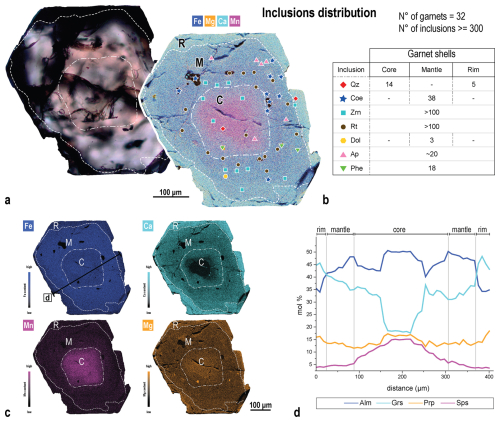

Compositional point analyses combined with multispectral maps reveal marked chemical zoning in garnet and white mica (Table S1). Garnet displays core, mantle, and rim domains with irregular and lobate boundaries (Fig. 2). Garnet cores show high almandine (Alm) content, and spessartine (Sps) and pyrope (Prp) contents decrease progressively from the center towards the mantle, whereas the grossular (Grs) content increases (Alm50−80, Grs3−25, Prp4−8, Sps10−23; Fig. 2c, d). Garnet mantles are characterized by a slight decrease of almandine and an increase of grossular towards the rims, whereas spessartine and pyrope are constant throughout (Alm56−80, Grs15−25, Prp4−9, Sps10−11; Fig. 2c, d). Garnet rims present a decrease of almandine content coupled with an increase in grossular towards the matrix, with constant pyrope and spessartine (Alm60−68, Grs6−28, Prp3−6, Sps1−10). The white mica in the matrix is dominantly phengitic and displays a zoning in silicon content ranging from Si > 3.50 apfu in the core to Si ∼ 3.30–3.49 apfu at the rim (Table S1). Muscovite (Si ∼ 3.00–3.20 apfu) locally develops along the rim of phengite grains (Table S1). The variation in silicon content in phengite is also observed in inclusions in garnet. Phengite with Si contents of ∼ 3.41–3.61 apfu is largely present, while the higher Si phengite (Si > 3.61 apfu) is present exclusively in the garnet mantle. Muscovite (Si ∼ 3.00–3.20 apfu) also occurs along garnet fractures. White mica is generally rich in potassium (K (K + Na) ∼ 90 %). Plagioclase is an albite (Ab) with composition Ab85An15 (Table S1).

Figure 2Chemical and mineralogical characterization of a representative garnet: (a) plane-polarized light (PPL) photomicrograph and summed compositional map (Fe, Mg, Ca, Mn) showing the distribution of the inclusions in garnet. The reference color for each phase is provided in (b). (b) Legend of inclusions and number of occurrences in each garnet growth domain. (c) X-ray maps of Fe, Mg, Ca, and Mn. The boundaries of the compositional zones are reported. On the Fe map, the black line corresponds to the trace of the compositional profile shown in (d). (d) Garnet compositional profile.

Garnet contains numerous mineral inclusions, which are often iso-oriented parallel to its crystal faces. The included phases are quartz, coesite, zircon, rutile, white mica, dolomite, and apatite (Fig. 2a). A summary of the analyzed inclusions, their spatial distribution, and abundance is shown in Fig. 2b. The combined chemical zoning of garnet and the distribution of inclusions guided the subdivision into core, mantle, and rim domains.

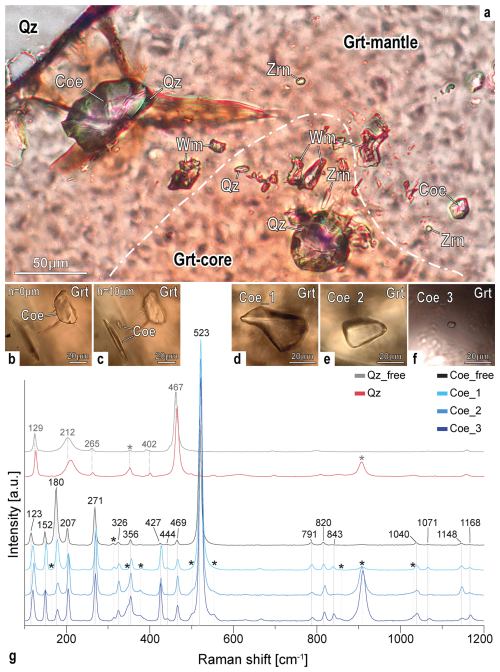

Coesite occurs exclusively in garnet mantles as subhedral crystals, typically ranging from 4 to 5 µm up to 50 µm in size (Fig. 3a–f). It often shows re-entrant angles and evidence of resorption (Fig. 3d); however, most inclusions appear pristine and elastically isolated as small and rounded, and are distant from cracks, other inclusions, and the surface of the host (Campomenosi et al., 2018; Mazzucchelli et al., 2018; Fig. 3a, f). Few coesite + quartz inclusions display radial cracks in the surrounding garnet, especially the bigger one near the garnet surface (Fig. 3a, b). Coesite occurs mostly as isolated crystals and rarely in clusters (Fig. 3b, c). The Raman spectra show the characteristic vibrational modes at 119, 152, 180, 207, 271, 326, 427, 444, 469, 521, 791, 820, 843, 1040, 1071, 1148 and 1168 cm−1 (Boyer et al., 1985; Fig. 3g). The main peak position depends on the elastic state of the inclusion: in non-elastically isolated inclusions, it is observed at 521 cm−1; in elastically isolated inclusions, it shifts to 523 cm−1 (Fig. 3g). Other peaks show no significant shifts in position, except for the peak at 119 cm−1, which shifts to 123 cm−1 in isolated inclusions (Fig. 3g).

Figure 3(a) A focus-stacked plane-polarized light (PPL) image showing a garnet with a coesite inclusion near the rim (with radial cracks; top left), a well-preserved coesite inclusion in the mantle (bottom right), and quartz inclusions in the core. (b, c) PPL photomicrographs of a cluster of coesite inclusions at different focal depths: (b) exposed coesite with radial cracks, (c) dipped isolated coesite. (d, e, f) PPL photomicrographs of coesite inclusions: (d) with signs of resorption, (e) with well-developed faces, (f) with a rounded shape. (g) Raman spectra of isolated quartz and coesite inclusions (d, e, f) compared with free quartz and coesite ones. Labeled peaks are assigned to shifted coesite and shifted quartz, whereas peaks marked with asterisks refer to the host garnet. Garnet peak values are 168, 315, 349, 379, 501, 553, 851, 910, and 1041 cm−1. Note that the peak near 1040 cm−1 is shared between garnet and coesite.

Quartz inclusions occur in garnet cores and rims; they vary in size from 5 to 20 µm and generally exhibit idiomorphic rounded morphology. The Raman spectra of quartz in the garnet core show a main peak around 470 cm−1, shifted by about 4–5 cm−1 compared to quartz in the matrix (464 cm−1). Other peaks also show consistent shifts to higher wavenumbers in core-hosted inclusions (Fig. 3g).

White mica occurs in all garnet domains in relatively large crystals (20–100 µm), with a shape either elongated and lamellar or rounded and fractured. Zircon (∼ 20 µm) is widely distributed throughout the garnet; it has a subhedral shape and occurs both isolated and clustered with rutile, oriented parallel to the garnet growth zoning. Dolomite is rare, and it occurs mainly in the garnet mantle as rounded inclusions of ∼ 20 µm. Due to the reduced number of inclusions, it is not certain whether the presence of dolomite is restricted to this garnet domain. Apatite is evenly distributed in all garnet domains; it has an euhedral shape and a size ranging from a few microns to 30 µm. Rutile also occurs in all garnet domains, with euhedral shapes and sizes between 4 and 30 µm. Larger crystals (> 50 µm) locally form bands oriented to the garnet growth zoning.

The study of inclusion assemblages, garnet chemical zoning, and petrographic features allows a qualitative reconstruction of the metamorphic evolution of the studied sample in three main metamorphic stages. In the absence of dedicated thermobarometric data, the metamorphic history proposed is provisional; however, the comparison with established P–T frameworks for the UHP meta-ophiolitic covers of the Western Alps is used as additional support for the data.

The first stage is defined by the spessartine-rich garnet core containing quartz, rutile, apatite, and white mica (Si > 3.41 apfu) inclusions. This mineral assemblage reflects early high-pressure mineral growth (P < 2.7 GPa; Ghignone et al., 2024), qualitatively comparable to the prograde evolution documented in the Lago di Cignana and Lago Superiore units (Reinecke, 1991; Ghignone et al., 2023). Garnet likely nucleated under high-pressure blueschist to eclogite facies conditions during progressive burial of the metasedimentary cover. The composition of these cores resembles the spessartine-rich UHP garnet cores in the micaschists described in the Susa Valley Unit (Ghignone et al., 2024).

The second stage corresponds to a metamorphic event in the coesite-eclogite facies, marked by the growth of the garnet mantle, with a distinct chemical shift from a spessartine-rich core to a more grossular-enriched composition, and by the entrapment of coesite within this domain. The occurrence of coesite only defines a minimum pressure around the quartz–coesite transition (P > 2.7 GPa; Ghignone et al., 2024). The Raman spectra of elastically isolated coesite inclusions show a slight shift of the peaks with respect to the non-elastically isolated ones, which might indicate a higher entrapment pressure (Groppo et al., 2016; Ghignone et al., 2023). However, the lack of reliable pressure-shift calibrations for coesite prevents quantitative pressure estimates with spectroscopic techniques. The observed mineral assemblage for this stage, defined by garnet mantle, coesite, phengite (Si > 3.6 apfu), rutile, and apatite, is consistent with UHP conditions reported for the Lago di Cignana and Lago Superiore units (Reinecke, 1991; Ghignone et al., 2023), around 2.8–3.2 GPa and 550–600 °C. The grossular-enriched mantle contrasts with the pyrope-rich mantles described in other UHP localities (Reinecke, 1991; Ghignone et al., 2023), suggesting subtle bulk-rock compositional effects.

The third stage is recorded by the growth of garnet rims that entrapped quartz inclusions. The presence of quartz rather than coesite in the garnet rim suggests a slight temperature increase during the first stages of decompression, as described in other parts of the IPZ (Ghignone et al. 2021; 2024; Herviou et al., 2022; Maffeis et al., 2025). The mineral assemblage observed for this stage is defined by garnet rim, quartz, rutile, apatite, and white mica (Si ∼ 3.41–3.51 apfu), indicating that the rock remained under high-pressure conditions compatible with the quartz-eclogitic facies. This exhumation trend broadly agrees with the warm decompression trajectories reported for other UHP units of the Western Alps (Ghignone et al., 2021, 2024; Maffeis et al., 2025).

The Si range in white mica (3.41 to > 3.61 apfu across the sample) outlines a prograde-to-exhumation trend consistent with phengite evolution described in the Lago di Cignana quartzites (phengite evolves from Phe I to Phe III; Reinecke, 1991) and Lago Superiore metasediments (phengite zone decreases from 3.4 to 3.6 apfu from prograde to peak metamorphic conditions; Ghignone et al., 2023).

A late re-equilibration stage in greenschist facies conditions is instead defined by muscovite, epidote, chlorite, albite, and titanite that statically replaced the eclogite-facies assemblage. These late-stage overprints record the final exhumation and are consistent with retrogressive conditions reported for the Lago di Cignana and Susa Valley units (≤ 0.6 GPa and 350–430 °C; Reinecke, 1991; Ghignone et al., 2024).

Overall, the studied sample records metamorphic evolution coherent with the regional Alpine framework, marked by progressive burial to UHP conditions and subsequent exhumation under high-pressure quartz-eclogite facies conditions, consistent with the metamorphic trajectories described for other localities of the IPZ (Herviou et al., 2022).

From the regional point of view, the IPZ in Orco Valley shares the same structural position as other coesite-bearing meta-ophiolitic localities, as they all occur above the eclogitized continental crust (Ghignone et al., 2023, 2024; Maffeis et al., 2025). These UHP units reached similar peak-P conditions ranging between 2.8–3.2 GPa and 500–600 °C (Groppo et al., 2009; Ghignone et al., 2023, 2024; Maffeis et al., 2025), and they have had a comparable metamorphic evolution, as discussed above. Following Ghignone et al. (2024), and in line with slice-detachment models previously proposed for the IPZ (Agard et al., 2002; Angiboust et al., 2014; Herviou et al., 2022; Locatelli et al., 2018; Malusà et al., 2015), these UHP localities can be interpreted as portions of the downgoing plate that were carried to greater depths than adjacent units before being detached. The P–T conditions for these fragments are consistent with the cold subduction geothermal gradient (∼ 6 °C km−1), already estimated for the IPZ subduction (Groppo and Castelli, 2010; Dragovic et al., 2020; Herviou et al., 2022). These observations suggest that the UHP localities either (i) represent remnants of a continuous level within the oceanic slab that reached UHP conditions during subduction, which was then detached and dismembered in fragments during exhumation or (ii) record a series of discrete UHP slices that detached and were underplated at different times along the subduction interface. Because geochronological coverage across these units is discontinuous, we defer an unequivocal interpretation between these two hypotheses. Previous studies propose that exhumation of Eocene eclogites in the Western Alps may have occurred in a single event (e.g., Malusà et al., 2011, 2015); however, in the absence of direct geochronological constraints, the timing – and therefore the most plausible detachment and exhumation mechanisms – remains debated. The newly identified coesite-bearing locality in Orco Valley adds a missing piece, extending the distribution of known UHP meta-ophiolitic fragments across the IPZ.

The identification of a new UHP unit relies on a preserved UHP mineral index, such as coesite. However, the preservation of coesite inclusions is influenced by several factors, such as the inclusion size, the location within the garnet host, and the volume of the surrounding garnet, which ensures elastic isolation and fluid availability (Schönig et al., 2019, 2021; Baldwin et al., 2021). Larger inclusions (∼ 50 µm) near garnet rims are frequently replaced by quartz and exhibit radial cracks in the surrounding garnet (Fig. 3a, b), while smaller, well-isolated inclusions are better preserved (Fig. 3a, f). It is possible that during decompression, the radial fractures may later be exploited by a fluid that promotes the total re-crystallization of the former coesite (Schönig et al., 2021). Therefore, the ability to detect coesite in a sample may depend strongly on the accuracy of identifying micrometric inclusions, as the larger, more exposed ones are typically the most affected by retrogression (Schönig et al., 2021; Taguchi et al., 2021). Consequently, coesite may commonly occur as inclusions in garnet and might often be overlooked when relying solely on optical microscopy (Compagnoni et al., 2024). The increasing use of micro-Raman spectroscopy is thus crucial for identifying UHP subduction signatures in other meta-ophiolitic units and refining our understanding of subduction dynamics in the Western Alps. Combining detailed mineralogical observations with quantitative geothermobarometry and geochronological studies will allow us to test whether the UHP fragments represent discrete, temporally distinct slices or remnants of a once more continuous domain within the Alpine subduction system.

All datasets are available upon request.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/ejm-37-927-2025-supplement.

Conceptualization: FB, SG, MG, AB, ES, and MB. Data curation: FB, SG, and MG. Investigation: FB, SG, MG, and ES. Methodology: SG, MG, ES, AB, FB, and MB. Supervision: MB. Validation: SG, MG, ES, AB, IG, and MB. Writing (original draft): FB, SG, MG, and AB. Writing (review and editing): FB, SG, MG, AB, ES, IG, and MB. All authors read and approved the final article.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We thank Chief Editor Reto Gieré, Associate Editor Pierre Lanari, the anonymous reviewer, and the reviewers Mahyra Tedeschi and Marco Malusà for their critical and constructive reviews. We are sincerely thankful to Jan Schönig for his review of an early version of the manuscript.

The research has been funded as follows: Stefano Ghignone, Marco Bruno, and Federica Boero were supported by research grants from the University of Torino, Ricerca Locale 2022 (Cdd. 21/07/2022); Alessia Borghini was co-funded by the National Science Centre (Poland) and the European Union Framework Program for Research and Innovation Horizon 2020 under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement no. 945339 (project no. 2021/43/P/ST10/03202); and Mattia Gilio was supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (Bonn, Germany) and by the project High-stress Earthquakes by Faulting in Deep Dry Rocks (THALES, PRIN-MIUR no. 2020WPMFE9 to G. Pennacchioni).

This paper was edited by Pierre Lanari and reviewed by Mahyra Tedeschi, Marco Giovanni Malusa, and one anonymous referee.

Agard, P.: Subduction of oceanic lithosphere in the Alps: Selective and archetypal from (slow-spreading) oceans, Earth Sci. Rev., 214, 103517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2021.103517, 2021.

Agard, P. and Handy, M. R.: Ocean subduction dynamics in the Alps, Elements, 17, 9–16, https://doi.org/10.2138/gselements.17.1.9, 2021.

Agard, P., Monie, P., Jolivet, L., and Goffé, B.: Exhumation of the Schistes Lustres Complex: In Situ Laser Probe 40Ar 39Ar Constraints and Implications for the Western Alps, J. Metamorph. Geol., 20, 599–618. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1314.2002.00391.x, 2002.

Angel, R. J., Nimis, P., Mazzucchelli, M. L., Alvaro, M., and Nestola, F.: How large are departures from lithostatic pressure? Constraints from host-inclusion elasticity, J. Metamorph. Geol., 33, 801–813, https://doi.org/10.1111/jmg.12138, 2015.

Angiboust, S., Langdon, R., Agard, P., Waters, D., and Chopin, C.: Eclogitization of the Monviso Ophiolite (W. Alps) and Implications on Subduction Dynamics, J. Metamorph. Geol., 30, 37–61, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1314.2011.00951.x, 2012.

Angiboust, S., Pettke, T., De Hoog, J. C. M., Caron, B., and Oncken, O.: Channelized Fluid Flow and Eclogite – Facies Metasomatism Along the Subduction Shear Zone, J. Petrol., 55, 883–916, https://doi.org/10.1093/petrology/egu010, 2014.

Baldwin, S. L., Schönig, J., Gonzalez, J. P., Davies, H., and von Eynatten, H.: Garnet sand reveals rock recycling processes in the youngest exhumed high- and ultrahigh-pressure terrane on Earth, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 118, e2017231118, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2017231118, 2021.

Ballèvre, M., Camonin, A., Manzotti, P., and Poujol, M.: A step towards unraveling the paleogeographic attribution of pre-Mesozoic basement complexes in the Western Alps based on U-Pb geochronology of Permian magmatism, Swiss J. Geosci., 113, https://doi.org/10.1186/s00015-020-00367-1, 2020.

Beltrando, M., Rubatto, D., and Manatschal, G.: From passive margins to orogens: The link between ocean-continent transition zones and (ultra) high-pressure metamorphism, Geology, 38, 559–562, https://doi.org/10.1130/G30768.1, 2010.

Boyer, H., Smith, D. C., Chopin, C., and Lasnier, B.: Raman microprobe (RMP) determinations of natural and synthetic coesite, Phys. Chem. Miner., 12, 45–48, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00348746, 1985.

Bucher, K. and Grapes, R.: The Eclogite-facies Allalin Gabbro of the Zermatt-Saas Ophiolite, Western Alps: a Record of Subduction Zone Hydration, J. Petrol., 50, 1405–1442, https://doi.org/10.1093/petrology/egp035, 2009.

Campomenosi, N., Mazzucchelli, M. L., Mihailova, B., Scambelluri, M., Angel, R. J., Nestola, F., Reali, A., and Alvaro, M.: How geometry and anisotropy affect residual strain in host-inclusion systems: coupling experimental and numerical approaches, Am. Mineral., 103, 2032–2035, https://doi.org/10.2138/am-2018-6700CCBY, 2018.

Carswell, D. A. and Compagnoni, R. (Eds.): Ultrahigh Pressure Metamorphism. EMU Notes in Mineralogy, 5, 508 pp., ISBN 963 463 6462, 2003.

Chopin, C.: Coesite and pure pyrope in high-grade blueschists of the western Alps: A first record and some consequences, Contrib. Mineral. Petrol., 86, 107–118, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00381838, 1984.

Compagnoni, R., Gilio, M., Ghignone, S., Scaramuzzo, E., Borghini, A., and Bruno, M.: Comment on “first finding of continental deep subduction in the Sesia Zone of Western Alps and implications for subduction dynamics”, Nat. Sci. Rev., nwae454, https://doi.org/10.1093/nsr/nwae454, 2024.

Cossio, R., Ghignone, S., Borghi, A., Corno, A., and Vaggelli, G.: A supervised machine learning procedure for EPMA classification and plotting of mineral groups, Appl. Comput. Geosci., 23, 100186, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acags.2024.100186, 2024.

Dewey, J. F., Holdsworth, R. E., and Strachan, R. A.: Transpression and transtension zones, in: Continental Transpressional and Transtensional Tectonics, edited by: Holdsworth, R. E., Strachan, R. A., and Dewey, J. F., Geol. Soc., London, Spec. Publ. 135, 1–14, 1998.

Dragovic, B., Angiboust, S., and Tappa, M. J.: Petrochronological close-up on the thermal structure of a paleo-subduction zone (W. Alps), Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 547, 116446, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2020.116446, 2020.

Ferrero, S. and Angel, R. J.: Micropetrology: Are Inclusions Grains of Truth?, J. Petrol., 59, 1671–1700, https://doi.org/10.1093/petrology/egy075, 2018.

Gasco, I. and Gattiglio, M.: Geological map of the middle Orco Valley, Western Italian Alps, Journal of Maps, 7, 463–477, https://doi.org/10.4113/jom.2010.1121, 2011.

Gasco, I., Gattiglio, M., and Borghi, A.: Structural evolution of different tectonic units across the AustroAlpine-Penninic boundary in the middle Orco Valley (Western Italian Alps), J. Struct. Geol., 31, 301–314, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsg.2008.11.007, 2009.

Ghignone, S., Balestro, G., Gattiglio, M., and Borghi, A.: Structural evolution along the Susa Shear Zone: the role of a first-order shear zone in the exhumation of meta-ophiolite units (Western Alps), Swiss J. Geosci., 113, 17, https://doi.org/10.1186/s00015-020-00370-6, 2020.

Ghignone, S., Borghi, A., Balestro, G., Castelli, D., Gattiglio, M., and Groppo, C.: HP-tectonometamorphic evolution of the Internal Piedmont Zone in Susa Valley (Western Alps): New petrologic insight from garnet + chloritoid-bearing micaschists and Fe-Ti metagabbro, J. Metamorph. Geol., 39, 391–416, https://doi.org/10.1111/jmg.12574, 2021.

Ghignone, S., Scaramuzzo, E., Bruno, M., and Livio, F.: A new UHP unit in the Western Alps: first occurrence of coesite from the Monviso Massif (Italy), Am. Mineral., 108, 1368-1375, https://doi.org/10.2138/am-2022-8621, 2023.

Ghignone, S., Gilio, M., Borghini, A., Boero, F., Bruno, M., and Scaramuzzo, E.: Mineralogical and petrological constraints and tectonic implications of a new coesite-bearing unit from the Alpine Tethys oceanic slab (Susa Valley, Western Alps), Lithos, 472/473, 107575, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lithos.2024.107575, 2024.

Gilotti, J. A.: The realm of ultrahigh-pressure metamorphism, Elements, 9, 255–260, https://doi.org/10.2113/gselements.9.4.255, 2013.

Groppo, C. and Castelli, D.: Prograde P-T evolution of a lawsonite eclogite from the Monviso meta-ophiolite (Western Alps): dehydration and redox reactions during subduction of oceanic FeTi-oxide gabbro, J. Petrol., 51, 2489–2514, https://doi.org/10.1093/petrology/egq065, 2010.

Groppo, C., Beltrando, M., and Compagnoni, R.: The P-T path of the ultra-high pressure Lago Di Cignana and adjoining high-pressure meta-ophiolitic units: insights into the evolution of the subducting Tethyan slab, J. Metamorph. Geol., 27, 207–231, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1314.2009.00814.x, 2009.

Groppo, C., Ferrando, S., Castelli, D., Elia, D., Meirano, V., and Facchinetti, L.: A possible new UHP unit in the Western Alps as revealed by ancient Roman quern-stones from Costigliole Saluzzo, Italy, Eur. J. Mineral., 28, 1215–1232, https://doi.org/10.1127/ejm/2016/0028-2531, 2016.

Groppo, C., Ferrando, S., Tursi, F., and Rolfo, F.: A New UHP-HP Tectono-Metamorphic Architecture for the Southern Dora-Maira Massif Nappe Stack (Western Alps) Based on Petrological and Microstructural Evidence, J. Metamorph. Geol., 43, 359–383, https://doi.org/10.1111/jmg.12812, 2025.

Handy, M. R., Schmid, S. M., Bousquet, R., Kissling, E., and Bernoulli, D.: Reconciling plate-tectonic reconstructions of Alpine Tethys with the geological–geophysical record of spreading and subduction in the Alps, Earth-Sci. Rev., 102, 121–158, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2010.06.002, 2010.

Herviou, C., Agard, P., Plunder, A., Mendes, K., Verlaguet, A., Deldicque, D., and Cubas, N.: Subducted fragments of the Liguro-Piemont ocean, Western Alps: Spatial correlations and offscraping mechanisms during subduction, Tectonophysics, 827, 229267, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tecto.2022.229267, 2022.

Jolivet, L., Faccenna, C., Goffe, B., Burov, E., and Agard, P.: Subduction tectonics and exhumation of high-pressure metamorphic rocks in the Mediterranean orogens, Am. J. Sci., 303, 353–409, https://doi.org/10.2475/ajs.303.5.353, 2003.

Krogh, E. J.: Metamorphic evolution of Norwegian country-rock eclogites, as deduced from mineral inclusions and compositional zoning in garnets, Lithos, 15, 305–321, https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-4937(82)90021-4, 1982.

Lanari, P., Vidal, O., De Andrade, V., Dubacq, B., Lewin, E., Grosch, E. G., and Schwartz, S.: XMapTools: A MATLAB©-based program for electron microprobe X-ray image processing and geothermobarometry, Comput. Geosci., 62, 227–240, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2013.08.010, 2014.

Lanari, P., Vho, A., Bovay, T., Airaghi, L., and Centrella, S.: Quantitative compositional mapping of mineral phases by electron probe micro-analyser, Geological Society Special Publication, 478, 39–63, https://doi.org/10.1144/SP478.4, 2019.

Lardeaux, J. M.: Metamorphism and linked deformation in understanding tectonic processes at varied scales, Comptes Rendus, Géoscience, Geodynamics of Continents and Oceans – A tribute to Jean Aubouin, 356/S2, 525–550, https://doi.org/10.5802/crgeos.204, 2024.

Locatelli, M., Verlaguet, A., Agard, P., Federico, L., and Angiboust, S.: Intermediate-Depth Brecciation Along the Subduction Plate Interface (Monviso Eclogite, W. Alps), Lithos, 320/321, 378–402, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lithos.2018.09.028, 2018.

Maffeis, A., Petroccia, A., Nerone, S., Caso, F., Corno, A., Bonazzi, M., Boero, F., Corvò, S., Ghignone, S., and Groppo, C.: Filling the gap in the UHP metamorphic record of the Liguro-Piemont Lower unit: insights on fluid-mediated formation of atoll garnets, Lithos, 498–499, 107981, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lithos.2025.107981, 2025.

Malusà, M. G., Faccenna, C., Garzanti, E., and Polino, R.: Divergence in subduction zones and exhumation of high pressure rocks (Eocene Western Alps), Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 310, 21–32, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2011.08.002, 2011.

Malusà, M. G., Faccenna, C., Baldwin, S. L., Fitzgerald, P. G., Rossetti, F., Balestrieri, M. L., Danišík, M., Ellero, A., Ottria, G., and Piromallo, C.: Contrasting styles of (U) HP rock exhumation along the Cenozoic Adria-Europe plate boundary (Western Alps, Calabria, Corsica), Geochem. Geophy. Geosy., 16, 1786–1824, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015GC005767, 2015.

Malusà, M. G., Guillot, S., Zhao, L., Paul, A., Solarino, S., Dumont, T., Schwartz, S., Aubert, C., Baccheschi, P., Eva, E., Lu, Y., Lyu, C., Pondrelli, S., Salimbeni, S., Sun, W., and Yuan, H.: The deep structure of the Alps based on the CIFALPS seismic experiment: A synthesis, Geochem. Geophy. Geosy., 22, e2020GC009466, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020GC009466, 2021.

Manzotti, P., Bosse, V., Pitra, P., Robyr, M., Schiavi, F., and Ballèvre, M.: Exhumation rates in the Gran Paradiso Massif (Western Alps) constrained by in situ U–Th–Pb dating of accessory phases (monazite, allanite and xenotime), Contrib. Mineral. Petrol., 173, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00410-018-1452-7, 2018.

Manzotti, P., Schiavi, F., Nosenzo, F., Pitra, P., and Ballèvre, M.: A journey towards the forbidden zone: a new, cold, UHP unit in the Dora-Maira Massif (Western Alps), Contrib. Mineral. Petrol., 177, 59, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00410-022-01923-8, 2022.

Marthaler, M. and Stampfli, G. M.: Les Schistes lustrés à ophiolites de la nappe du Tsaté: Un ancien prisme d'accrétion issu de la marge active apulienne?, Schweizerische mineralogische und petrographische Mitteilungen, 69, 211–216, 1989.

Mazzucchelli, M. L., Burnley, P., Angel, R. J., Morganti, S., Domeneghetti, M. C., Nestola, F., and Alvaro, M.: Elastic geothermobarometry: corrections for the geometry of the host-inclusion system, Geology, 46, 231–234, https://doi.org/10.1130/G39807.1, 2018.

Michard, A., Goffé, B., Chopin, C., and Henry, C.: Did the Western Alps develop through an Oman-type stage? The geotectonic setting of high-pressure metamorphism in two contrasting Tethyan transects, Eclogae Geol. Helv., 89, 43–80, 1996.

Platt, J. P.: Dynamics of orogenic wedges and the uplift of high-pressure metamorphic rocks, Geol. Soc. Am. Bull., 97, 1037–1053, https://doi.org/10.1130/0016-7606(1986)97<1037:DOOWAT>2.0.CO;2, 1986.

Reinecke, T.: Very-high-pressure metamorphism and uplift of coesite-bearing metasediments from the Zermatt-Saas zone, Western Alps. Eur. J. Mineral., 3, 7–17, https://doi.org/10.1127/ejm/3/1/0007, 1991.

Rosenbaum, G. and Lister, G. S.: The Western Alps from the Jurassic to Oligocene: Spatiotemporal Constraints and Evolutionary Reconstructions, Earth Sci. Rev., 69, 281–306, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2004.10.001, 2005.

Scaramuzzo, E., Livio, F. A., Granado, P., Di Capua, A., and Bitonte, R.: Anatomy and kinematic evolution of an ancient passive margin involved into an orogenic wedge (Western Southern Alps, Varese area, Italy and Switzerland), Swiss J. Geosci., 115, 4, https://doi.org/10.1186/s00015-021-00404-7, 2022.

Schmid, S. M., Fügenschuh, B., Kissling, E., and Schuster, R.: Tectonic map and overall architecture of the Alpine orogen, Eclogae Geol. Helv., 97, 93–117, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00015-004-1113-x, 2004.

Schmid, S. M., Kissling, E., Diehl, T., van Hinsbergen, D. J. J., and Molli, G.: Ivrea mantle wedge, arc of the Western Alps, and kinematic evolution of the Alps–Apennines orogenic system, Swiss J. Geosci, 110, 581–612, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00015-016-0237-0, 2017.

Schönig, J., von Eynatten, H., Meinhold, G., and Lünsdorf, N. K.: Diamond and coesite inclusions in detrital garnet of the Saxonian Erzgebirge, Germany, Geology, 47, 715–18, https://doi.org/10.1130/G46253.1, 2019. Schönig, J., von Eynatten, H., Meinhold, G., and Lünsdorf, N. K.: Life-cycle analysis of coesite-bearing garnet, Geological Magazine, 158, 1421–1440, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0016756821000017, 2021.

Smith, D.: Coesite in clinopyroxene in the Caledonides and its implications for geodynamics, Nature, 310, 641–644, https://doi.org/10.1038/310641a0, 1984.

Taguchi, T., Kouketsu, Y., Igami, Y., Kobayashi, T., and Miyake, A.: Hidden intact coesite in deeply subducted rocks, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 558, 116763, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2021.116763, 2021.

Thompson, A. B., Tracy, R. J., Lyttle, P., and Thompson Jr., J. B.: Prograde reaction histories deduced from compositional zonation and mineral inclusions in garnet from the Gassetts schists, Vermont, Am. J. Sci., 277, 1152–1167, https://doi.org/10.2475/ajs.277.9.1152, 1977.

Warr, L. N.: IMA-CNMNC approved mineral symbols, Mineral. Mag., 85, 291–320, https://doi.org/10.1180/mgm.2021.43, 2021.

Zhang, L., Ellis, D. J., and Jiang, W.: Ultrahigh-pressure metamorphism in western Tianshan, China: part I. Evidence from inclusions of coesite pseudomorphs in garnet and from quartz exsolution lamellae in omphacite in eclogites, Am. Mineral., 87, 853–860, https://doi.org/10.2138/am-2002-0707, 2002.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Geological setting

- Methods

- Sample description and mineral chemistry

- Mineral inclusions in garnet

- Metamorphic evolution

- Discussion and implications

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Supplement

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Geological setting

- Methods

- Sample description and mineral chemistry

- Mineral inclusions in garnet

- Metamorphic evolution

- Discussion and implications

- Data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Supplement