the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Fluormacraeite, [(H2O)K]Mn2(Fe2Ti)(PO4)4[OF](H2O)10 ⋅ 4H2O, the first type mineral from the Plößberg pegmatite, Upper Palatinate, Bavaria, Germany

Ian E. Grey

Christian Rewitzer

Rupert Hochleitner

Anthony R. Kampf

Stephanie Boer

William G. Mumme

Nicholas C. Wilson

Cameron J. Davidson

Fluormacraeite, [(H2O)K]Mn2(Fe2Ti)(PO4)4[OF](H2O)10 ⋅ 4H2O, is a new monoclinic member of the paulkerrite group from the Plößberg pegmatite, Upper Palatinate, Bavaria, Germany. It was found in specimens of magnesium-bearing triplite. Associated minerals are spherical blue phosphosiderite, pink-coloured strengite micro-crystals, white fluorapatite globules, light-yellow leucophosphite, black–green rockbridgeite, and reddish-brown cacoxenite. Fluormacraeite occurs as isolated pale-yellow rhombic tablets, flattened on (010) with diameters in the range of 50 to 150 µm and thicknesses on the order of 10 to 30 µm. The crystal forms are {010}, {001}, and {111}. The calculated density for the empirical formula and single-crystal unit-cell volume is 2.39 g cm−3. Optically, fluormacraeite crystals are biaxial (+), with α=1.610(3), β=1.620(3), and γ=1.644(3) (measured in white light). The calculated 2V is 66.5°. The optical orientation is X=b, Y=c, and Z=a. The empirical formula from electron microprobe analyses and structure refinement is A1[K0.14(H2O)0.76]Σ0.90 A2[K0.79(H2O)0.21]Σ1.00 M1(MnMg0.25)Σ2.00 M2+M3(FeAl0.13TiMg0.01)Σ3.00

(PO4)4.00 X[O0.94F0.81(OH)0.25]Σ2.00(H2O)10 ⋅ 3.90H2O.

Fluormacraeite has monoclinic symmetry with space group P21/c and unit-cell parameters a=10.546(2) Å, b=20.655(1) Å, c=12.405(1) Å, β=90.09(1)°, V=2702.1(6) Å3, and Z=4. The crystal structure was refined using synchrotron single-crystal data to wRobs=0.0559 for 5646 reflections with I>3σ(I). Fluormacraeite is isostructural with the paulkerrite-group minerals pleysteinite, macraeite, rewitzerite, hochleitnerite, fluor-rewitzerite, sperlingite, and paulkerrite, with ordering of K and H2O at different A sites (A1 and A2) using the general formula A1A2M12M22M3(PO4)4X2(H2O)10 ⋅ 4H2O. It is the F analogue of macraeite, with OF replacing O(OH) at the X2 sites. The general crystal–chemical properties of the monoclinic paulkerrite-group minerals are compared.

- Article

(5132 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(337 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Fluormacraeite was found in specimens of magnesium-bearing triplite–zwieselite from the Plößberg phosphate pegmatite in the Upper Palatinate, northeast Bavaria. The Plößberg pegmatite is part of the extensive aplitic and pegmatitic igneous intrusions of the northeastern Bavarian pegmatite province. It is located only 18 km from Hagendorf but differs mineralogically from the larger discordant Hagendorf–Pleystein–Waidhaus intrusions in being baryte and beryl bearing (Dill et al., 2011). In the first half of the 20th century, the Plößberg pegmatite was mined for feldspar and quartz at the Lindner Mine, and the mine dumps at the Lindner Quarry have provided a valuable source of beryl, tourmaline, and phosphate minerals for mineralogists and collectors. Dill et al. (2009, 2011) reported Mn-bearing fluorapatite, Mg-bearing triplite–zwieselite, strunzite, beraunite, phosphosiderite, strengite, cacoxenite, autunite, and florencite as the phosphate minerals from the locality. They also described a close association of phosphosiderite and strengite with the titanium-phosphate mineral paulkerrite in specimens from the pegmatite (Dill et al., 2009).

We have recently characterized five new monoclinic members of the paulkerrite group from the nearby Hagendorf Süd pegmatite. They conform to the general formula A1A2M12M22M3(PO4)4X2(H2O)10 ⋅ 4H2O (Grey et al., 2023a), with A1A2 = (H2O)K and with M1 (M22M3) and X2 = Mn, Al3, F2 in pleysteinite (Rewitzer et al., 2024a); Mn, Al2Ti, O(OH) in rewitzerite (Grey et al., 2023b); Mn, Al2Ti, OF in fluor-rewitzerite (Hochleitner et al., 2024a); Mn, Ti2Fe, O2 in hochleitnerite (Rewitzer et al., 2024a); and (MnFe, Al2Ti, O(OH) in sperlingite (Rewitzer et al., 2024b). The crystals of all five minerals were found on the walls of vugs in altered zwieselite–triplite, and on this basis, a systematic scanning electron microscopy/energy-dispersive spectrometry study was initiated on zwieselite–triplite specimens in museum collections and the private collection of one of the authors (CR). This led to the finding of crystals in a specimen collected from the mine dumps of the Lindner Mine, which corresponded compositionally to macraeite, [(H2O)K]Mn2(Fe2Ti)(PO4)4[O(OH)](H2O)10 ⋅ 4H2O, but with a higher F content. Electron microprobe analyses subsequently showed the mineral to be the F analogue of macraeite. The mineral and its name have been approved by the International Mineralogical Association (IMA) Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification (CNMNC), IMA-2024-054.

The holotype specimen is housed in the mineralogical collections of the Mineralogical State Collection, Munich, registration number MSM38573. A co-type specimen used for the optics and the Raman spectrum is housed in the mineralogical collections of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, catalogue number 76422.

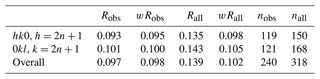

The complete locality for fluormacraeite is the Plößberg phosphate pegmatite, located 15 km north–northeast of Hagendorf in Tirschenreuth district, Upper Palatinate, Bavaria, Germany. Fluormacraeite is the first type mineral for the locality. The pegmatite is embedded in Moldanubian biotite–gneisses. Tabular pegmatitic bodies up to a thickness of 2 m are embedded in these gneisses, with a significant tourmalinization at the contact (Dill et al., 2011). Alkaline feldspar and quartz occur in blocky intergrowths, sometimes with graphic texture. Beryl in prismatic crystals up to 10 cm is embedded in the quartz. The K–feldspar shows perthitic intergrowth with albite. Biotite is found at the contact with the wall rocks in particular, where it is mainly altered to chlorite. The main primary phosphate mineral is a magnesian member of the triplite–zwieselite series, occurring in patches up to 20 cm. A microprobe analysis of the triplite gave the composition Mn0.89Fe0.68Mg0.43(PO4)F0.87(OH)0.13. The triplite is host to crystals of the new mineral, grown on fissures in the otherwise very fresh and unaltered mineral (Fig. 1). Associated minerals are spherical blue phosphosiderite, pink-coloured strengite micro-crystals, white fluorapatite globules, light-yellow leucophosphite, black–green rockbridgeite, and reddish-brown cacoxenite.

Figure 1Pale-yellow crystals of fluormacraeite on yellow–brown magnesium-bearing triplite. Associated minerals are white fluorapatite and reddish-brown cacoxenite. FOV 0.39 mm. Photo by Christian Rewitzer.

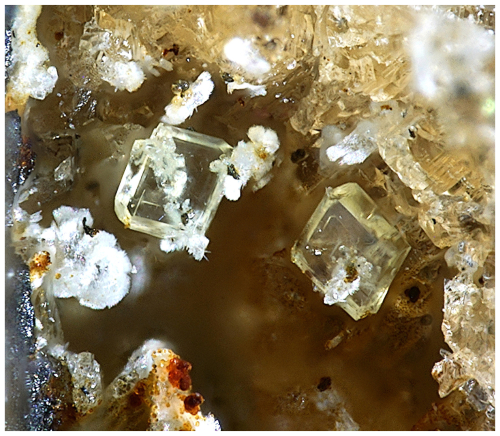

Figure 2A crystal of fluormacraeite photographed under crossed polarizers, showing interference colour changes due to [001] twinning and sector zoning across sector boundaries, which is shown by the dotted line for one of the boundaries. Photo by Tony Kampf.

Fluormacraeite occurs as isolated pale-yellow rhombic tablets, flattened on (010) with diameters in the range of 50 to 150 µm and thicknesses on the order of 10 to 30 µm (Fig. 1). The crystal forms are {010}, {001}, and {111}. The calculated density for the empirical formula and single-crystal unit-cell volume is 2.39 g cm−3.

Optically, fluormacraeite crystals are biaxial (+), with α=1.610(3), β=1.620(3), and γ=1.644(3) (measured in white light). The calculated 2V is 66.5°. The optical orientation is X=b, Y=c, and Z=a. When viewed under crossed polarizers, the fluormacraeite crystals showed colour variations due to sector twinning, as shown in Fig. 2. The [001] twinning was particularly evident when the crystals were rotated. The Gladstone–Dale compatibility index (Mandarino, 1981) is 0.0083 (superior) based on the empirical formula and the calculated density.

Crystals of fluormacraeite were analysed using wavelength-dispersive spectrometry on a JEOL JXA 8530F Hyperprobe operated at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV and a beam current of 2 nA. The beam was de-focused to 4 µm. Paulkerrite-group minerals have high water content and dehydrate readily in the vacuum of the microprobe, giving variable analysis totals. To minimize this effect, a cold stage cooled to liquid nitrogen temperature was employed in the microprobe, and the specimen was pre-cooled under dry nitrogen prior to introduction into the microprobe.

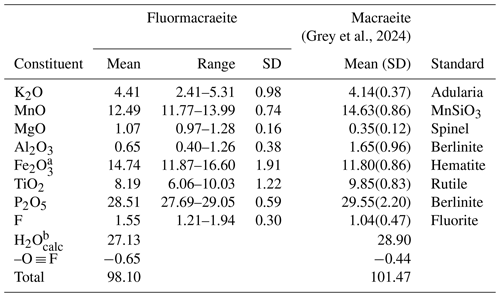

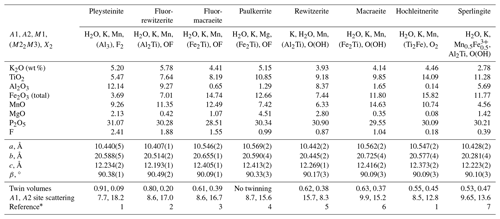

Analytical results (the average of eight analyses on two crystals) are given in Table 1, where they are compared with the analyses for macraeite (Grey et al., 2024). There was insufficient material for the direct determination of H2O, the presence of which is confirmed by Raman spectroscopy, so it was based upon the crystal structure, with 15 H2O per 4 P. The calculated water content was included in the in-house matrix correction procedure. Fluormacraeite has a much higher Fe2O3 content than macraeite and also has higher MgO and F, with lower MnO, Al2O3, and TiO2. The fluormacraeite analyses show a strong negative correlation between Fe2O3 and TiO2 (R2=0.82) and a weak positive correlation between K and TiO2 (R2=0.48). No clear correlation was found between F and the different M constituents.

The atomic fractions, normalized to 9(), are

K0.93Mn1.75Mg0.26Al0.13FeTiP4.00F0.81O32.05H30.

The corresponding empirical formula in structural form is

A1[K0.14(H2O)0.76]Σ0.90

A2[K0.79(H2O)0.21]Σ1.00

M1(MnMg0.25)Σ2.00 M2+M3(FeAl0.13TiMg0.01)Σ3.00

(PO4)4.00 X[O0.94F0.81(OH)0.25]Σ2.00(H2O)10 ⋅ 3.90H2O,

where the M2 and M3 sites are grouped based on the site-total-charge procedure (Bosi et al., 2019; Grey et al., 2023a). The simplified formula is

[(H2O),K][K,(H2O)] (Mn2+,Mg)2(Fe3+,Al,Ti4+)3(PO4)4

(O,F)2(H2O)10 ⋅ 4H2O.

The ideal end-member formula based on the dominant constituents at each site is

[(H2O)K]Mn2Fe2Ti(PO4)4(OF)(H2O)10 ⋅ 4H2O, which requires K2O 4.74, MnO 14.28, Fe2O3 16.07, TiO2 8.04, P2O5 28.58, H2O 27.18, F 1.91, -O ≡ F -0.80, total 100 wt %.

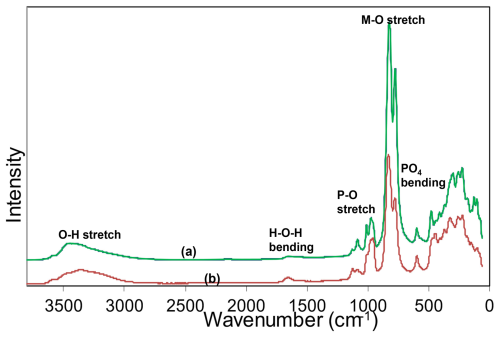

Raman spectroscopy was conducted on a Horiba XploRA PLUS spectrometer using a 532 nm diode laser, 100 µm slit, and 1800 g mm−1 diffraction grating with a 100 × (0.9 NA) objective. The spectrometer was calibrated using the 520.7 cm−1 band of silicon. The sample was susceptible to thermal damage at high laser power, so the spectrum was recorded at a laser power of 4 mW. The sample was examined after the spectrum was recorded to verify that no thermal damage had occurred. The spectrum is compared with that of macraeite in Fig. 3. The spectra are very similar. The O–H stretch region has a broad band centred at 3455 cm−1, with a shoulder at 3350 cm−1. The H–O–H bending mode region for water has a band at 1650 cm−1. The P–O stretching region has a band at 975 cm−1, with shoulders at 955 and 1010 cm−1 corresponding to symmetric stretching modes, and two weaker bands at 1085 and 1130 cm−1 corresponding to antisymmetric stretching modes. Bending modes of the (PO4)3− groups are manifested by bands centred at 595 and 480 cm−1. Peaks at lower wavenumbers are related to lattice vibrations. An intense pair of bands at 775 and 825 cm−1 can be assigned to metal–oxygen stretch vibrations for short M2–O bonds that occur in linear trimers of the corner-connected octahedra M2–M3–M2 in the structure. The potassium titanyl phosphate, KTiOPO4, has chains of corner-connected octahedra with short (1.81–1.83 Å) Ti–O bonds, and the Raman spectrum has an intense band at 770 cm−1 that has been assigned to the symmetric Ti–O stretching vibration (Tu et al., 1996). Strong Raman bands in the range of 800 to 900 cm−1 have been reported and assigned to Ti–O stretch vibrations for several potassium titanium oxides, which have corner-connected TiO6 octahedra involving short (∼ 1.8 Å) Ti–O bonds (Bamberger et al., 1990). The M2 sites in fluormacraeite similarly have the M2 atom displaced from the centre of the octahedra towards the corner-sharing anion with the M3-centred octahedron, giving short (1.89 Å) M2–X bonds.

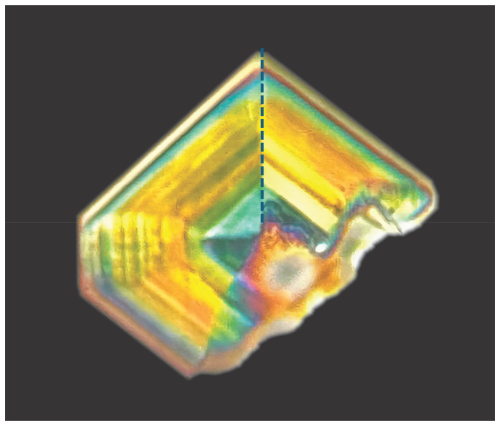

Table 4Atom coordinates, equivalent isotropic displacement parameters (Å2), and bond-valence sums (BVSs, in valence units) for fluormacraeite.

* Site scattering (electrons) – M1a 22.90, M1b 23.42, M2a 23.35, M2b 23.06, M3a 23.35, M3b 23.09. Site occupancy – A1 = 0.132(7)K + 0.768H2O, A2 = 0.794(6)K + 0.206H2O.

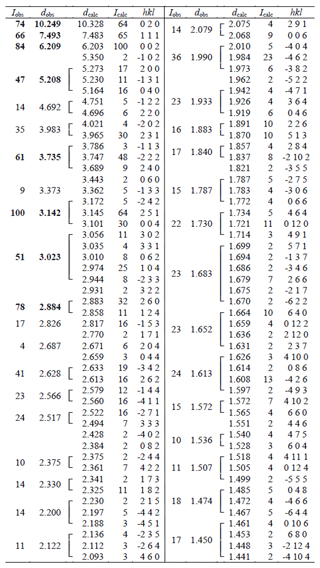

6.1 X-ray powder diffraction

Powder X-ray studies were done using a Rigaku R-Axis Rapid II curved imaging plate micro-diffractometer with monochromatized MoKα radiation. A Gandolfi-like motion on the φ and ω axes was used to randomize the sample. Observed d values and intensities were derived by profile fitting using JADE Pro software (Materials Data, Inc.). Data (in Å for MoKα) are given in Table 2. The refined monoclinic unit-cell parameters (space group P21/c (no. 14)) are a=10.531(17) Å, b=20.652(18) Å, c=12.408(17) Å, β=90.1(2)°, V=2699(6) Å3, and Z=4.

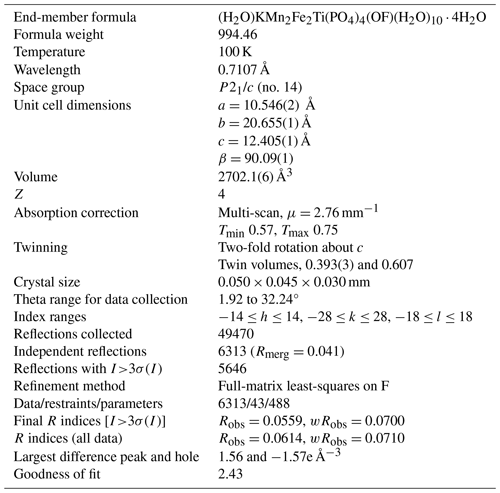

6.2 Synchrotron single-crystal diffraction

A crystal measuring 0.050 × 0.045 × 0.030 mm was used for data collection at the Australian Synchrotron microfocus beamline MX2 (Aragao et al., 2018). Intensity data were collected using a Dectris Eiger 16M detector and monochromatic radiation with a wavelength of 0.7107 Å. The crystal was maintained at 100 K in an open-flow nitrogen cryostream during data collection. The diffraction data were collected using a single 36 s sweep of 360° rotation around phi. The resulting dataset consists of 3600 individual images, with the approximate phi angle of each image being 0.1°. The raw intensity dataset was processed using the XDS software to produce data files that were analysed using SHELXT (Sheldrick, 2015), WinGX (Farrugia, 1999), and JANA2006 (Petříček et al., 2014). Refined unit-cell parameters and other data collection details are given in Table 3.

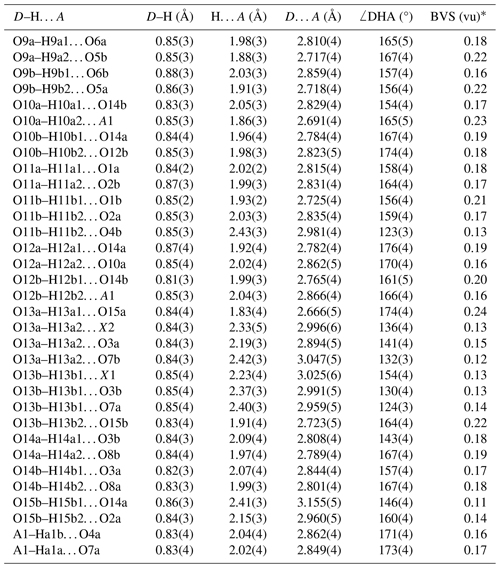

A structural model for fluormacraeite was obtained in space group P21/c using SHELXT. The model had the same atomic arrangement as macraeite, so the metal atom and anion coordinates for the macraeite structure were used as a starting model to maintain the same atom labelling. [001] twinning by pseudo-merohedry, which was indicated in TWINROTMAT within WinGX, was implemented. Based on the close relationship to macraeite, the Mn scattering curve was used for the M1 sites, and the Fe scattering curve was used for the M2 and M3 sites; the occupancies were refined in each case. A mixture of K and O (for H2O) was assigned to the A1 and A2 sites. Refinement of the ratios gave a combined K content lower than the mean EMP value, suggesting the presence of vacancies, as previously found for paulkerrite-group minerals (Rewitzer et al., 2024a). Vacancies were included at A1, and the (fixed) number was incrementally adjusted to obtain a closer match to the EMP analyses for K. After refinement of all atoms using anisotropic displacement parameters in JANA2006, difference-Fourier maps were used to locate H atoms. The H atoms were refined with soft restraints (O–H = 0.85(1) Å and H–O–H = 109.47(1)°) and with an overall isotropic displacement parameter. The refinement converged at Robs=0.056 for 5646 reflections with I>3σ(I). Further details of the data collection and refinement are given in Table 3. The refined atom coordinates, equivalent isotropic displacement parameters, and bond-valence sum (BVS) values (parameters from Gagné and Hawthorne, 2015) are reported in Table 4. Selected interatomic distances are reported in Table 5, and the H bonding is given in Table 6. Also included in Table 6 are the BVS contributions of the H atoms to the acceptor atoms. These were calculated from the O…O distances (D…A in Table 6) using the function and parameters reported by Ferraris and Ivaldi (1988). The use of O…O distances in the calculation of the H BVS contributions is more reliable than using the O–H and H…O distances (Ferraris and Ivaldi, 1988) because the H positions determined from X-ray intensity data give anomalously short O–H distances (Huminicki and Hawthorne, 2002).

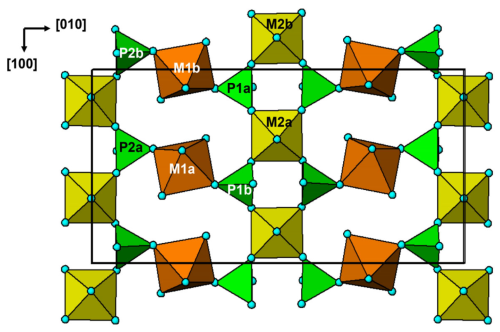

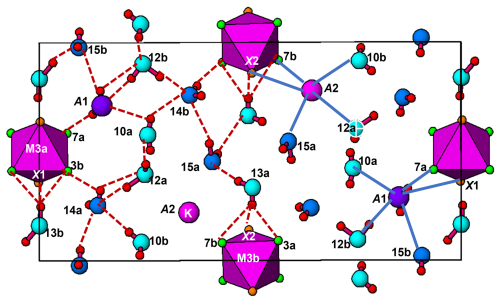

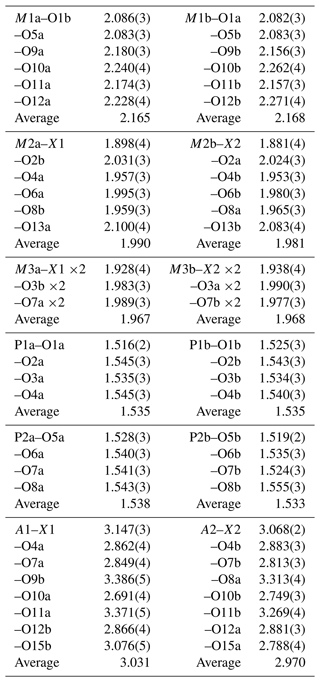

Fluormacraeite is isostructural with monoclinic paulkerrite-group minerals of the general composition A1A2M12M22M3(PO4)4X2(H2O)10 ⋅ 4H2O (Grey et al., 2023a). The structure is based on an alternation of two types of layers parallel to (001), as shown in Figs. 4 and 5. Hetero-polyhedral layers located at and (Fig. 4) have the composition M12M22M3(PO4)4(OF)(H2O)10 and are built from [100] kröhnkite-type chains (Hawthorne, 1985) of four-member rings of corner-connected PO4 tetrahedra and M2O4X(H2O) octahedra. Each tetrahedron also shares a corner with M1O2(H2O)4 octahedra along [010]. The corner-shared linkages form eight-member rings of alternating octahedra and tetrahedra. Layers, as shown in Fig. 4, are interconnected into an open 3D framework by corner sharing of the M2O4X(H2O) octahedra with M3O4X2 octahedra located at z=0 and (Fig. 5). In addition to the M3O4X2 octahedra, the layers at z = 0 and contain the zeolitic H2O groups O14 and O15, as well as H2O groups coordinated with M1 cations (O9 to O12) and with M2 cations (O13). Extensive intra-plane H bonding occurs, as shown in Fig. 5 and Table 6. The H bonding obtained for fluormacraeite is the same as is obtained for macraeite (Grey et al., 2024) and fluor-rewitzerite (Hochleitner et al., 2024a). Noteworthy are the trifurcated bonds associated with O13a and O13b. These water molecules each have H bonds with three acceptor anions that form a face of the M3-centred octahedra (X2–O3a–O7b and X1–O3b–O7a, respectively), shown in Fig. 5. The water molecule O11b has bifurcated H bonds to an octahedral edge, O2a–O4b, of the M2b-centred octahedron. According to the Libowitzky (1999) classification of H bonds, only those associated with O10a…A1 and O13a…O15a are considered strong bonds, with O…O < 2.7 Å. This is reflected in the BVS contribution from H values of 0.23 and 0.24 vu for these bonds given in Table 6, while the weakest bond, O15b–H15b1…O14a, has a H BVS contribution to the acceptor atom of only 0.11 vu.

Fluormacraeite is the fluorine analogue of macraeite, with OF replacing O(OH) at the X sites. Dill et al. (2009) gave the composition of the mineral they described as paulkerrite as

(H2O,K)2(Mg0.36Mn0.64)2Fe2Ti(PO4)4(O,F)2 ⋅ 14H2O. With Mn dominant over Mg at the M1 site, their mineral cannot be paulkerrite, as they reported. They did not give K or F analyses, but if their mineral contains more than 0.5 K pfu, then it would correspond to fluormacraeite.

The crystal-chemical properties of fluormacraeite are compared with those for other monoclinic paulkerrite-group minerals in Table 7. As discussed by Hochleitner et al. (2024a), the magnitude of the monoclinic distortion correlates positively with the difference in scattering between the A1 and A2 sites (which measures the extent of the ordering of K and H2O at the A sites). A plot of β-90 vs. the A-site scattering difference gave R2=0.70 for a linear plot. The results in Table 7 show that there is also a correlation between the magnitude of monoclinic distortion and the extent of [001] twinning, where the minerals with the greatest monoclinicity are either untwinned or have a dominant twin individual, and decreasing monoclinicity is associated with a decreasing difference in the twin volumes. This is consistent with [001] twinning by pseudo-merohedry, where the higher symmetry corresponds to an orthorhombic cell with space group Pbca. Orthorhombic symmetry was reported for benyacarite, the first paulkerrite-group mineral to have its structure determined, with the cell parameters a=10.561(5), b=20.585(8), and c=12.516(2) Å (Demartin et al. (1993). The authors obtained an excellent refinement (Rw=0.040) in Pbca. However an indication that benyacarite is only pseudo-orthorhombic is suggested by the high reported anisotropic displacement parameters (ADPs) for O15 (Unn=0.05–0.06 Å2). As discussed elsewhere (Rewitzer et al., 2024a), in going from a pseudo-orthorhombic Pbca model to a monoclinic P21/c model for paulkerrite-group minerals, the largest atomic displacements occur for the O15 water molecules, so the high ADPs for O15 in a Pbca refinement could reflect local monoclinic symmetry.

Table 7Crystal–chemical trends in monoclinic paulkerrite-group minerals; the ideal formula is A1A2M12M22M3(PO4)4X2(H2O)10 ⋅ 4H2O.

* (1) Rewitzer et al. (2024a), (2) Hochleitner et al. (2024a), (3) this study, (4) Grey et al. (2023a), (5) Grey et al. (2023b), (6) Grey et al. (2024), (7) Rewitzer et al. (2024b).

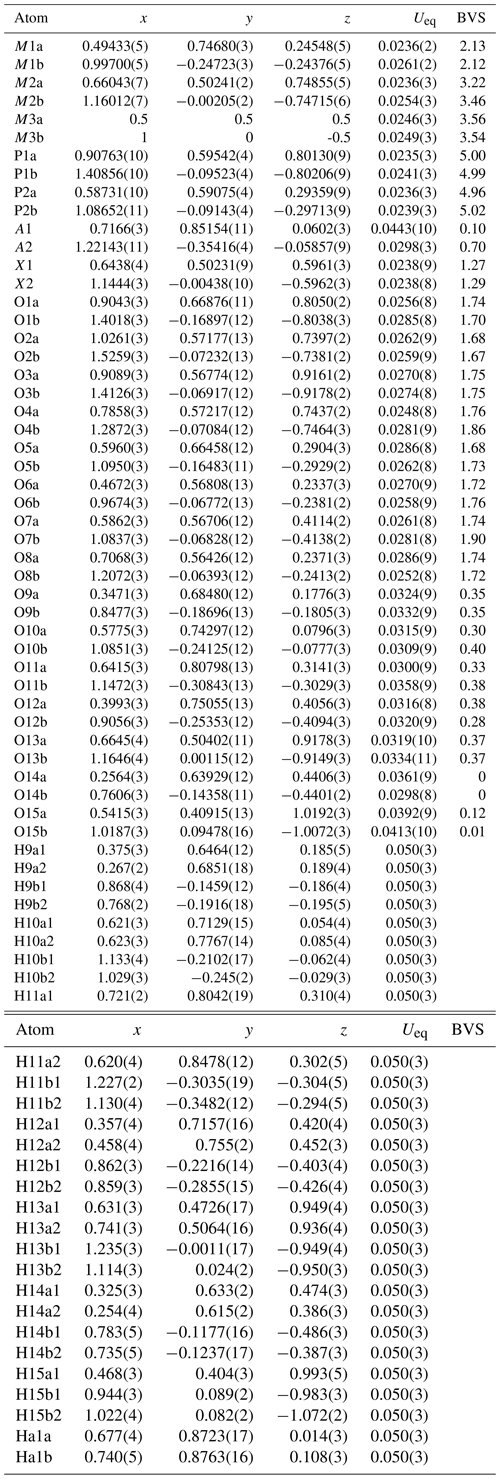

The combination of high diffraction spot mosaicity, [001] twinning, and sector zoning can make it difficult to distinguish between monoclinic and orthorhombic symmetry for paulkerrite-group minerals with small monoclinicity, particularly when the intensity data collections are made with laboratory diffractometers for which the diffraction is collected from relatively large areas (hundreds of µm). In the characterization of the new paulkerrite-group minerals pleysteinite and hochleitnerite, the diffraction datasets were originally collected using a laboratory diffractometer with a beam diameter of ∼ 150 µm, and in both cases the data processing gave orthorhombic cells. However, subsequent data collection made on both minerals using a synchrotron microfocus beam (10×20 µm) showed them to have monoclinic symmetry, P21/c (Rewitzer et al., 2024b), albeit with small monoclinicity (β=90.09(3)° for hochleitnerite). The clearest indication of the lowering of symmetry from orthorhombic, Pbca, to monoclinic, P21/c, is the presence of the reflections hk0, , and 0kl, , which are forbidden in Pbca due to the presence of the a and b glide planes. For fluormacraeite, the partial R factors for these classes of reflection are given in Table 8. It can be seen that 75 % of the reflections forbidden in Pbca have observed intensities of I>3σ(I) and that a good fit was obtained to the reflections with weighted R factors of 0.10, giving unambiguous support to the monoclinic symmetry.

An example of a paulkerrite-group mineral where only a pseudo-orthorhombic Pbca refinement of the average structure was possible is hydroxylbenyacarite (H2O)2Mn2(Ti2Fe)(PO4)4[O(OH)](H2O)10 ⋅ 4H2O (Hochleitner et al., 2024b). Processing of laboratory X-ray intensity data for this mineral gave an orthorhombic cell with the parameters a=10.5500(3), b=20.7248(5), and c=12.5023(3) Å. The generation of simulated precession images from the data, however, showed the diffuse reflections hk0, , and 0kl, , inconsistent with the space group Pbca. Reprocessing of the data with forced monoclinic symmetry gave the parameters a=10.5467(3), b=20.7222(5), c=12.5031(3) Å, and β = 90.068(2)°. From the lengths of the diffuse forbidden reflections, the monoclinic symmetry is limited to domains with sizes on the scale of the unit cell, 1 to 2 nm. A refinement in P21/c caused problems, with numerous non-positive ADPs and unrealistically wide ranges of P–O distances. In contrast, refinement of the average structure in Pbca gave reasonable P–O distances and only two marginally non-positive ADPs. It is likely that all paulkerrite-group minerals have monoclinic symmetry, at least at the local level, in domains that become smaller with a decrease in monoclinicity.

Returning to the consideration of Table 7, it is seen that compositionally, the highest monoclinicity is associated with high F and Al, but there is considerable scatter. The only strong element–element correlations are negative correlations between Ti and F (R2=0.9) and Al and Fe (R2=0.9). There is a moderate positive correlation of Ti with Fe (R2=0.6). It is interesting that the positive Ti–Fe correlation between the different minerals in Table 7 is counter to the negative Ti–Fe correlation found for the different analyses of fluormacraeite given in Sect. 4. Further discussion of crystal–chemical trends in monoclinic paulkerrite-group minerals is given by Hochleitner et al. (2024a).

Crystallographic data for fluormacraeite are available in the Supplement.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/ejm-37-169-2025-supplement.

IEG oversaw the research and wrote the paper, CR field-collected the specimen, RH and CR obtained preliminary EDS analyses, and CR obtained optical images of the specimen. WGM assisted in the diffraction data analysis; ARK measured the optical properties, Raman spectrum, PXRD, and crystal morphology; SB collected and processed the single-crystal diffraction data; NCW performed the site assignment analysis; and CJD prepared the specimens for electron microprobe analysis.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

This research was undertaken in part using the MX2 beamline at the Australian Synchrotron, a part of ANSTO, and made use of the Australian Cancer Research detector.

This research has been supported by ARC (grant no. LE130100087).

This paper was edited by Cristiano Ferraris and reviewed by Ferraris Giovanni and one anonymous referee.

Aragao, D., Aishima, J., Cherukuvada, H., Clarken, R., Clift, M., Cowieson, N. P., Ericsson, D. J., Gee, C. L., Macedo, S., Mudie, N., Panjikar, S., Price, J. R., Riboldi-Tunnicliffe, A., Rostan, R., Williamson, R., and Caradoc-Davies, T. T.: MX2: a high-flux undulator microfocus beamline serving both the chemical and macromolecular crystallography communities at the Australian Synchrotron, J. Synchr. Radiat., 25, 885–891, 2018.

Bamberger, C. E., Begun, G. M., and MacDougall, C. S.: Raman spectroscopy of potassium titanates: Their synthesis, hydrolytic reactions and thermal stability, Appl. Spectrosc., 44, 31–37, 1990.

Bosi, F., Biagioni, C., and Oberti, R.: On the chemical identification and classification of minerals, Minerals, 9, 591, https://doi.org/10.3390/min9100591, 2019.

Demartin, F., Pilati, T., Gay, H. D., and Gramaccioli, C. M.: The crystal structure of a mineral related to paulkerrite, Z. Kristallogr., 208, 57–71, 1993.

Dill, H. G., Weber, B., and Kollegen, H.: “Angelardite” – eine Verwachsung von Eisen- und Titanphosphat, Ein nueuer Fund von Paulkerrit im Pegmatit von Plößberg/Oberpfalz, Geol. Bl. NO-Bayern, 59, 87–94, 2009.

Dill, H. G., Weber, B., and Botz, R.: The baryte-bearing beryl-phosphate pegmatite Plößberg – a missing link between pegmatite and vein-type barium mineralization in NE Bavaria, Germany, Chem. Erde-Geochem., 71, 377–387, 2011.

Farrugia, L. J.: WinGX suite for small-molecule single-crystal crystallography, J. Appl. Crystallogr., 32, 837–838, 1999.

Ferraris, G. and Ivaldi, G.: Bond valence vs. bond length in O…O hydrogen bonds, Acta Crystallogr. B,44, 341–344, 1988.

Gagné, O. C. and Hawthorne, F. C.: Comprehensive derivation of bond-valence parameters for ion pairs involving oxygen, Acta Crystallogr. B, 71, 562–578, 2015.

Grey, I. E., Boer, S., MacRae, C. M., Wilson, N. C., Mumme, W. G., and Bosi, F.: Crystal chemistry of type paulkerrite and establishment of the paulkerrite group nomenclature, Eur. J. Mineral., 35, 909–919, https://doi.org/10.5194/ejm-35-909-2023, 2023a.

Grey, I. E., Hochleitner, R., Kampf, A. R., Boer, S., MacRae, C. M., Mumme, W. G., and Keck, E.: Rewitzerite, [K(H2O)]Mn2(Al2Ti)(PO4)4[O(OH)](H2O)10 ⋅ 4H2O, a new monoclinic paulkerrite-group mineral, from the Hagendorf Süd pegmatite, Oberpfalz, Bavaria, Germany, Mineral. Mag., 87, 830–838, 2023b.

Grey, I. E., Rewitzer, C., Hochleitner, R., Kampf, A. R., Boer, S., Mumme, W. G., and Wilson, N. C.: Macraeite, [(H2O)K]Mn2(Fe2Ti)(PO4)4[O(OH)](H2O)10 ⋅ 4H2O, a new monoclinic paulkerrite-group mineral, from the Cubos–Mesquitela–Mangualde pegmatite, Portugal, Eur. J. Mineral., 36, 267–278, https://doi.org/10.5194/ejm-36-267-2024, 2024.

Hawthorne, F. C.: Towards a structural classification of minerals: The VIMIVT2Φn minerals, Am. Mineral., 70, 455–473, 1985.

Hochleitner, R., Grey, I. E., Kampf, A. R., Boer, S., MacRae, C. M., Mumme, W. G., and Wilson, N. C.: Fluor-rewitzerite, [(H2O)K]Mn2(Al2Ti)(PO4)4[OF](H2O)10 ⋅ 4H2O, a new paulkerrite-group mineral, from the Hagendorf Süd pegmatite, Oberpfalz, Bavaria, Germany, Eur. J. Mineral., 36, 541–554, https://doi.org/10.5194/ejm-36-541-2024, 2024a.

Hochleitner, R., Rewitzer, C., Grey, I. E., Kampf, A. R., MacRae, C. M., Gable, R. W., and Mumme, W.G.: Hydroxylbenyacarite, (H2O)2Mn2(Ti2Fe)(PO4)4[O(OH)](H2O)10 ⋅ 4H2O, a new paulkerrite-group mineral from the El Criollo mine, Cordoba province, Argentina, Mineral. Mag., 88, 327–334, 2024b.

Huminicki, D. M. C. and Hawthorne, F. C.: Hydrogen bonding in the crystal structure of seamanite, Can. Mineral., 40, 923–928, 2002.

Libowitzky, E.: Correlation of O-H stretching frequencies and O-H…O hydrogen bond lengths in minerals, Monatsch. Chemie, 130, 1047–1059, 1999.

Mandarino, J. A.: The Gladstone-Dale relationship: Part IV. The compatibility concept and its application, Can. Mineral., 19, 441–450, 1981.

Petříček, V., Dušek, M., and Palatinus, L.: Crystallographic Computing System JANA2006: General features, Z. Kristallogr., 229, 345–352, 2014.

Rewitzer, C., Hochleitner, R., Grey, I. E., MacRae, C. M., Mumme, W. G., Boer, S., Kampf, A. R., and Gable, R. W.: Monoclinic pleysteinite and hochleitnerite from the Hagendorf Süd pegmatite, Synchrotron microfocus diffraction studies on paulkerrite-group minerals, Can. J. Mineral. Petrol., 62, 513–527, 2024a.

Rewitzer, C., Hochleitner, R., Grey, I. E., Kampf, A. R., Boer, S., MacRae, C. M., Mumme, W. G., Wilson, N. C., and Davidson, C.: Sperlingite, [(H2O)K](Mn2+Fe3+)(Al2Ti)(PO4)4[O(OH)][(H2O)9(OH)] ⋅ 4H2O, a new paulkerrite-group mineral, from the Hagendorf Süd pegmatite, Oberpfalz, Bavaria, Germany, Mineral. Mag., 88, 576–584, 2024b.

Sheldrick, G. M.: Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL, Acta Crystallogr. C, 71, 3–8, 2015.

Tu, C.-S., Guo, A. R., Tao, R., Katiyar, R. S., Guo, R., and Bhalla, A. S.: Temperature dependent Raman scattering in KTiOPO4 and KTiOAsO4 single crystals, J. Appl. Phys., 79, 3235–3240, 1996.